Conversations with Cezanne

Here is the way Cézanne's palette was prepared when I met him in Aix:

Yellows

Brilliant yellow

Viridian (Veronese green)

Naples yellow

Greens

Emerald green

Yellows

Chrome yellow

Green earth

Yellow ochre

Raw sienna

Vermillion

Blues

Indian red (red earth)

Cobalt blue

Ultramarine blue

Prussian blue

Peach black

Burnt sienna

Reds

Madder lake

Carmine lake

Burnt crimson lake

EMILE BERNARD

page 72 -

Documents of Twentieth-Century Art

Conversations with Cézanne

Michael Scott Doran, Julie Lawrence Cochran (Translator), Richard Shiff (Introduction)

Conversations with Cezanne

He claims that this method of working, which is his alone, is the only correct one, the only one leading to a serious result. He mercilessly condemns all preference for simplification which does not pass through submission to nature by means of a meditative and progressive analysis. If a painter is easily satisfied, it is because, according to Paul Cézanne, his vision is mediocre, his temperament practically worthless.

Leonardo da Vinci put forth a similar idea in his treatise on painting when he said, "The painter who has no doubts will profit little from his studies. When a work of art surpasses the judgment of the creator, he who works advances little; but when his judgment rules his works, those works become more and more perfect if inconsistency does not interfere." The artist will arrive at self-knowledge and the perfection of his art not through patience, therefore, but through love that gives insight and the desire to analyze in greater depth and to improve. He must extract from Nature an image which will be, properly speaking, his own; and only through analysis, if he has the strength to press it to the end, will he make himself known ultimately, unambiguously, abstractly.

page 37 -

Documents of Twentieth-Century Art

Conversations with Cézanne

Michael Scott Doran, Julie Lawrence Cochran (Translator), Richard Shiff (Introduction)

Conversations with Cezanne

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Denis (like many others) observed that artists of his own age were being dehumanized by the leveling effects of modern urban life mechanization, commodification, standardization, social regulation-all leading to impoverishment of both intellectual and spiritual experience. He argued that the remedy could be found in an "abstract ideal, the expression of inner [mental] life or a simple decoration for the pleasure of the eyes." Under the circumstances, the representational arts would strive to mask out dull environmental realities, "evolving toward abstraction." However much this kind of "abstraction" might appeal to the intellect and imagination (subjective "inner life"), it would retain a distinct material component, located in a purified form and a straightforward procedure (the objective "beauty" of "a simple decoration"). Cézanne was exemplary because his marks appeared independent of any strict mimetic function and were also very physical, therefore representing a material (not conceptual) abstraction of the painting process. This was an aestheticized, humanized materialism, intense in both sensation and spirit; it seemed fit to counter the anesthetizing materialism of modern bourgeois existence.

page 31 -

Documents of Twentieth-Century Art

Conversations with Cézanne

Michael Scott Doran, Julie Lawrence Cochran (Translator), Richard Shiff (Introduction)

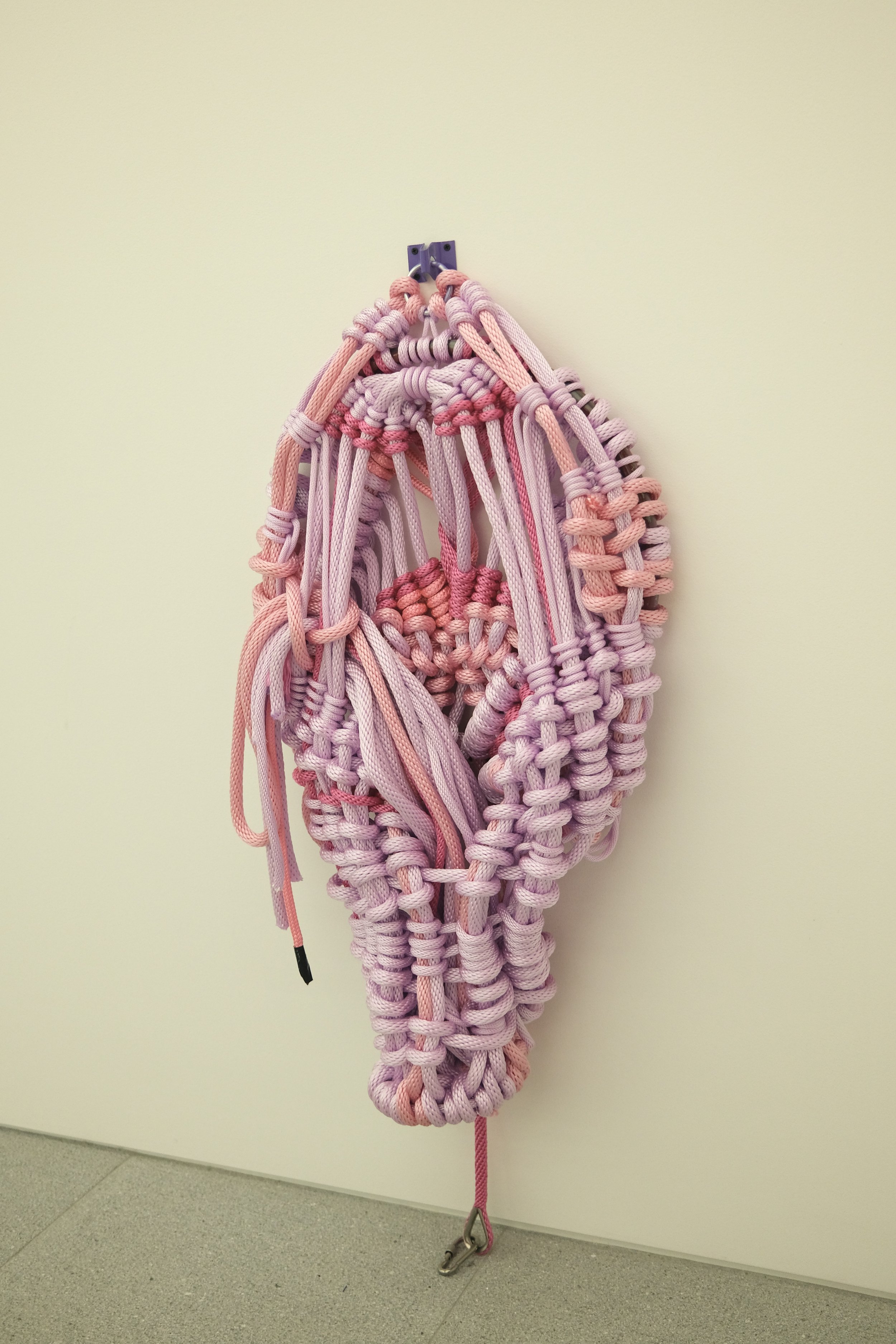

Simone Leigh

May 26, 2024–Jan 20, 2025

LACMA, Los Angeles

Daniel Pešta - Venezia 2024

Venezia Biennale Arte - Trevor Yeung, Hong Kong

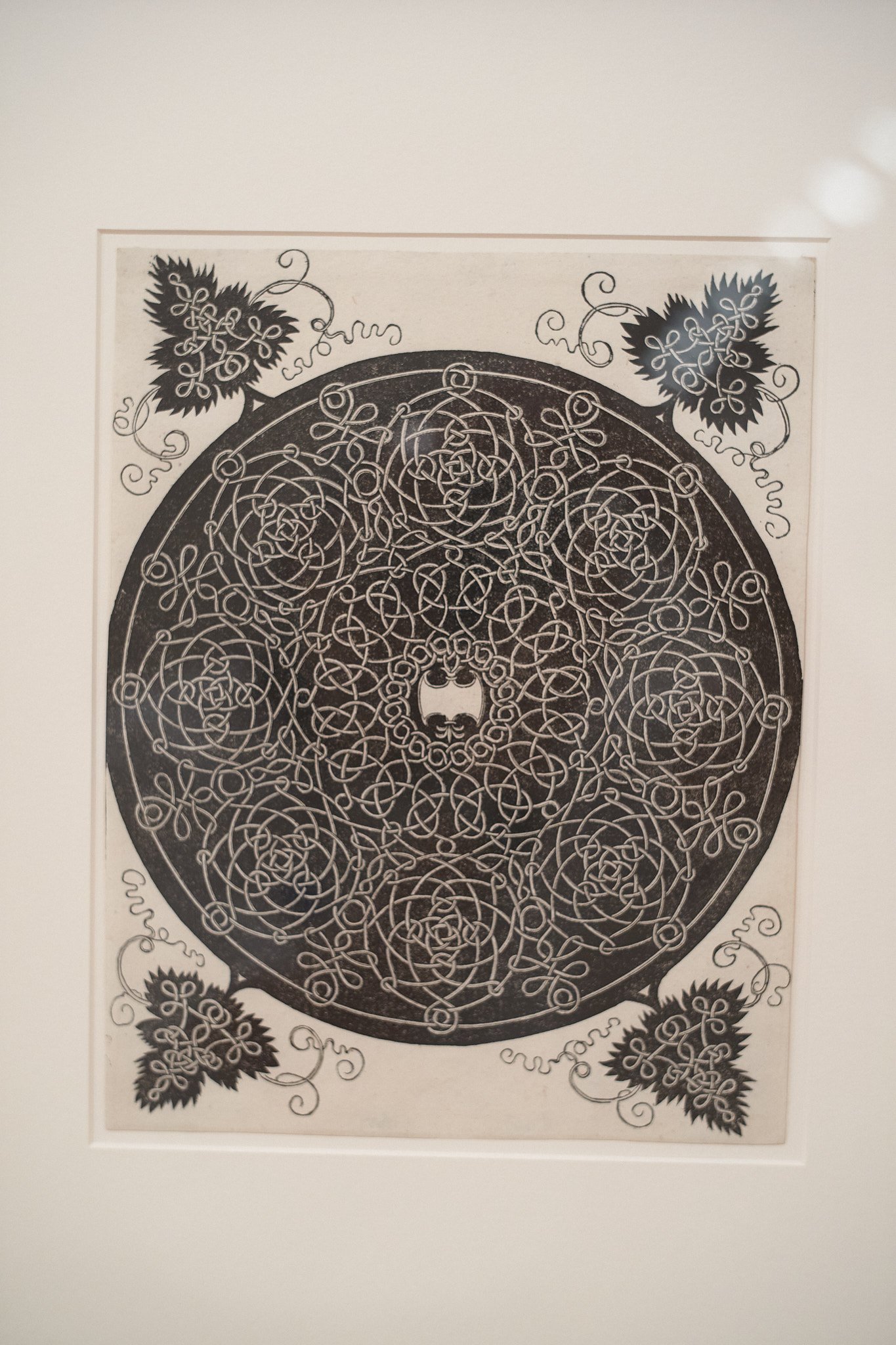

Sum of the Parts: Serial Imagery in Printmaking, 1500 to Now

Esthella Provas

Jacqueline Surdell

Conversations with Cezanne

When Lecomte evaluated Cézanne so intelligently in 1899, "abstraction" had not yet settled into its twentieth-century, formalist definition. Nor had images called "abstract" abandoned representational reference, as they would begin to do not long after Cézanne's passing. The meaning of

"abstraction," circa 1900, was fluid and confused, an amalgam of contested notions. Regardless of anything Cézanne said, it was his technique that caused many of his witnesses to link the autonomy of his form and the purity of its beauty to a process of abstraction. This turn in interpretation entailed a certain irony: "form" and "beauty" were conceptual entities suited to endless verbal philosophizing, precisely what Cézanne disliked in Bernard among others. To reconcile abstraction, itself an "abstract" notion with the very physical nature of Cézanne's painting, most of those familiar with him claimed that his abstraction developed from the senses, not the intellect—more intuitive harmony than science of color, more spontaneous rhythm than planned geometry. This variant of "abstraction" broke from the term's nineteenth-century connotation of intellectual excess (we still say that certain arguments are "too abstract," or that a mentally distracted person has an "abstract" look). Lecomte's perception that Cézanne's style satisfied antithetical demands coming from impressionist naturalism and symbolist idealism was ingenious and should have been adequate to the situation; but other commentators began to acknowledge somewhat different alignments, cognizant of competing notions of "abstraction." For Denis, the conflict between Monet's impressionism and Gauguin's symbolism amounted to a dispute between sensualist lovers of nature and rationalist devotees of abstract form. Reacting to attitudes that troubled him in others, Denis complicated matters by switching sides in the ongoing debate. First he praised, then he denigrated abstraction, lamenting Cézanne's inadvertent role in furthering it.

Why all this happened is crucial to the historical fortune of Cézanne's art. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Denis (like many others) observed that artists of his own age were being dehumanized by the leveling effects of modern urban life-mechanization, commodification, standardization, social regulation—all leading to impoverishment of both intellectual and spiritual experience. He argued that the remedy could be found in an "abstract ideal, the expression of inner [mental] life or a simple decoration for the pleasure of the eyes.", Under the circumstances, the representational arts would strive to mask out dull environmental realities, "evolving toward abstraction." However much this kind of "abstraction" might appeal to the intellect and imagination (subjective "inner life"), it would retain a distinct material component, located in a purified form and a straightforward procedure (the objective "beauty" of "a simple decoration"). Cézanne was exemplary because his marks appeared independent of any strict mimetic function and were also very physical, therefore representing a material (not conceptual) abstraction of the painting process. This was an aestheticized, humanized materialism, intense in both sensation and spirit; it seemed fit to counter the anesthetizing materialism of modern bourgeois existence.

page 30 -

Documents of Twentieth-Century Art

Conversations with Cézanne

Michael Scott Doran, Julie Lawrence Cochran (Translator), Richard Shiff (Introduction)

Elysium: A Visual History of Angelology

Krishnamurti's major theological contention could be summarized by his statement "Truth is a pathless land," the belief that the angelic, or the divine, or the transcendent, or the absolute must forever be inaccessible to logical language, that no route can bring the initiate to that kingdom, and so the only means of approaching it is poetic rather than rational. At a 1929 address in the Netherlands, Krishnamurti proclaimed, "Truth, being limitless, unconditioned, unapproachable by any path whatsoever, cannot be organized ... A belief is purely an individual matter, and you cannot and must not organize it. If you do, it becomes dead, crystallized; it becomes a creed, a sect to be imposed on others... Truth cannot be brought down, rather the individual must make the effort to ascend to it." Just as quantum mechanics posits that all sorts of truths about the universe —say, the exact location or velocity of an individual particle —must remain ambiguous and are only decided upon by the arbitrary intercession of the observer, Krishnamurti describes something similar about the divine. Despite his training in Theosophy, such beliefs are perfectly consistent with many interpretations of Eastern religions, but they're also congruent with the idealist mystical belief that the universe only exists if it's being observed, and that God and his retinue are always doing the observing. Both Krishnamurti and Bohm were radical monists, believing in one substance, but rather than matter that substance was mind. The conclusions of quantum mechanics-demonstrated by mathematics and proven by experimentation-were disturbing to physicists who had been trained in the static model of Newtonian science; that some results seem to require consciousness appeared anathema to them. Yet the numbers were what the numbers were, the observations and experiments revealed what they had. On some level, there was a wisdom to assuming that the counterintuitive logic of quantum theory implied that consciousness permeated existence, as that would be the only way to make any sense of such strange results. As Bohm would audaciously declare in an essay published in 1987 in the collection Quantum Implications: Essays in Honor of David Bohm, "Even the electron is informed with a certain level of mind."

Elysium: A Visual History of Angelology

Page 340

Elysium: A Visual History of Angelology

Cornelius Agrippa in The Occult Philosophy, one of the most influential theurgic texts of the Renaissance, states the Neoplatonist ethos succinctly when he writes that the "world is an elemental, celestial and intellectual triad where every lower thing is ruled by something higher and receives that mighty influence whereby-through angels, heavens, stars, elements. animals, plants, metals and stones —the archetypal and supreme Craftsman transfers his omnipotent powers into us, having made and created all of them to serve us."

Elysium: A Visual History of Angelology

Ed Simon - pg 118

Keiichi Tanaami: Adventures in Memory

Christiane Pooley " Geographies of Love "

Yukie Ishikawa, Akane Saijo

Sum of the Parts: Serial Imagery in Printmaking, 1500 to Now

and some Gustave Moreau, Salomé Dancing before Herod, 1876 from their permanent collection

The Miraculous Arms Curated by Martha Kirszenbaum

Barbati, Venezia an arena, a group exhibition presented in collaboration with Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

Elysium: A Visual History of Angelology

Helpful to remember, lest one confuse contextual representation with reality when parsing the intricacies of the incorporeal and ineffable. Angels don't have blond hair because angels don't have hair; angels don't have blue eyes because they don't have eyes (or they have dozens of them). There is nothing wrong, of course, with imagining angels in the form of humans, only with mistaking a small segment of examples for the universal standard. Which is what's so fascinating about the earliest representations of such beings, which flout the conventions of the angelic as they've been transmitted in Western culture, or for that matter the response from those who suffered under colonialism and imagined angels as appearing like themselves. In the contact zones of early modern colonialism, beginning in the sixteenth century and continuing until the modern era, and with a particular zenith during the so-called Age of Reason, people developed syncretic religious traditions between Christianity and their own indigenous faiths, in which divine intermediaries often played an integral role. From Africa to Latin America, India to North America, artists often depicted angels in the visual idiom of their own cultures.