Conductor Santtu-Matias Rouvali debuted with the Philadelphia Orchestra on 2.14.2026, alongside Hilary Hahn’s long-awaited comeback. Tchaikovsky’s Italian Capriccio was light and dreamy; Hahn’s Prokofiev Concerto showcased clarity and tone. Rouvali’s Shostakovich 6 felt raw yet rewarding. Thunderous applause closed the concert.

Read MoreEphemerality on Mahler 3rd Symphony

Budapest Festival Orchestra and conductor Iván Fischer performed Mahler's Symphony No. 3 at Carnegie Hall on 2.6.2026. Mahler's nature finds a voice, speaking profound secrets that man can only foresee in dreams. Running over 100 minutes, it depicts divine beauty and harshness, human sin and salvation.

A horn fanfare awakens Pan, god of the hall, on a January day at -15°C. Brass responds, joined by bass drum and solo trombone. The orchestra’s noble spirit reflects the earth’s breath, chaos, destruction, and creation. Double basses and percussion are placed around the hall, making Carnegie’s 2,800 seats breathe as one living creature. A march begins, life surging forth; Fischer draws crystal-clear sound, stirring the heart.

Read MoreBudapest Festival Orchestra Sings Nature at Carnegie Hall

At Carnegie Hall on 2.6.2026, the Budapest Festival Orchestra, led by Iván Fischer, opened with Pärt’s Summa, singing a Credo—“I believe.” Their voices, simple yet prism-like, created a wave of quiet light through the hall. In Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, Vengerov’s eloquent solo and the orchestra engaged in a lively dialogue. Brahms’ Symphony No. 2 revealed transparent interplay, with lines ascending and descending like light, while a Hungarian folk medley returned the music to its roots, inviting audience participation and joy.

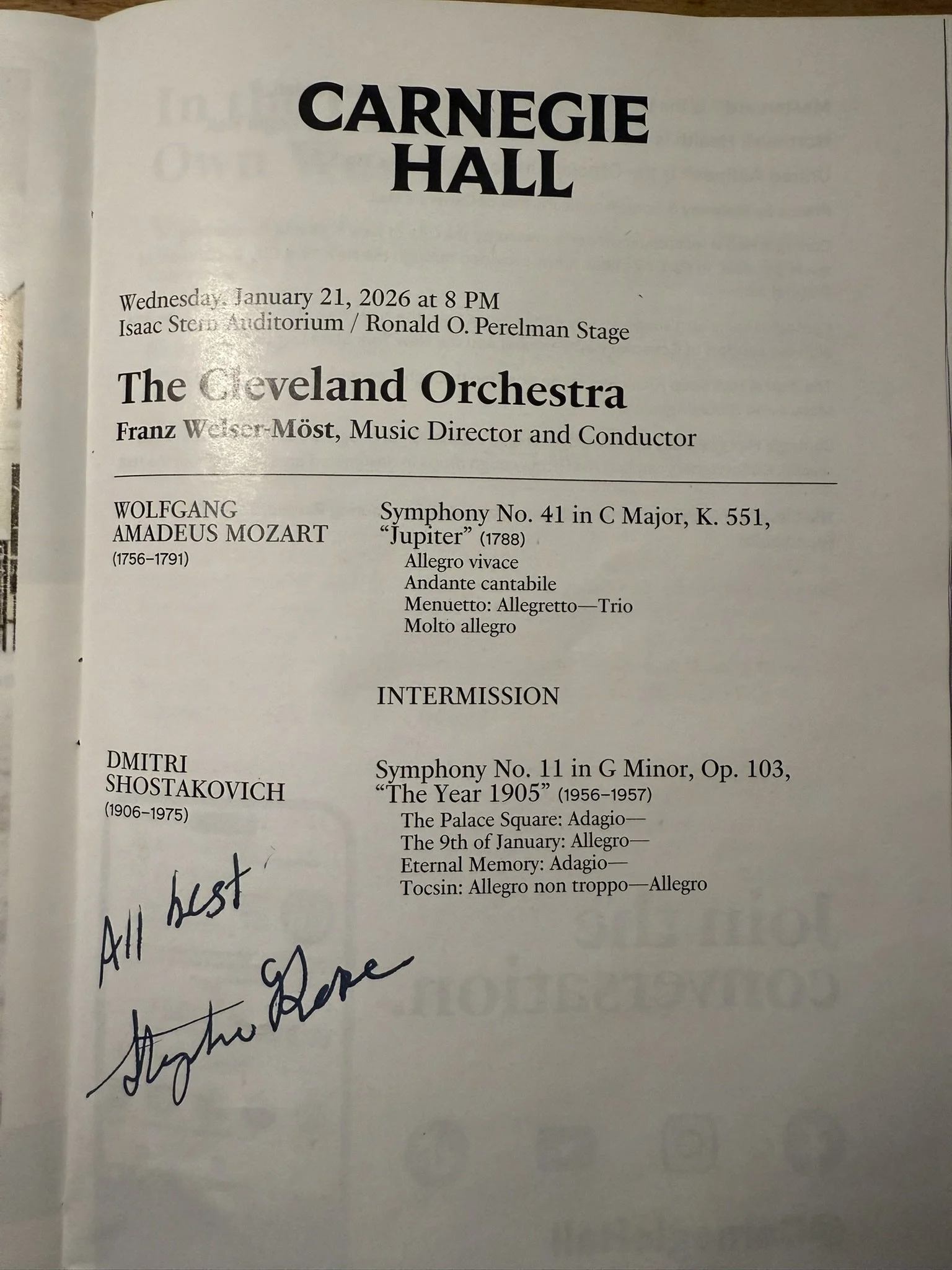

Read MoreCleveland Orchestra and Franz Welser-Möst at Carnegie Hall 2026

The Cleveland Orchestra performed Mozart’s Symphony No. 41 “Jupiter” and Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 11 at Carnegie Hall on January 21, 2026, under Franz Welser-Möst. In his program notes, Welser-Möst questioned what “authenticity” means, citing Mozart’s excitement over large forces and his belief that vibrato should arise naturally, like the human voice. Heard the day after Verdi’s Requiem, Jupiter sounded less light and transparent than physical and vocal, shaped by weight and breath. Shostakovich’s Eleventh, placed in the second half, avoided emotional excess; instead, Cleveland’s precise ensemble revealed cold repression through clarity and structure. As revolutionary fervor hardened into order and violence, the innocence and perfection of Mozart felt altered—almost like something already lost.

Read MoreCleveland Orchestra's Verdi Requiem at Carnegie Hall

Verdi’s Requiem resonated deeply. With the Cleveland Orchestra, Most, and the Cleveland Choir, the opening Requiem aeternam felt as if the sound arose from behind me. In Dies iræ, the intense orchestra conveyed the fear of sin, while the trumpet in Tuba mirum echoed through Carnegie Hall. In Recordare, the solo voice quietly pleaded for remembrance, and in Lacrimosa, the final Amen felt intimate and personal. In Offertorio and Sanctus, prayer and praise seemed to emerge from within; in Agnus Dei and Lux Æterna, voices and strings purified the heart. Finally, in Libera me, the fear of death and longing for salvation resonated powerfully through orchestra, choir, and solo singers—an unforgettable spiritual experience.

Read MoreDalia Stasevska's gravity in winter Philly

On Sunday afternoon, January 11th, at Annenberg Hall, Dalia Stasevska conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra. She shaped string phrasing into long, continuous lines, balanced textures so percussion and brass never obscured the sound, and moved effortlessly between contemporary and Romantic styles. With an orchestra as responsive and colorful as Philadelphia’s, her clarity of structure and spontaneous breathing brought the music vividly to life.

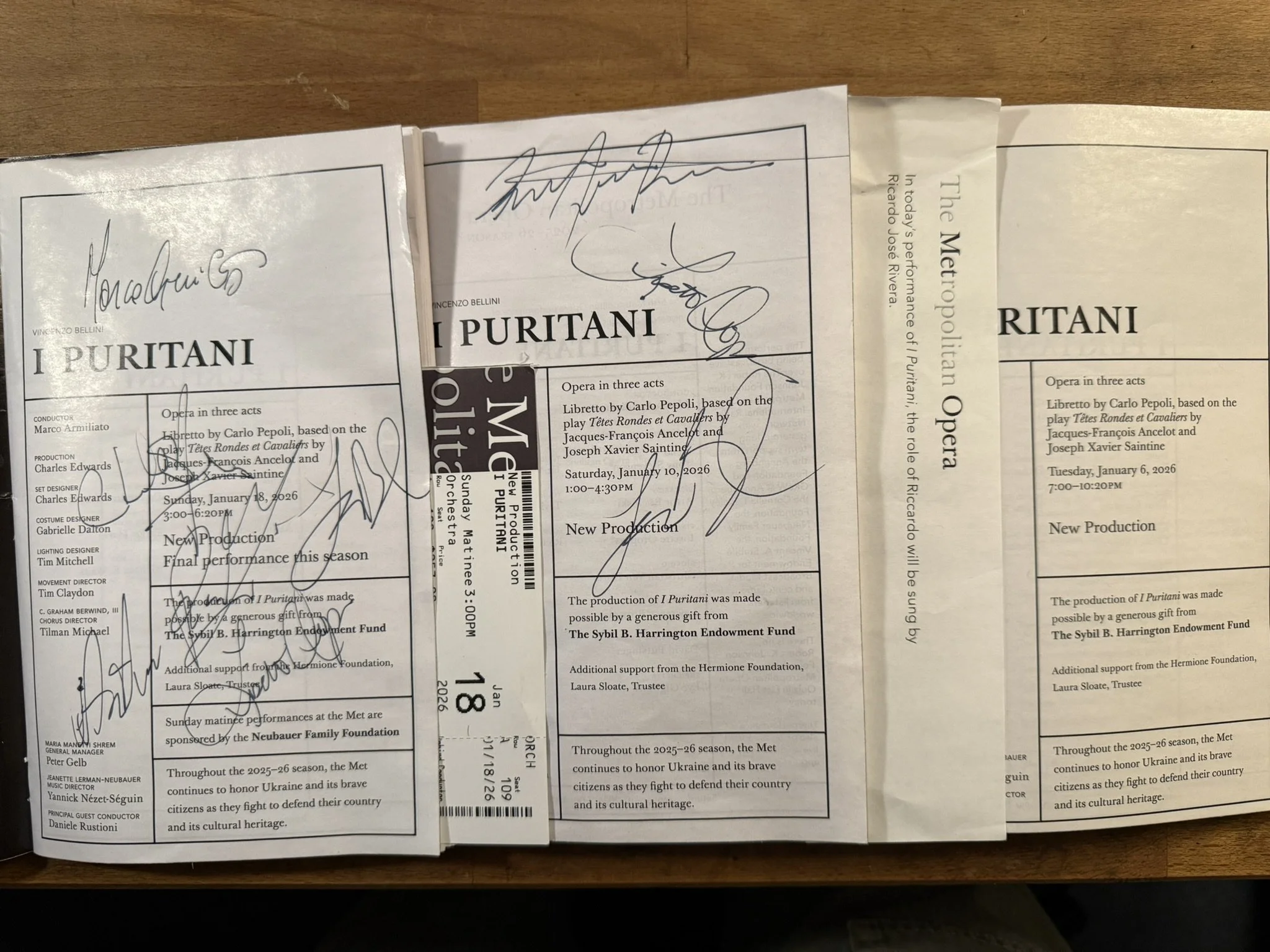

Read MoreI Puritani at Met Opera

Bellini’s I Puritani on January 6, 10, and 18 at the Metropolitan Opera. From the opening, the orchestra surged into the hunting-horn tutti, with strings, horns, bassoons, and timpani building intensity, while the Puritans’ triple-meter march intertwined with the chorus like a massive concerto. Lisette Oropesa’s Elvira floated above the violas’ weight, her delicate voice revealing the trembling of her heart. Artur Ruciński’s Riccardo sang unbroken lines that seemed to stretch time, while the orchestra responded with harmony and articulation, creating a vivid dialogue between voice and ensemble.

I Puritani combines simple marches into a complex, kaleidoscopic structure, revealing both the purity of the human heart and the expressive freedom of bel canto.

Read MoreBlanc Canon

Preface

Sound, rising from silence,

Fingertips find the edge of the chair.

Breaths overlap.

Time slips away.

沈黙から生まれた響きは

指先で椅子の縁に触れ

呼吸が重なり時間を忘れる

Presence / Duo Seraphim

The spatiality of sound is invisible, yet felt like sculpture. In Monteverdi’s Duo seraphim, two voices become three, then merge into one; syllables stretch, words do not end, and time itself sways. In Jacobs’ performance, the melisma aligns with breath, and sound approaches silence. Without explaining doctrine or narrative, Monteverdi lets listeners experience the Trinity through sound alone. One simply senses presence, and the music becomes the very air of the space.

Read MoreMahler in Philly on January

The concert opens with John Adams’s kinetic Short Ride in a Fast Machine, followed by Samuel Barber’s lyrical Violin Concerto with Augustin Hadelich. It concludes with Mahler’s transparent and ironic Symphony No. 4, featuring soprano Joélle Harvey, under Dalia Stasevska.

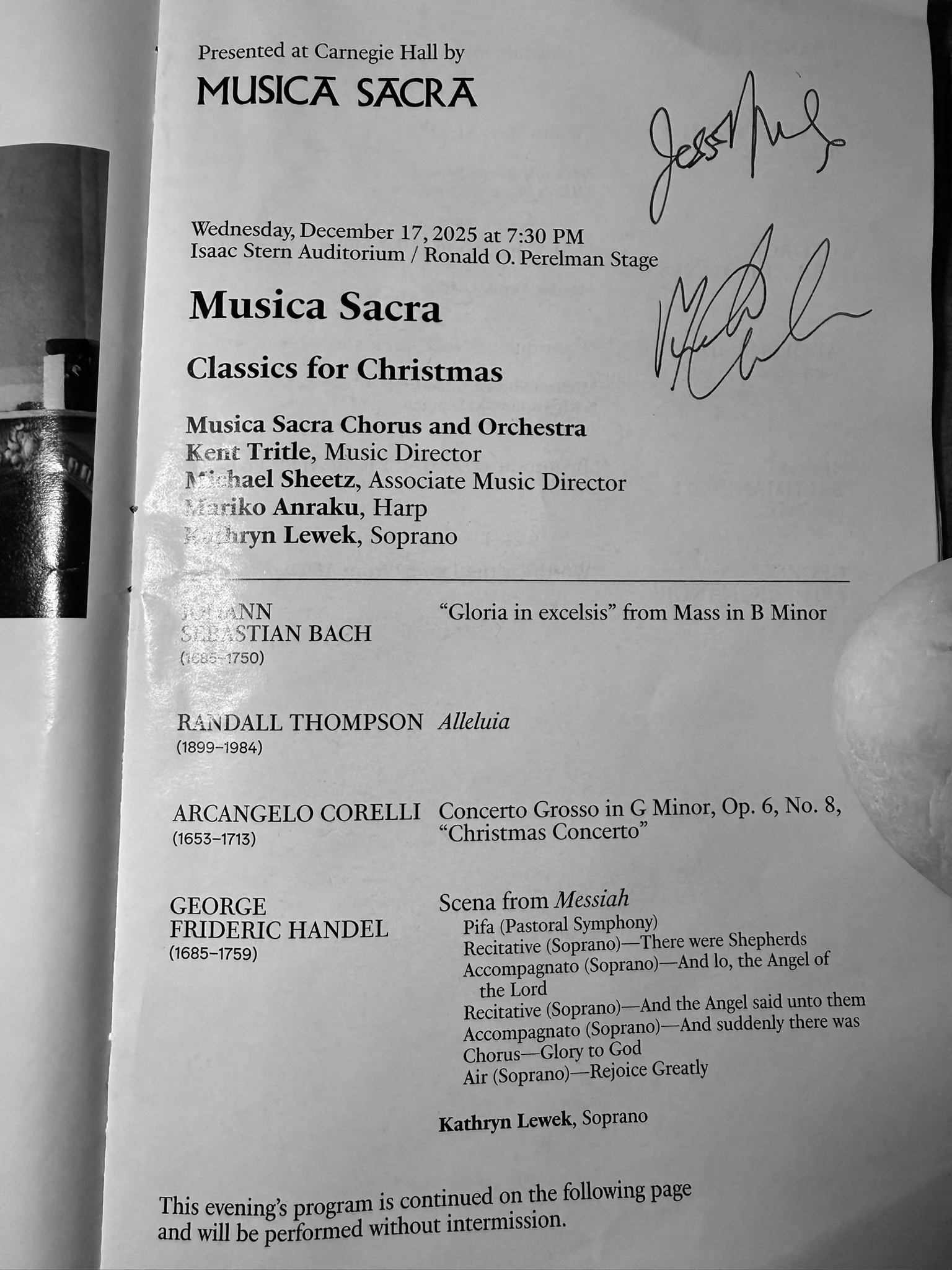

Read MoreMusica Sacra's Classics for Christmas at Carnegie Hall

New York’s choral and orchestral ensemble Musica Sacra performed “Classics for Christmas” at Carnegie Hall on December 17, 2025. The program featured Christmas-related works by Bach, Thompson, Corelli, and Handel, with soprano Kathryn Lewek and harpist Mariko Anraku as soloists. Highlights included Bach’s Gloria in excelsis Deo, excerpts from Handel’s Messiah, and Rachmaninoff’s Bogoroditse Devo, creating a rich, festive, and deeply moving concert. The performance was led by conductor Kent Tritle.

Read MoreDaniil Trifonov at Carnegie 2025

Trifonov’s program traced Russian modernism and Romantic expression, opening with Taneyev’s Prelude and Fugue, where he highlighted clarity, restrained lyricism, and transparent counterpoint. Prokofiev’s Visions fugitives revealed fleeting humor and delicacy, while Myaskovsky’s single-movement Sonata conveyed shadow, tension, and virtuosity with precise control. In Schumann’s Sonata, he contrasted Florestan and Eusebius through agile scherzos, lyrical arias, and a spirited finale, uniting improvisatory freedom with poetic depth. Across the program, Trifonov balanced technical mastery, expressive nuance, and psychological insight, illuminating the music’s inner voice and emotional breadth.

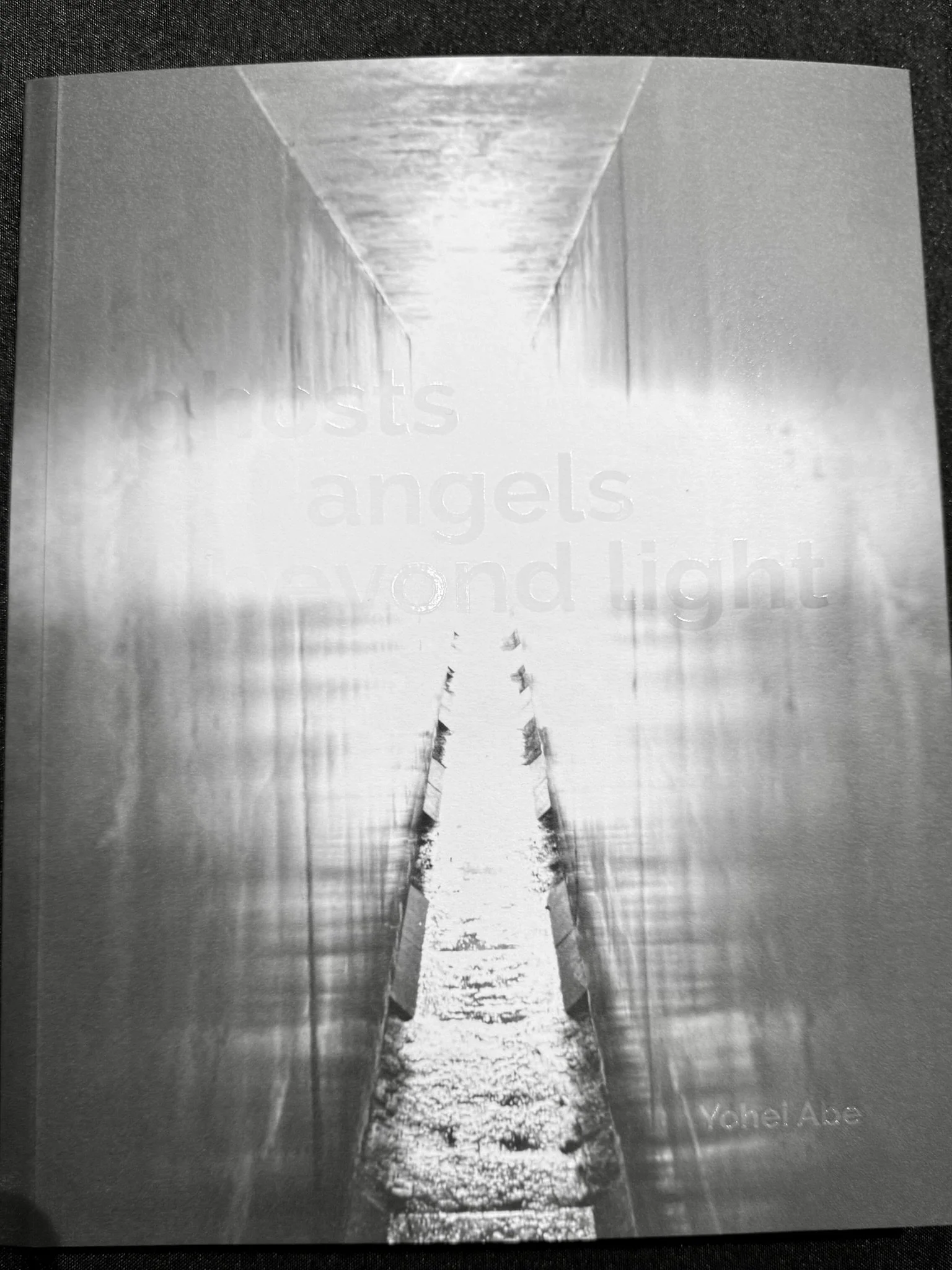

Read MoreYohei Abe, the photo book released in SF

Yohei Abe, a long-time friend of classicasobi and my host at Balse, has released the photobook Ghosts, Angels, Beyond Light. Four years ago, a personal event led him to decide to create this photo book. He had been taking photos all along, but with the decision to publish a photo book, he planned it, and the launch event was held at the Leica Gallery in San Francisco on 12.11.2025, called "Vision to Volume" by Leica.

Read MoreThe way of seeing-After Ruth Asawa at MOMA

The way one sees others determines one’s actions, and repeated actions determine one’s way of being.

This forms a chain of perception → action → existence. How one interprets the world and other people shapes choices and behavior. The same event can provoke completely different responses depending on whether it is perceived as something to trust or something to fear. Through repeated actions, a person’s posture, character, and ultimately “what kind of person they are” take shape. Intentions and ideals matter less than what is actually done; existence is defined by action. One’s way of being is not a matter of personality, but the accumulation of thought and behavior.

Read MoreFrei aber froh! The Chamber Orchestra of Europe and Yannick Nézet-Séguin in Philly.

Compared with the Stern Auditorium at Carnegie, Anderson Hall has a longer reverberation. Even 1st row, the sound arrives with delay and swells as it reaches the listener. Because the resonance feels prolonged, the musical shapes can sound somewhat blurred. Some people describe this as a “rich acoustic,” but true sound richness originates from the artists. Acoustics may support that richness, yet this hall demands a different kind of shaping from the musicians. Still, they skillfully adjusted the relationship between their positions on stage and the sounds they produced, and once again unfolded a richly satisfying Brahms.

Read MoreTragedies, solve by individualities/Chamber Orchestra of Europe and Yannick Nézet-Séguin at Carnegie Hall

Chamber Orchestra of Europe and Yannick Nézet-Séguin's All Brahms at Carnegie Hall on December 9, 2025.

Chamber Orchestra of Europe

Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Conductor

Veronika Eberle, Violin

Jean-Guihen Queyras, Cello

Program

ALL-BRAHMS PROGRAM

Tragic Overture

Double Concerto

Symphony No. 1

Read MoreLatvians: A Tribute to Arvo Pärt

Three Latvian musicians, Gidon Kremer, Giedrė Dirvanauskaitė, and Georgijs Osokins, had a trio recital at Zankel on 12.4.2025

Read MoreBrilliant Cello, Elena Ariza with Juilliard Orchestra

When solo cellist Elena Ariza came to the stage, the orchestra and audience erupted in excitement. After a six-minute introduction, her solo begins, in variations four and five, where she mistakes a kidnapped lady and charges forward, slamming, and then the bass continues. Elena then immerses herself in her thoughts of an imaginary lover. Strauss was singing. It sounded like Waldner's singing in Arabella. She was completely Don Quixote, her bow strokes flawless, her lyrical and passionate singing conveyed directly.

Read MoreCaroline Bembia Harp Recital

Caroline Bembia, harp in a small church, 11.22.2025 —it was my first time attending a harp recital. Unlike the sharp attack of a piano or the vibration of percussion, her sound simply emerged and spread through the space. Unlike Lincoln Center’s cold precision or the Met’s rich resonance, the natural reverberation of the church walls let me fully appreciate the harp’s unique tone and dynamic range.

Read MoreThe Marlboro Soloists at Weill Recital Hall

11.21.2025 Musicians From Marlboro at Weill Recital Hall. A chamber music group made up of young musicians associated with the Marlboro Music Festival in the United States. The festival, established in 1951, is known as a place where young and experienced musicians come together to study and perform chamber music. Selected members of the group give concerts both in the U.S. and abroad.

Read More