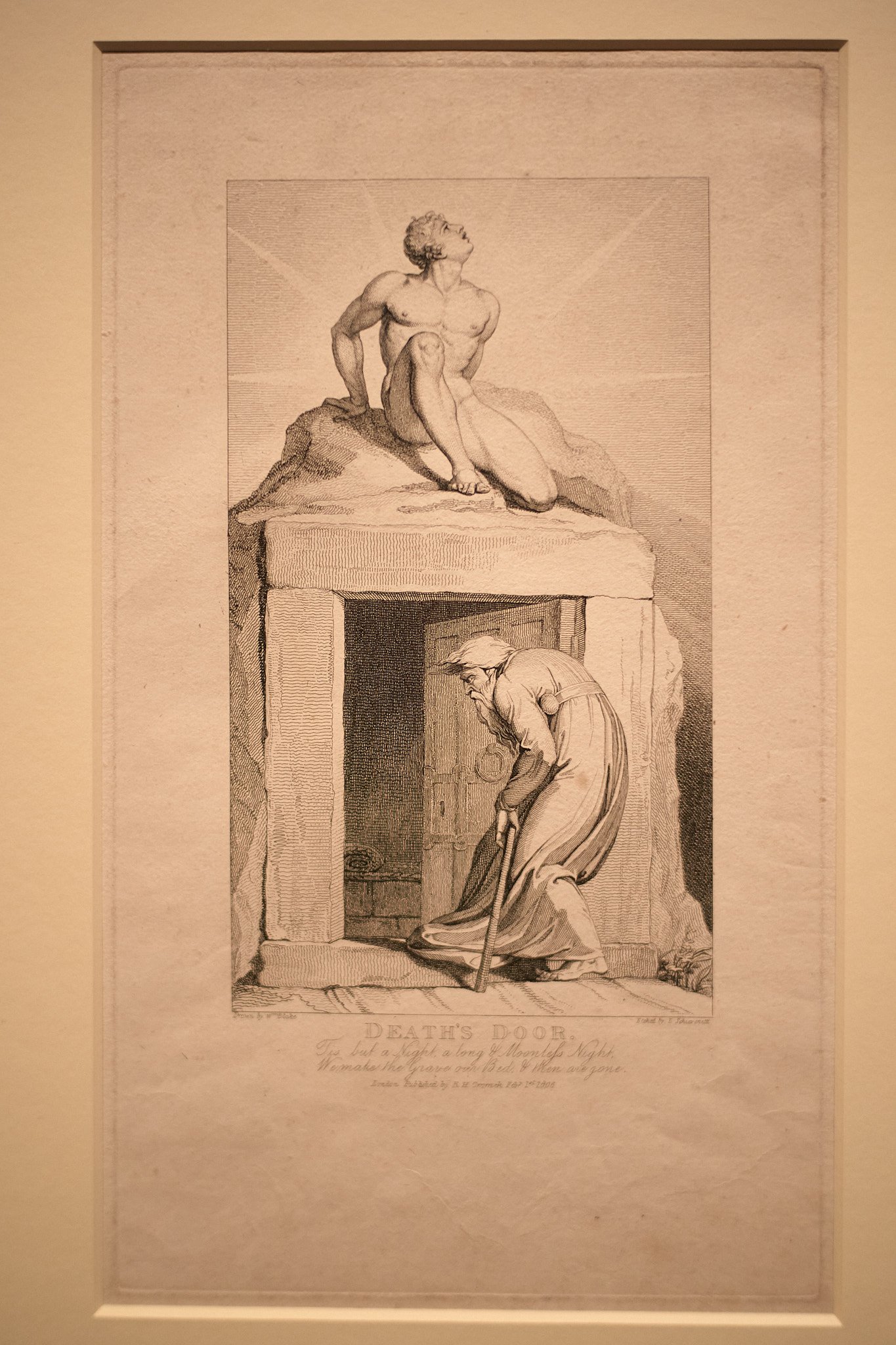

William Blake, Getty Center

From Academic Emulation toward Romantic Originality

History of Modern Art, seventh edition, H.H. Arnason Elizabeth C. Mansfield, Chapter 1, page 4

The emphasis on emulation as opposed to novelty begun to lose ground toward the end of the eighteenth century when a new weight was given to artistic invention. Increasingly, invention was linked with imagination, that is to say, with the artist’s unique vision, a vision unconstrained by academic practice and freed from the pictorial conventions that had been obeyed since the Renaissance. This new attitude underlies the aesthetic interests of Romanticism. Arising in the last years of the eighteenth century and exerting its influence well into the nineteenth, Romanticism exalted humanity's capacity for emotion. In music, literature, and the visual arts, Romanticism is typified by an insistence on subjectivity and novelty. Today, few would argue that art is the simply the consequence of creative genius. Romantic artists and theorists, however, understood art to be the expression of and individual’s will to create rather than a product of particular cultural as well as personal values. Genius, for the Romantics, was something possessed innately by the artist: It could not be learned or acquired. To express genius, then, the Romantic artist had to resist academic emulation and instead turn inward, toward making pure imagination visible. The British painter and printmaker William Blake (1757-1827) typifies this approach to creativity.