Berlinde De Bruyckere

Pierre Huyghe

10 FAVORITE ARTISTS - in progress

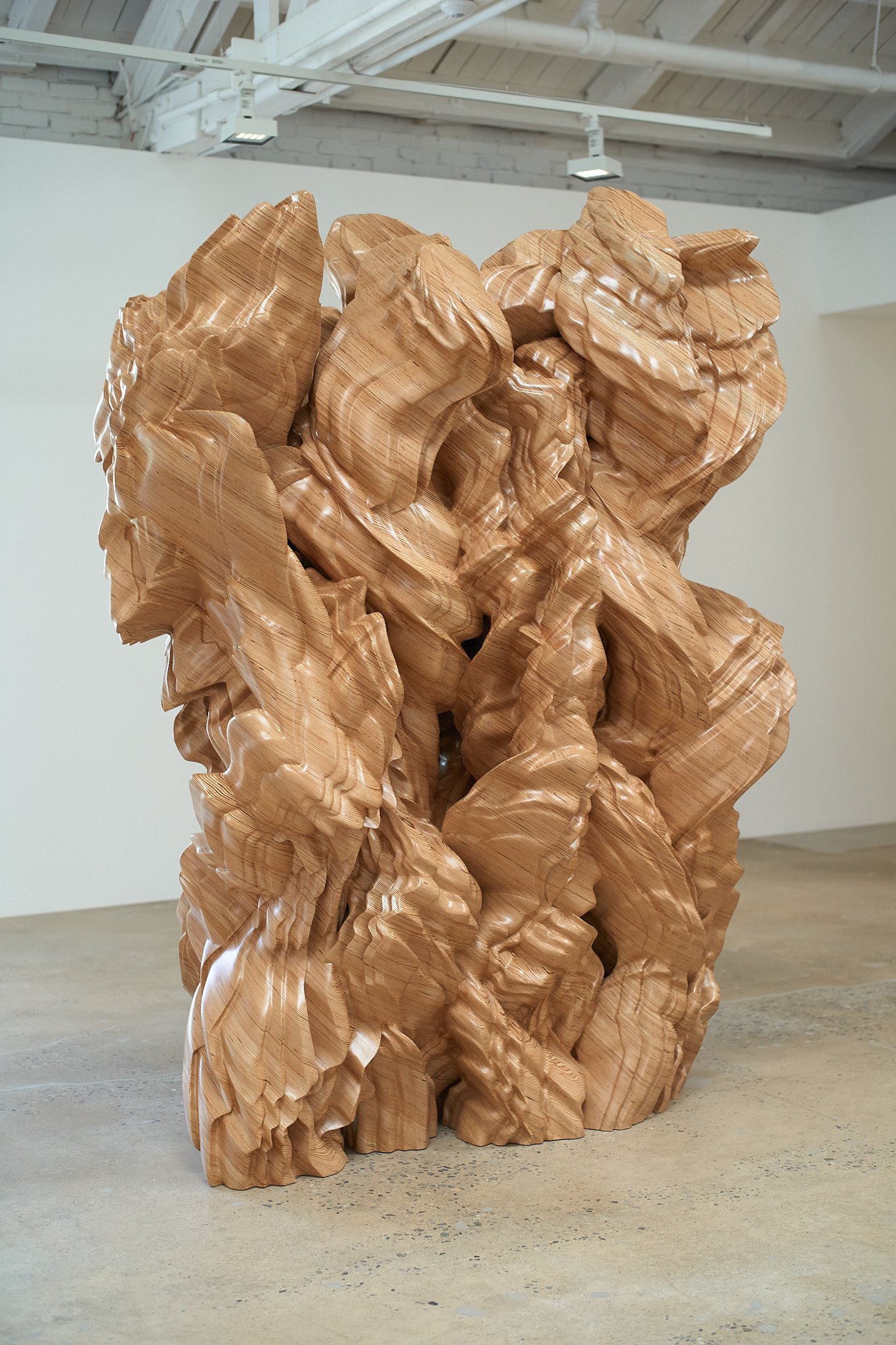

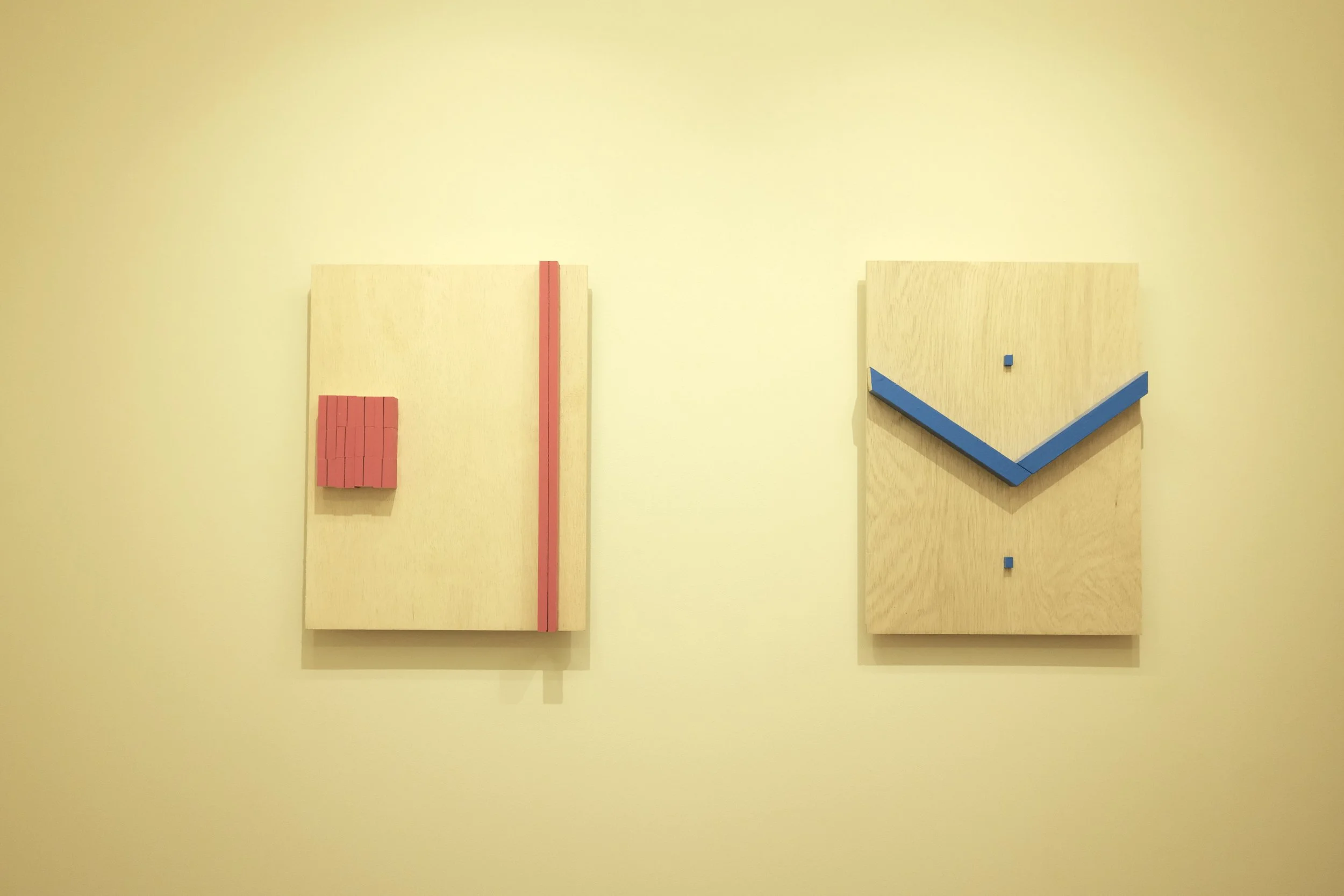

CADAN YURAKUCHO 有楽町

KO+GEI prologue

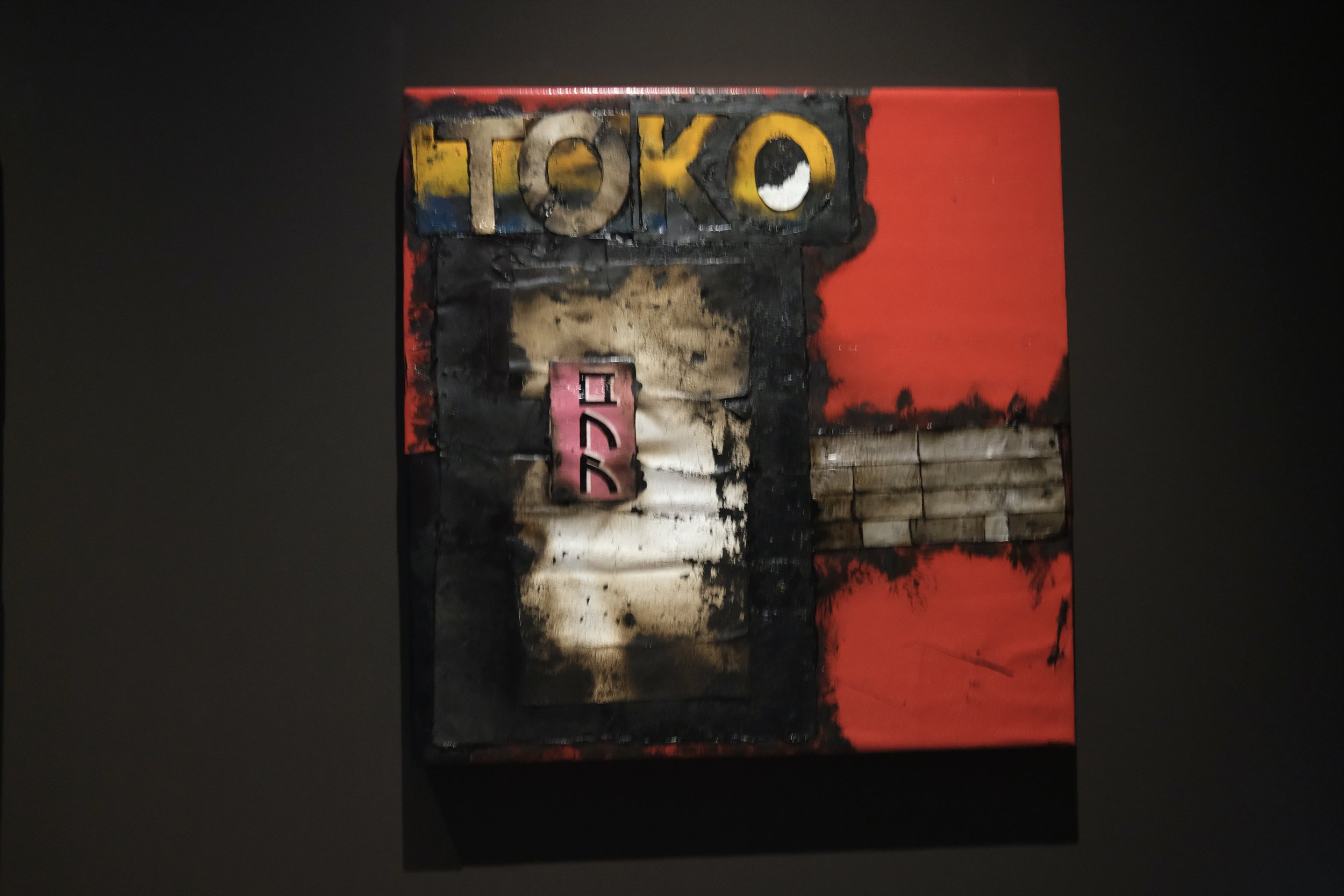

Theaster Gates: Afro-Mingei

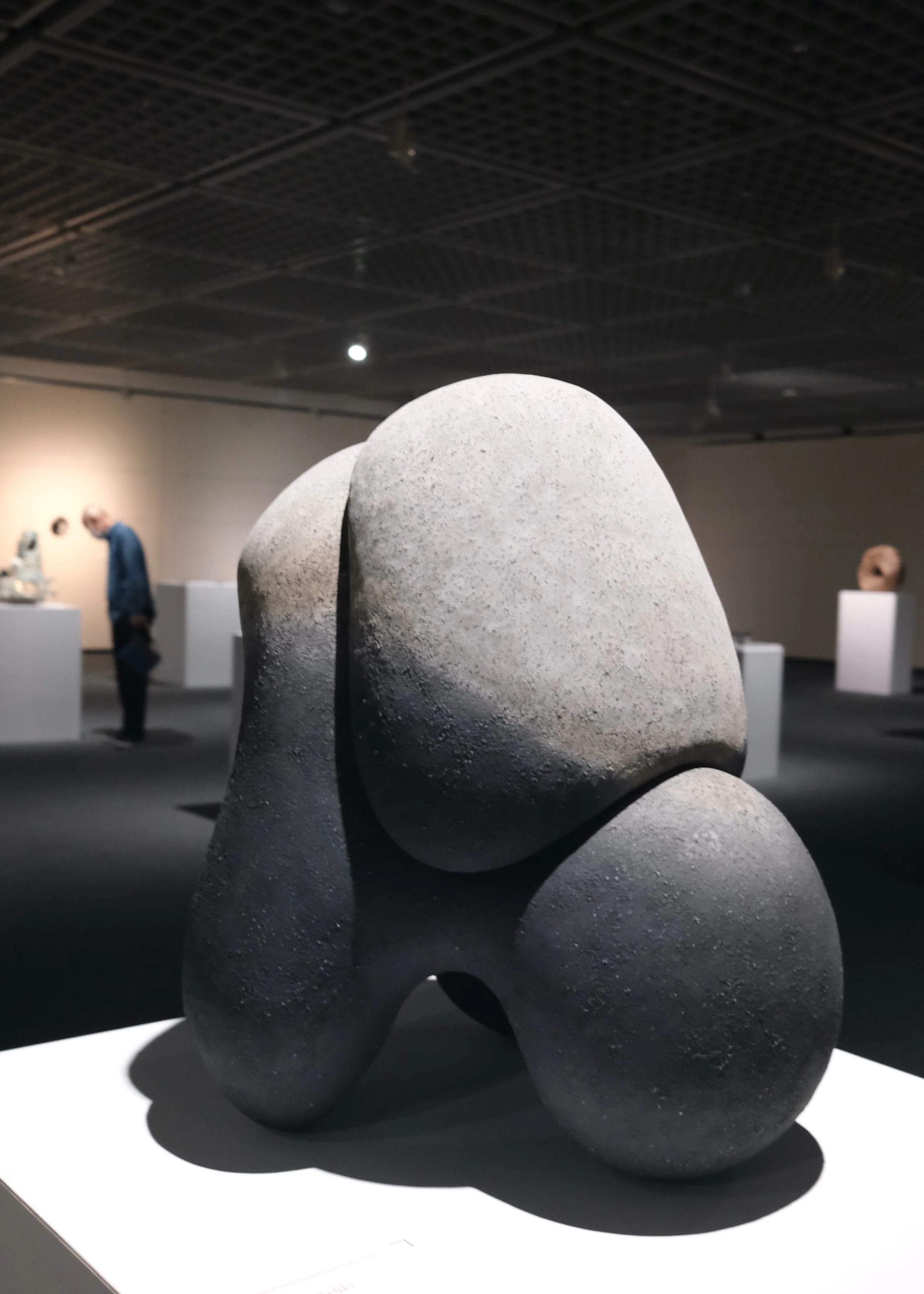

Jose Dàvila - River Stones

Venezia Biennale - Giardini - FRANCE

Betye Saar: Drifting Toward Twilight

WHAT WILL YOU GIVE? Veronica Fernandez Tidawhitney Lek

Coco Young - Passage

Clare Woods - I Blame Nature

Elaine Stocki

Ursula magazine - artists Fabien Giraud and Raphael Siboni in conversation with Anne Stenne about possible futures and the influence of Pierre Huyghe

FG: I think a good work is a work that doesn't know its audience. Upon its creation, it doesn't yet know what its audience is, because otherwise it's just communication. Communication is about the transfer of information between two pre-constituted subjects. But the question mark is what I'm obsessed with — and I think Pierre is also. You don't know the identity of the audience or the viewer. And I think that's crucial, not to presuppose. Otherwise, you do bad work.

AS: I agree with you. The work should not be addressed intentionally to an audience as such. It should be indifferent. To push the idea further, it can also exist independent of the presence of the viewer, which is something essential in Pierre's work. He often says, "I'm not exhibiting some thing to someone. I'm exhibiting someone to something.”

FG: It's very difficult to presuppose what the human really is. The only definition of the human I can come up with is that it's something always in the process of transformation of de-identifying itself to become itself.

AS: The human is an escape route.

ELYSIUM - a visual history of angelology

A disservice, a slander, a libel-for angelology as properly constituted has nothing to do with Touched by an Angel or Hummel figurines. Angelology, rather, is the discipline that probes the ecstasies of transcendence, the ineffable nature of meaning that permeates reality, in a space with which words themselves can't fully grapple. Just because angelology reduces us to the wooliest of superlatives -"infinite," "eternal," "ecstasy," "transcen-dence" —doesn't mean that they don't refer to that something, nor is it a reason to abandon angels themselves to the saccharine and the mawkish. The poet and folk musician Leonard Cohen, a consummately nonmawkish and antisaccharine artist, a lover but not a sentimentalist, was asked in a 1984 interview by the journalist Robert Sward of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation about his affection for the word "angel." Detailing his attraction to the way the term was used by those great poets of beatitude Allen Gins-berg, Jack Kerouac, and Gregory Corso, Cohen admits that "I never knew what they meant, except that it was a designation for a human being and that it affirmed the light in an individual." This is a telling answer about the angelic, our attractions to them whether in Paradise Lost or It's a Wonderful Life, the manner in which such beings reflect the divinity in humanity and the humanity in divinity. They are otherworldly but near; alien but familiar; pure alterity and yet totally personal. Angels are the waystation between us and the unapproachable God. Cohen explains how the Beat poets were anything but maudlin in their attraction to the image of the angel; such a being to them wasn't evidence of cheap faith, but rather of the connections between the suffering soul and something in the great beyond, a light in the perennial darkness. "An angel is only a messenger, only a channel," Cohen says, and yet we're angels to each other, for the "fact that somebody can bring you the light, and you feel it, you feel healed or situated. And it's a migratory gift," suggesting that angels themselves are as much verb as noun. - ELYSIUM, a visual history of angelology, by Ed Simon, Introduction - page 8