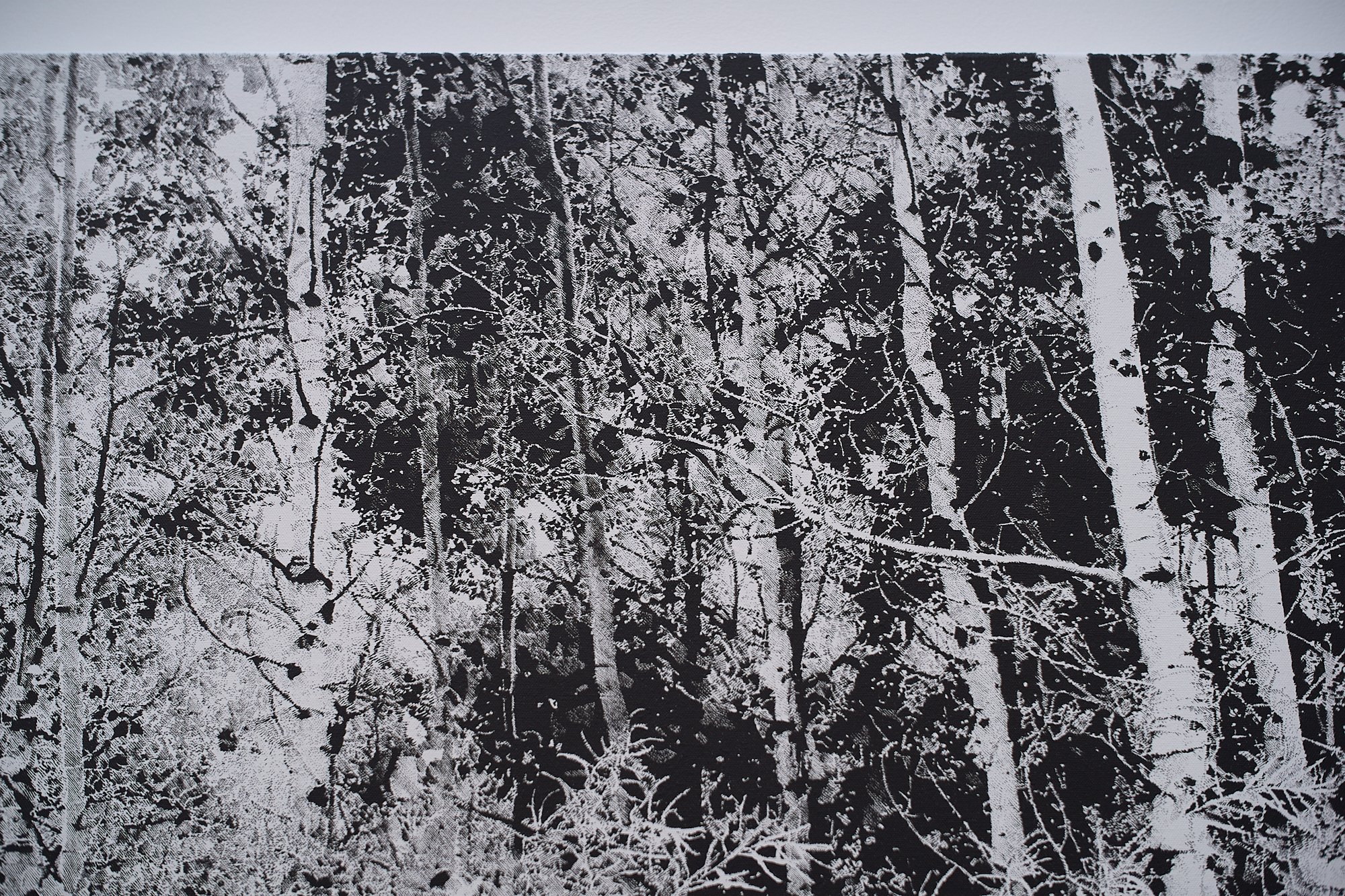

if we want to understand the way in which northern art developed, we must appreciate this infinite care and patience of Jan van Eyck. The southern artists of his generation; the Florentine masters of Brunelleschi’s circle, had developed a method by which, nature could be represented in a picture with almost scientific accuracy. They began with the framework of perspective lines, and they built up the human body through their knowledge of anatomy and of the laws of foreshortenning. Van Eyck took the opposite way. He achieved the illusion of nature by patiently adding detail till his whole picture became like a mirror of the visible world. The difference between northern and Italian art remained important for many years. It is a fair guess to say that any work which excels in the representation of the beautiful surface of things, of flowers, jewels or fabric, will be by a northern artist, most probably by an artist from the Netherlands; while a painting with bold outlines, clear perspective and a sure mastery of the beautiful human body, will be Italian. - The Story of Art, E.H. Gombrich pg 239

words of Annie Leibovitz from Master Class

I was in Monument Valley for a few days and went all over it. I rented a helicopter, I made several side swipes by the fingers and took pictures. And of course it couldn’t help but be somewhat blurred. It’s bigger than just being out of focus. It was really emotional landscape.

Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

The future is fixed, but we move around in infinite space -

The Story of Art, E.H. Gombrich pg 229

Brunelleschi was not only the initiator of Renaissance architecture. To him, it seems, is due another momentous discovery in the field of art, which also dominated the art of subsequent centuries - that of perspective. We have seen that even the Greeks, who understood foreshadowing, and the Hellenistic painters, who were skilled in creating the illusion of depth, did not know the mathematical laws by which objects appear to diminish in size as they recede from us. We remember that no artist could have drawn the famous avenue of trees leading back into the picture until it vanishes into the horizon. It was Brunelleschi who gave artists mathematical means of solving this problem; and the excitement which this caused among his painter-friends must have been immense. -

How to Take Smart Notes, Sonke Ahrens page 128

Thinking and creativity can flourish under restricted conditions and there are plenty of studies to back that claim (cf. stokes 2021; Rheinberger 1997). The scientific revolution started with the standardization and controlling of experiments which made them comparable and repeatable. Or think of poetry: It imposes restrictions in terms of rhythm, syllables or rhymes. Haikus give the poet very little room for formal variations but that doesn’t mean they are equally limited in term of poetic expressiveness. On the contrary: It is the strict formalism that allows them to transcend time and culture. -

Mastery, Robert Greene, page 84

Let us state it in the following way: At your birth a seed is planted. That seed is your uniqueness. It wants to grow, transform itself, and flower to its full potential. It has a natural assertive energy to it. Your life’s task is to have a destiny to fulfill. The stronger you feel and maintain it - as a force , a voice, or in whatever form - the greater your chance for fulfilling this Life’s Task and achieving mastery.

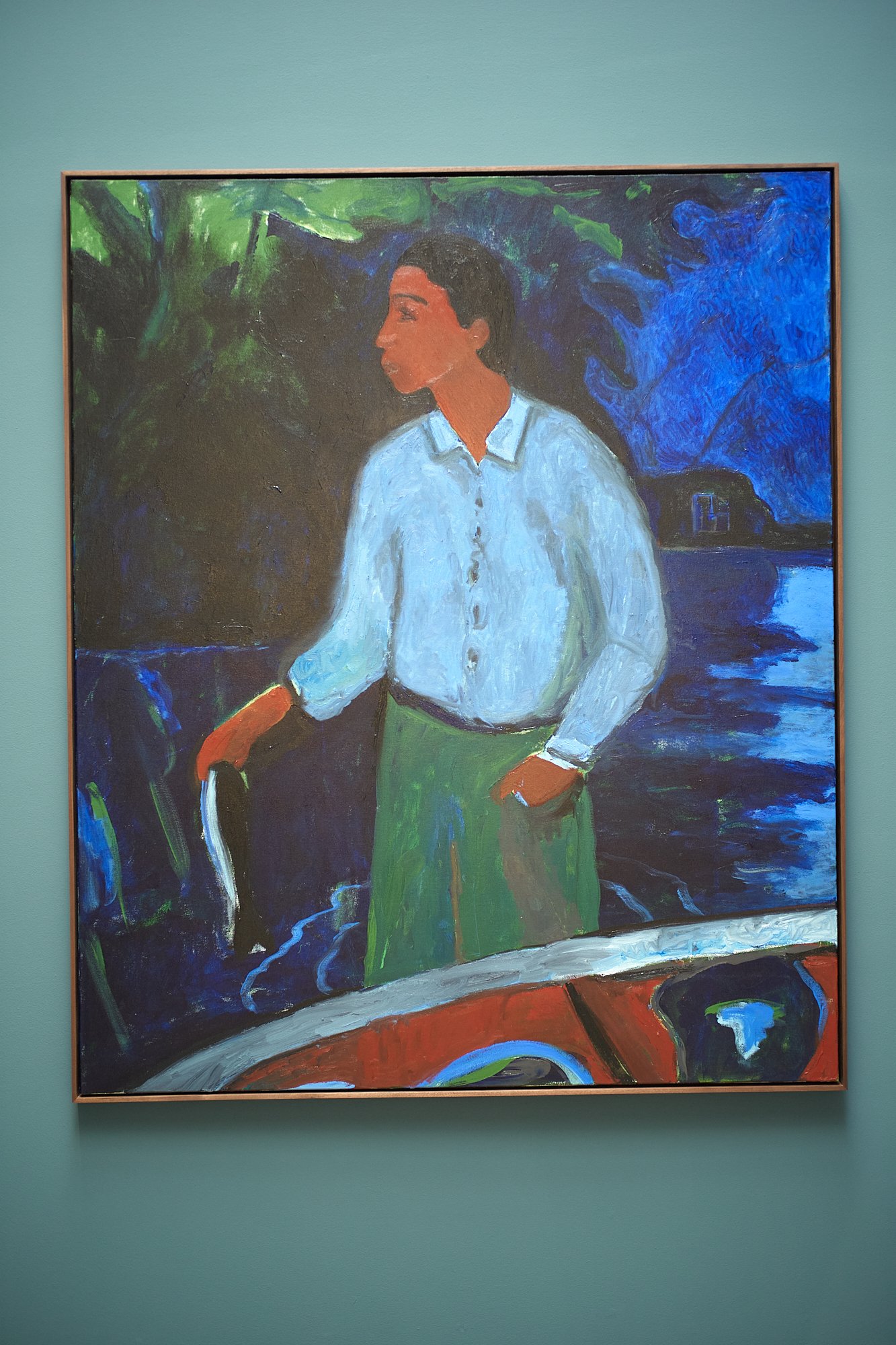

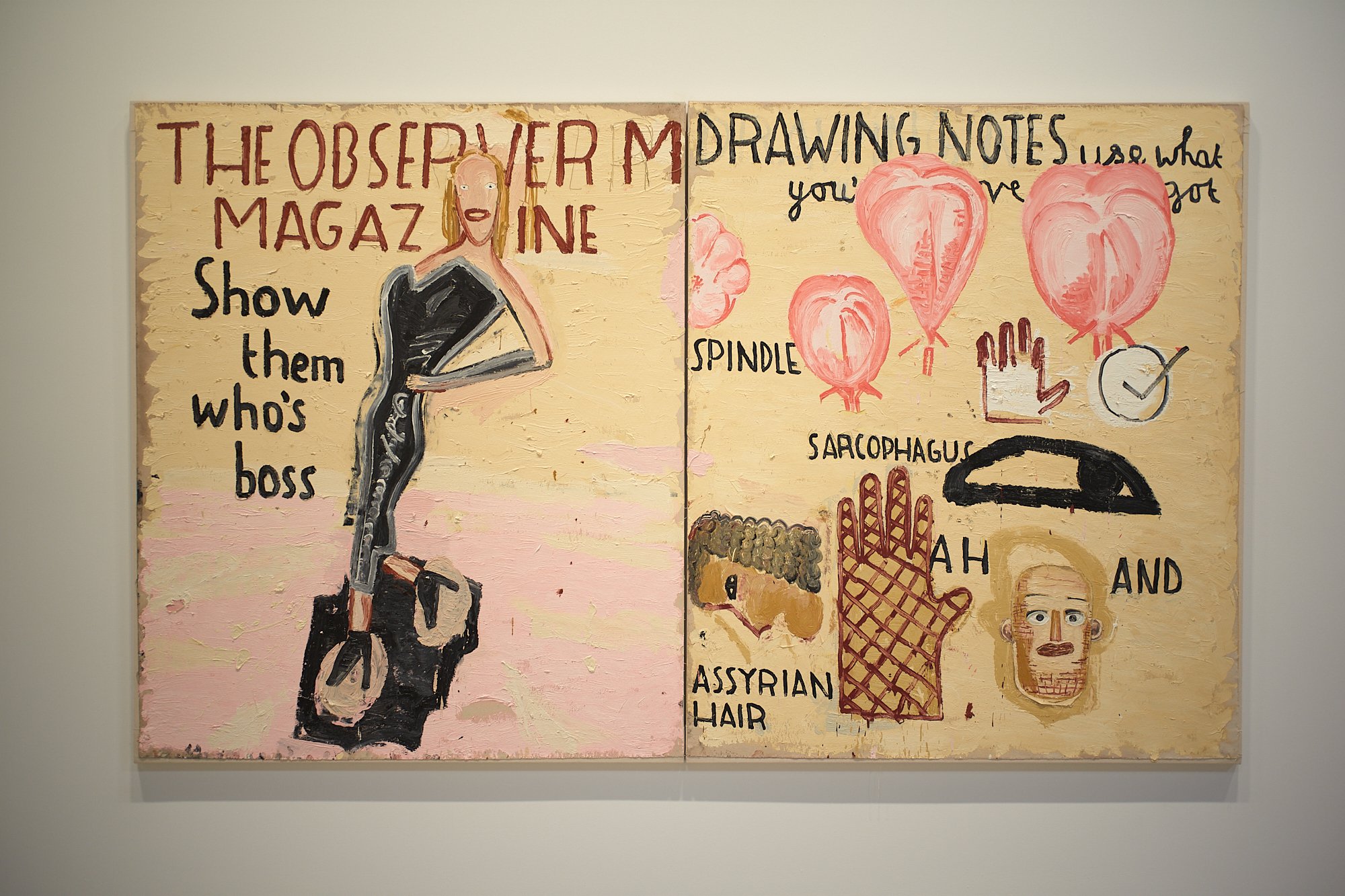

"Pictures Girls Make": Portraitures Curated by Alison M. Gingeras

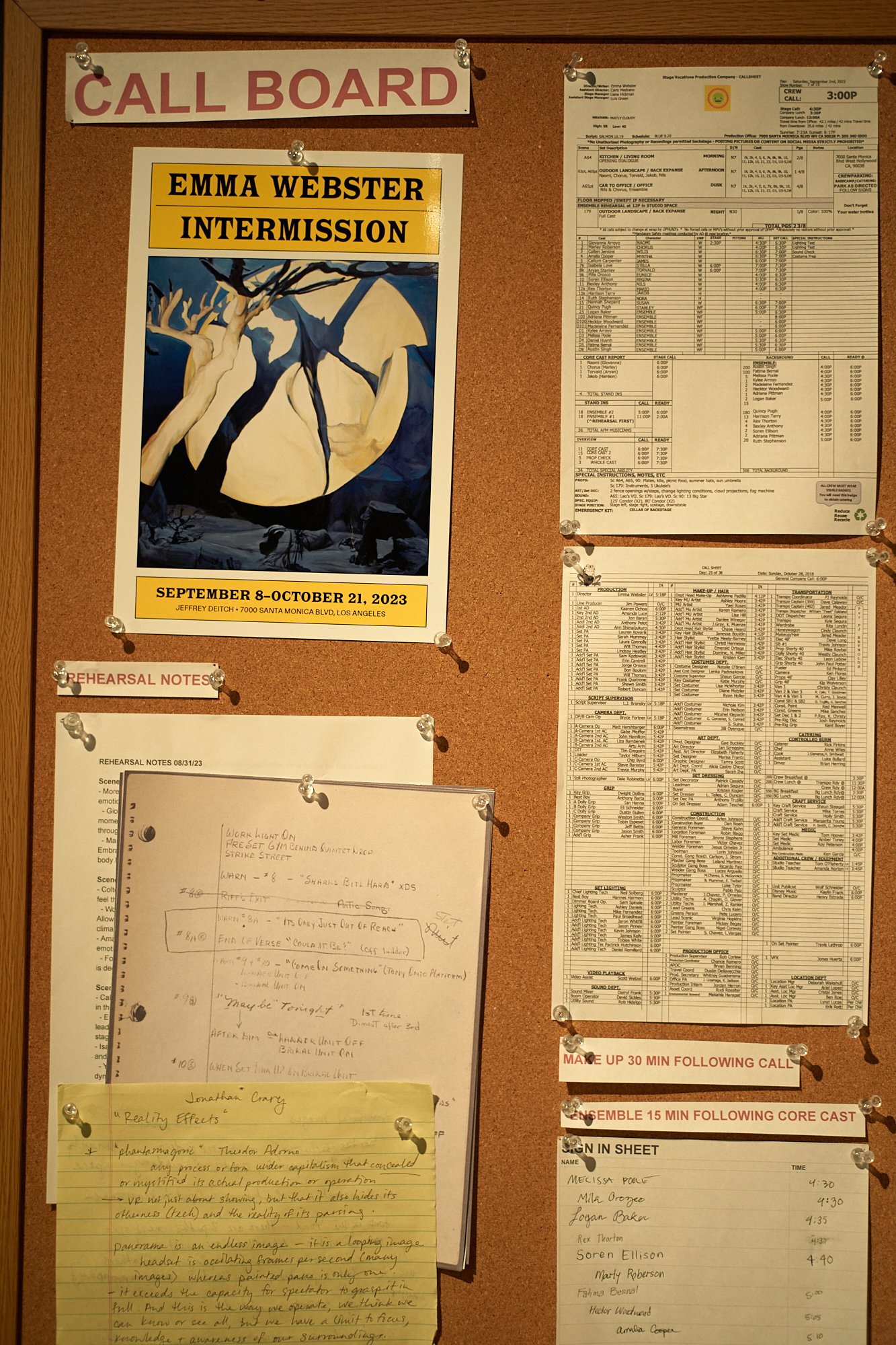

Emma Webster: Intermission

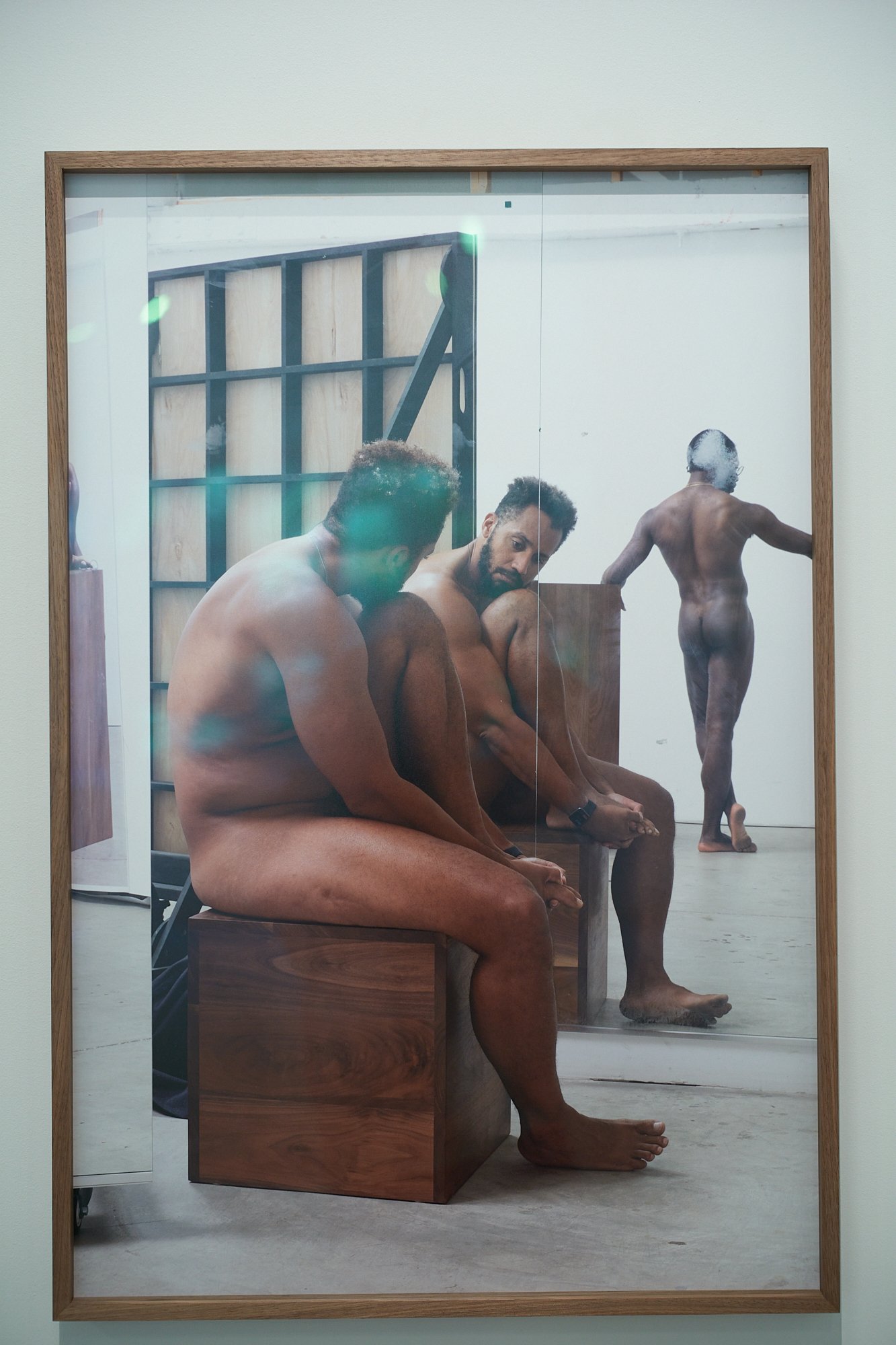

Vanessa Beecroft: Rules of Non-Engagement

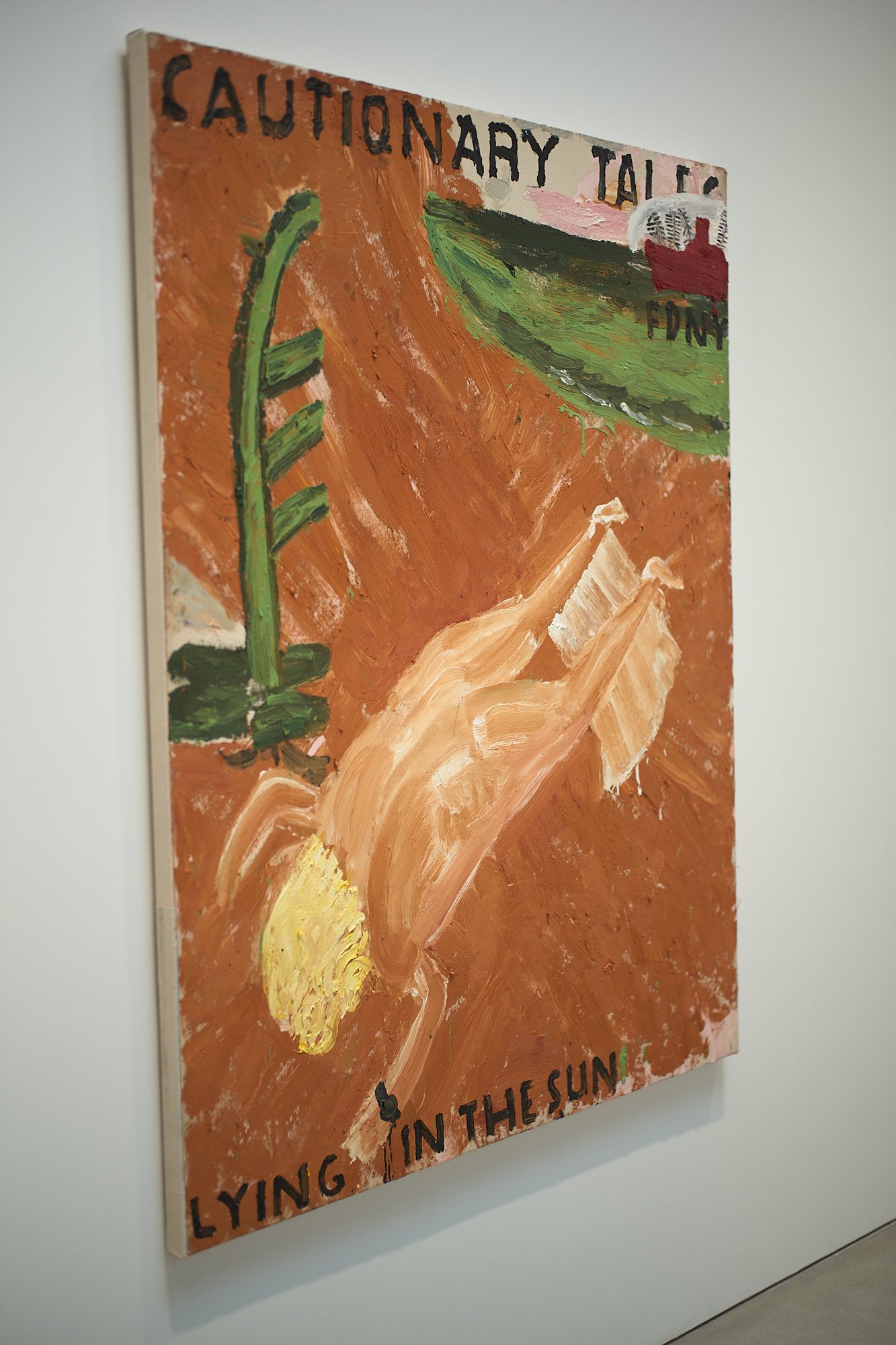

Derek Aylward Good Morning Sunshine

Rose Wylie: CLOSE, not too close

Jenny Holzer - READY FOR YOU WHEN YOU ARE

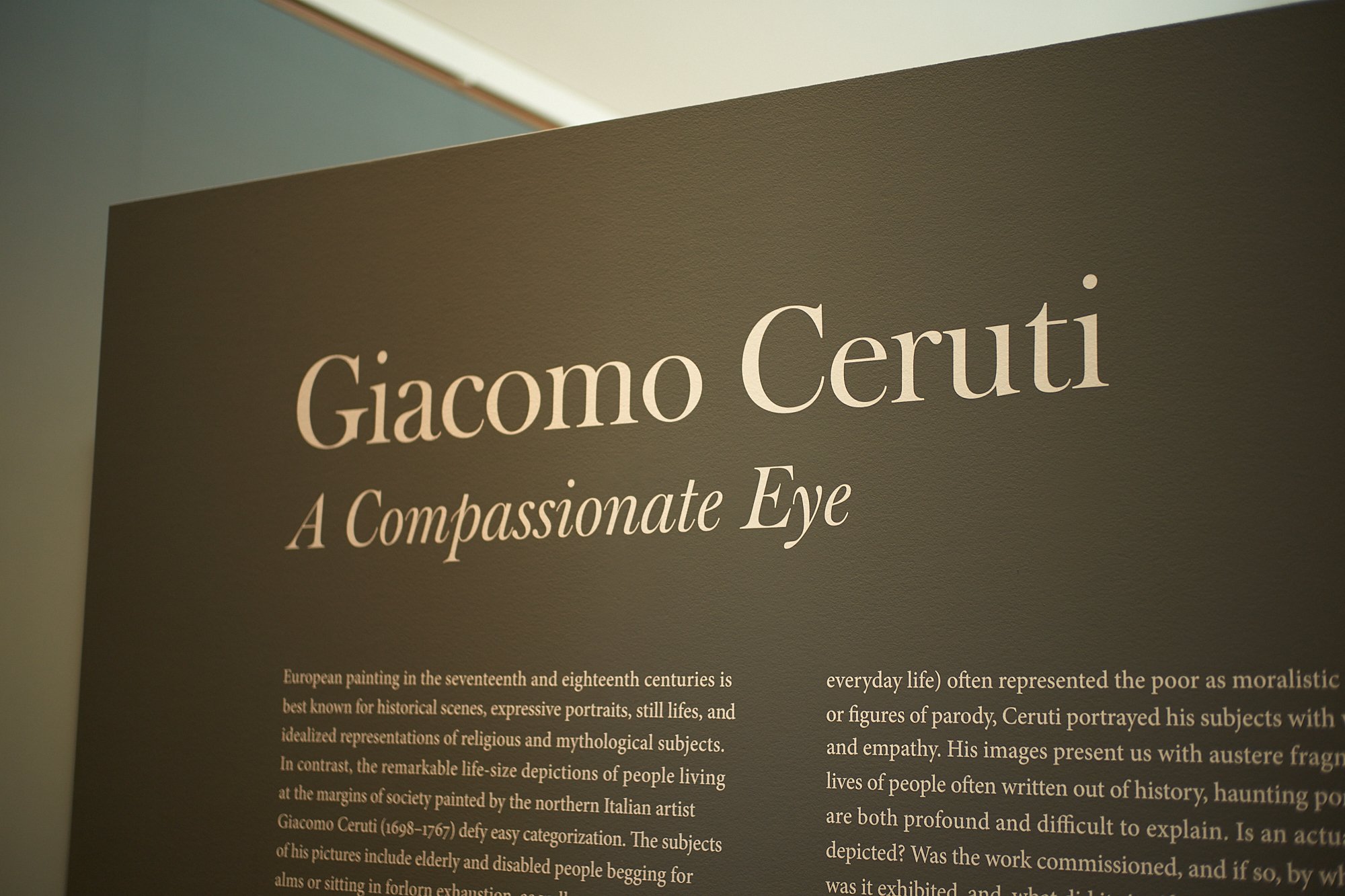

Giacomo Ceruti - A Compassionate Eye

July 18–October 29, 2023, GETTY CENTER

paintings by Italian 18th-century artist Giacomo Ceruti, beggars, vagrants, and impoverished workers are portrayed in mesmerizing realism, emanating a sense of dignity and emotional depth.

Bertrand Russell

Interview: Jon, Ho.listic Operations

Balse:

So I have known you for a few years now, meeting you at the farmer's market weekly. I have been quite interested in your story. And the more I know about what you're doing, I just thought it would be great to do an interview. So the company, the project that you're working on is called Holistic Operations.

Jon:

Holistic, yeah. Ho.listic, yeah.

Balse:

Ho.listic, okay.

Jon:

Put the dot in there. Separate my last name from the rest of it.

Balse:

Okay, so it's ho.listicoperations.com or?

Jon:

Yeah, Ho.listic Operations is kind of the whole thing, because Holistic was kind of, I think, too vague and I couldn't find a website with just holistic. So I try to use... My last name's Ho, right?

Balse:

Oh, that's what it is.

Jon:

Okay. So then the Ho, that Holistic, and then the operations is also another O. So the first letter, Holistic, and then operations is also an O. So I just try to throw my last name in there, maybe a little too much to add my personal touch to it.

Balse:

I love that. I like that. Okay, so please state your name.

Jon:

First name Jonathan, last name Ho. My friends in high school used to call me Ho.

Balse:

Oh really? Yeah. Too many Jonathans.

Jon:

Yeah, exactly. Ho's is shorter, too. A lot easier.

Balse:

Okay, I see. And so you do micro-

Jon:

Greens.

Balse:

... greens. Microgreens out of your garage where we are right now. And we're sitting in the midst of your greenery.

Jon:

My workspace, my beet laboratory, my everything.

Balse:

And we are in, I guess it's Koreatown.

Jon:

Like the mid-city area.

Balse:

This is of grandma's? Your grandpa's or?

Jon:

Yeah, my grandparents used to live here. I grew up coming to this house as a kid, spending holidays here with my family, and then my grandparents ended up moving a few blocks away.

Balse:

Oh, really? Okay. Oh, so they're still...

Jon:

Yeah, they're still here. Well, with an asterisk as well as the elderly folks are.

Balse:

Yeah. I see. And this is the detached garage?

Jon:

Behind the house.

Balse:

And this is your operation, Ho.listic Operations. So you do vertical resources engineering?

Jon:

No, vertical farming.

Balse:

Vertical farming. That's what it is.

Jon:

Taking advantage of basically multiple planes in the vertical orientation.

Balse:

Yes. So if you could tell me about hydroponics. I understand...

Jon:

What is it?

Balse:

Yeah, what is it? So for those that do not know.

Jon:

Hydroponic simply is just an alternative farming method where technically anything that doesn't use soil would be considered hydroponics. Whether you use a fibrous medium, you could use clay pebbles in certain applications, you can use a fibrous paper, fibrous fibers, basically anything without soil. And then you use a water, the nutrient-based solution where you have water, you add nutrients to the water, and then you basically feed the nutrients directly to the plant root zone exactly.

Balse:

And in your case, do you use any fiber or just...

Jon:

I use these bamboo papers. Ba paper,

Balse:

Bamboo papers. Oh, interesting. I see. Have you tried something different too?

Jon:

Yeah, I started with soil before. The problem with soil for me was I'll get a lot of complaints about the grains being kind of dirty. Run a soil, what do you expect?

Balse:

Yeah, what do you expect?

Jon:

Yeah. And also when the trays get saturated and they're full of soil, they get really heavy, too. So I ended up breaking a lot of trays also. And when I first started, I really tried to really minimize the waste and stuff that I was sending away. And soil is just very bulky. So in terms of volume, it's a lot. And it gets really heavy, too. And I would try to compost most of the stuff here on site, but then as you get bigger and larger, you expand that total volume becomes kind of unmanageable, especially with soil, too.

So then I was like, I got to find ways to kind of reduce the volume and overall just mass, the waste that I'm trying to compost or sent to the industrial composting facilities. And soil is also not a very renewable resource either. Soil takes many years to form, and you've got organic material to break down. You need different particle sizes, whether it be sand, soil clay. It is a very long process to create soil, especially fertile soil, too. And I thought bamboo is one of the quickest growing biomasses in the world.

Balse:

Interesting, okay.

Jon:

Yeah. So it's like bamboo is kind of after soil. I was like, you know what? Maybe something like bamboo might be a little bit more conducive to what I'm trying to accomplish.

Balse:

I see, I see. So it's a combination of the efficient material and sustainable.

Jon:

Exactly, yeah. Just trying to be resource conscious. What are my inputs, what are my outputs? And try to keep those relatively in balance.

Balse:

I guess your whole concept is pretty fascinating looking at your website. Basically you have a short-term and long-term goal. Short-term is really, as you said, decreasing reliance on industrial farming.

Jon:

That could be a long-term one, too.

Balse:

I think just going to read on your site reliance on corporate farming while producing quality food.

Jon:

Exactly.

I mean from an environmental standpoint, large scale corporate farms are one of the biggest contributors to not only greenhouse gasses, but also pollution in general. You have to run off of these sites. Here in LA, helicopters are overhead every day. So you look at these large scale corporate farms, traditionally most of them are monocultures. They grow one crop, and it's not really, that makes your crop very prone to disease or pest, because if one crop is affected, the whole crop is the same and you get wiped out.

And also when you look at how they go about watering all the waste that comes off their sites and stuff, not only contaminates groundwater, but also air quality surface water as well. So that's kind of a big reason why I also try to do hydroponics as well, because you don't have any runoff really. And same with soil. In this application, there's no runoff really. But still, it's trying to find ways to really take the current challenges or problems with traditional farming and try to address those in a way, obviously on a much smaller scale, but still in a way that is feasible and also economical.

Balse:

I like the word you said, a word decentralizing.

Jon:

Yeah, decentralizing food production. I'm sure a lot of crypto guys would be like, oh yeah, decentralization all the way.

Balse:

I guess it is a key word lately, too. And then you have the long term, which is actually even further exciting, I think is...

Jon:

Exporting the mindset, the technology, whatever it is.

Balse:

Yeah, you're kind of learning by hand.

Jon:

Exactly. Learn by doing.

Balse:

Yeah. What is it called? Rolling up your sleeves, actually doing it yourself. Testing out different methods. And I'm sure it depends on-

Jon:

Location, climate, whatever.

Balse:

...location, too. But you're actually experimenting every day, researching, and you're kind of accumulating knowledge around actually doing, not just philosophizing.

Jon:

Exactly, yeah. Making it practical instead of moving from the theoretical now to the practical. Because that's kind what got me started too, is seeing how most of the world lives not in a very practical way, is based off primarily necessity. It's unfortunate, but if they have avenues or ways that they can do things a little differently, that's probably more beneficial to them. Versus the people that are buying their product, which tends to be large scale corporations, whether they be agricultural feed, commercial fertilizers, whatever. There's got to be ways that we can decentralize that from the people and have them more, I guess, work in their own best interests versus another no face, big name company that tends to take advantage of these impoverished people.

Balse:

So you kind of came to this through your direct experience traveling and well, I understand you studied, what did you say?

Jon:

Engineering?

Balse:

Farming tool and then water resource engineering. And was it during school or after school you went to Southeast Asia?

Jon:

So the first time I went there was after I finished undergrad, I forget the exact time. I think just after I finished undergrad and before I was working, and then had the opportunity to go do some consulting, I was offered a position to go overseas.

Balse:

Okay, so it was part of your job when you went?

Jon:

No, it was a completely different job. Completely different. Before I was doing solar. I was working in solar, so I've always kind of been ingrained in the environmental aspect of things, whether it be energy, whether it be farming. To me, it was like farming, manufacturing, and energy production. Those were the three big, I guess, contributors to the environmental problems that we face. And me by myself, I'm like, man, manufacturing, I don't have a factory to make things. So that one was kind of out of the question for me.

And then so energy production, I was like, okay, there's a lot of solar companies around to see if I can inform homeowners, the general public of some of the benefits. And then that's when I really learned about all the stuff behind the scenes, whether it be the local, the federal incentives programs that they have available for homeowners. And then kind of how solar companies operate within that sphere. You know what, it's a business, you're not really in it for the environmental aspect of it. More so just signing up people with sales, close them, sign them up, get it installed in their house and move on to the next one.

Balse:

It completely really, I don't know, maybe the corporate initial vision may have some environmental aspect maybe, but it's very much driven by profit, of course.

Jon:

Exactly. Yeah, exactly.

Balse:

It's very industrial...

Jon:

Not to say that I'm not either. I'm not going to say I'm the shining knight in white armor.

Balse:

Yeah, I see. So you saw that side of it, but wait, can I step back then? What actually initially drove you into that interest in the environment and sustainability in general? Because you actually chose that as your major, right?

Jon:

I fell into it accidentally. I would say that in high school, that's kind of where it started. And for me personally, I wasn't the best student. I was always relatively smart, and I never really had to try that hard in school. So I found myself kind of bored sometimes. But it was my environmental science class where I really kind of piqued my interest, hey, this whole world, the earth that we live on is a giant system that we exist within. And we obviously alter the environment in many ways, obviously many ways to our benefit and also to our detriment as well.

And I just found it interesting how people have modified the earth for better or for worse. And I just found it interesting how we can collectively have an impact and affect climate, affect water quality, air quality, all these things. And then it wasn't until I got to college where I initially got into Cal Poly as a horticultural major, environmental horticultural science, which is horticulture is basically the study of plants. And then for me, freshman in college, I was like, man, what the heck?

Plants, I never really connected all the dots, plants, environments, all these things. I was like, plants are cool, but I want to do something a little... I'm from an Asian background, I was like, you know what? Maybe this is not the best route to make my parents and my family proud. Maybe let's switch to something a little more technical. So then I went to environmental science, and that's where I kind of got a broader picture instead of just the plants. I was focusing on water systems.

Balse:

You mean you changed your major or just...

Jon:

Yeah, I did my major my sophomore year. So from environmental horticultural science to not just environmental science, a broader aspect of it. And then I focused on hydrology, and I was really just fascinated about how water really carves landscapes really is the lifeline, the bloodline of most productive areas. You need good quality water and you need water to sustain life.

Balse:

Yeah, I mean most historical civilizations...

Jon:

Exactly on rivers along waterways. Yeah, the Romans built incredible aqueducts to transfer water closer to them.

Balse:

Or even as we speak right now, we wouldn't be here if we didn't have our LA aqueducts.

Jon:

Yeah, exactly taking water from the north or the Colorado River and bringing them to us. Otherwise we'd just be a desert here in LA. So I was really fascinated about the larger picture. And then obviously the horticultural stuff came after I finished all my school, my master's, and everything. I was like, you know what? Maybe I'll revisit that. And then I found, man, people have created a symbiotic relationship with plants as well, whether it be ornamental plants like flowers, shrubs, bushes, and also the edible plants, greens, leafy greens, fruiting plants.

Humans have left such a large imprint on the world. And I was just so fascinated by that aspect of it. Man, we can have such a large impact, which typically tends to be a negative one from an environmental aspect, but small steps, baby steps to make bigger beneficial changes over time. I was like, man, okay, that's really interesting to me.

Balse:

So you switched your major to environmental science?

Jon:

Exactly. Science is undergrad, and then for grad school, then that's where I've kind of pursued in an even more technical field of engineering. Let's do calculations, let's engineer channels for water.

Balse:

This is civil engineering.

Jon:

Exactly.

Balse:

More bigger projects and stuff.

Jon:

Exactly.

Balse:

Building stuff.

Jon:

Exactly. Bridges, culverts, water treatment plants, wastewater treatment plants, all these things.

Balse:

Before you went to grad school, you worked, right?

Jon:

Exactly. I worked a little more. I was doing environmental consulting. So basically before any kind of construction goes on in a building, we need to do site assessments, evaluate what is the current condition of the land that we're going to build. If you want to put a residence on top of a piece of land, you want to make sure that there's no contaminants in the soil, whether it be volatile chemicals, benzene that will kind of disperse into the air over time, or hydrocarbon gasoline, diesel, which can also have negative impacts long-term on people or residents who inhabit that land.

So that's what I was doing before, consulting, kind of getting my hands dirty. Again, different sites, doing soil borings, seeing what's in the soil, and then finding ways that we can remediate it. If it's volatile, we kind of just excavate the site, ship that contaminated soil offsite to a hazardous, depending on what the nature of the waste is. But typically it'd be like a hazardous waste or generally just a landfill in general.

Balse:

Very technical stuff.

Jon:

Yeah, definitely.

Balse:

Basically putting up reports for the client.

Jon:

Exactly. What did we find? What do we do to remediate it? And then what is the final, I guess after our job is done and we've remediated the site, making sure, providing data to say that, "Hey, we've removed all the contaminants and now these are the numbers," to say that whether it be a gas vapor to probe that can measure the emissions of the soil to say, "This was the initial level, and this is after all the remediation. It's basically down to zero or below the ESLs where the safety limits basically."

Balse:

I see, environmental safety limits.

Jon:

Exactly. Pretty much. Yeah.

Balse:

I see. And the clients are usually like-

Jon:

One that I was doing exactly with the builders

Balse:

Or the government?

Jon:

No, it was more private. It was more private, but we would've definitely had the city come by, inspect and stuff, too.

Balse:

Oh, it's more like the city inspecting. You want to nature that, the [inaudible].

Jon:

We were working for the, I guess, the landowner essentially. They hired us to come on and do the site assessment and then take care of the problems that we, I guess identified.

Balse:

I see, I see. So that was the corporate job?

Jon:

Yeah, that was probably the solar one was definitely a lot more corporate. The consulting definitely had that corporate feel to it, but I was working for a small consulting firm, so it didn't have all the politics going on and stuff. But still with the landowner, the foreman of the site, the city coming in, just trying to play politics between the different parties, all the moving parts. I'm like, okay, this is a fascinating kind of.

Balse:

Yeah, I see. And then so you did that for a couple years?

Jon:

I did that for a year. And then I was like, you know what? I've learned a lot here and I think I've kind of got a pretty good general grasp of the process and everything else that goes along here. And then maybe just go try to see something else, see what else I can learn, and how else I can maybe add to my experiences. Because I'm just going to basically go off of my education instead of experience and also personal philosophy. So how can I continue to evolve that philosophy and maybe tailor it more to a way where I feel like I'm having more of an impact

Balse:

Or aligns better.

Jon:

Exactly. Yeah.

Balse:

And so wait, so that was then you go to grad school or you went...

Jon:

Yeah, then I went to grad school after that.

Balse:

So you decided to go to grad school, and that's civil engineering, the more hardcore stuff for a year or two.

Jon:

Exactly.

Balse:

I see. And then you have this, I guess, part of your job afterwards or something that you go to Vietnam or something.

Jon:

Yeah, I've been there several times. So I went there again after grad school too, and that's where I kind of had a better understanding. I was able to work with other people in the industry. So I worked with Dr. Zang. It's been a while since I've talked to him, but he's a professor. He's a professor now in China, but he at the time was associate professor over at Princeton. So it was me and him over in Thailand. And I had met some friends there previously that could speak decent English and help translate for us because neither of us could speak Thai. So we kind of just toured around the province that we were in, visiting different sites.

We thought that we kind of identified on maps before in key areas, in the key areas of the watershed, higher up in the watershed, kind of more in the floodplain area, and more down south where all the confluence of the different rivers and streams kind of discharge into this one southern region where instead of farming, they're now doing more fish aquaculture. So more farming of fish instead of plants. So you see the different aspects around the province and how they're affected. And they're all kind of related in this way. They're kind of connected by the water. And the further south you go, the more I guess territory the water flows through, you find that the more contaminated it becomes. Kind of just converges and accumulates in this one point. And it was eye-opening to me to see how this is how people live? Oh my god, this is a totally different world from my life.

Balse:

You go downstream.

Jon:

All over. All over.

Balse:

Oh, I see. Upstream as well.

Jon:

And just totally different to what I was accustomed to here.

Balse:

I see, so more culturally and everything. I'm talking about just the degradation or anything.

Jon:

Exactly, lifestyle and everything. And also the lifestyle is affected by the degradation of the environment as well, how they have to continually adjust and do things on the fly. So even though these people there aren't really formally educated, they're still incredibly resourceful and able to... Obviously there's a cap to what they can do, but you can see them in real time just trying to make changes of what they see. They understand the land very well. They've worked in these areas for generations. Great, great, great grandfathers lived off the land and they've been doing the same thing for generations.

And it's just kind of crappy now that the government in Thailand has stepped in and said, "Oh, you know what? We're going to make any work or habitation in these areas illegal." But I was like, man, these people have lived here for generations. You expect them to leave, vacate the area, and do what now? Go to the city and find a job. And it's like, but there's a million plus people in these hillsides here that live off the land. It's like they're all going to go to the city and find some kind of skilled work that can pay them a decent wage and help them make a living? Some of them will make that transition, but the vast majority will probably not make that.

Balse:

So the government's trying to do...

Jon:

So the government is aware of the environmental crisis going on there. So that's why their answer or their remedy, I guess would be to get the people out of there, and remove them.

Balse:

The whole problem is the way the people do agriculture.

Jon:

Exactly.

Balse:

Burn down.

Jon:

Exactly. Slash and burn.

Balse:

Slash and burn, right.

Jon:

Exactly. So work one parcel of land for a season and then kind of move on to the next. So you basically exhaust the soil's nutrients in one growth cycle, move to the next. And if you want to stay on that same plot of land, you would have to spray. And they do end up spraying most of the time anyways, to kind of combat pests, other diseases like fungus and stuff.

So yeah, the way they currently go about it is slash and burn, heavy use of synthetic chemicals, fertilizers, herbicides, fungicides, and then they move on to the next plot. So it's interesting, when you fly in, my first time flying in, I had no idea. I was looking out the window from the plane looking down onto these mountains. They're like, man, these mountains, some of them are dense, lush forests and other ones, they're just barren, brown, bare soil.

Balse:

After the slash and burn.

Jon:

Exactly. So you just see the dichotomy between the two. Holy cow, that one looks not good, not productive, nothing on it just bearing death. And the other one is just full teaming with life. You see the contrast. And over the last 10 years, it's been like, what, 15, 16 years now. But my first time there, what I've learned was that over 10 years, they basically cleared a third of their forest. And man, and there's a lot of forests. And in 10 years you guys did this much, holy cow. And that's probably a product of raising the cost of living for the people. Maybe they're exposed to other parts of the world where they see people have technology, other ways of living. They're like, wow, okay, now we should expect to have this for us. We got to make more money.

And also the agricultural companies that they would sell their product to is primarily just corn, cutting down the forest to grow things on corn on the mountains and to say, this doesn't seem a practical or sustainable solution long-term. So the problem a lot of these farmers would face is that these ag companies that they're selling their product to are also the ones that are loaning them money and equipment. So these companies know exactly how much they lent out to farmers at the beginning of the season. So at the end, come harvest time, they can undercut them, say, "Oh, we'll only buy your product for this much." So you kind of keep these farmers in a cycle of debt where they have no choice but to keep doing what they know how to do.

Balse:

Exploitation.

Jon:

Exactly. If you're in this position where you feel you have a boot on your neck, on your throat, you're not really going to be incentivized to kind of try to do things differently, try something new. You're going to stick with what works. We know how to do this, let's just do this. Instead of trying to venture out and try something maybe more creative or something a little bit different. So it keeps them kind of trapped in that sense. And it's just unfortunate. It's like, wow, we have to find ways to get these people, give them access to whatever information, resources, whatever it may be to help them improve their situation.

And that's what really inspired me to see how hard these people work and just how genuine they are. You go out there, you talk to them, you meet them, they're so hospitable, they welcome you with open arms. They're willing to talk to you about whatever they're facing, the challenges, what they're doing, all these things. And at the end of the day, they're just people too, just trying to make a living, feed their family.

Balse:

Yeah. I think I saw one of the photos on a webpage and about the section. Is Ms. Professor Zang in that picture?

Jon:

He probably is. He probably is. Yeah.

Balse:

I'm guessing he's a pretty young guy.

Jon:

He's young. I think he was a little older than me, I think maybe a few years older than me.

Balse:

Oh, I see. Now I clicked. So I noticed a few people with you.

Jon:

Had a little team out there.

Balse:

I see. And the thing is that it's similar, that's like one sample that you actually hands-on saw and multiple times over the years in Thailand, but that's happening in Amazon, everywhere.

Jon:

All over the world, exactly. South America, Southeast Asia, Central America, Africa, everywhere, all over the world. We were being exploited for their natural resources, unfortunately.

Balse:

So all that, having experienced that, seeing that and with your background and interest and your engineering background, you came to... Or you were constantly thinking about, okay, how can you solve or what can I present as a potential solution and come to this vertical farming.

Jon:

Exactly. It was a combination of just education, my experiences in life and what I'm seeing and work as well. How can we find ways to help these people? Obviously they're kind of forgotten, unfortunately. And for me, when I'm out there, I'm like, man, these people are so good and understanding, reading the land. And they obviously don't want to cut down the forest because what can they do? They're not skilled in the traditional sense where they'll pick up a computer and go learn C++ or Java or whatever, HTML. And that's kind of the direction that a lot of nations tend to be headed. We're in a more tech-centric economy, and these people are kind of getting left out in the dust.

So in my head I'm like, man, these people are so good with growing things, understanding the land, harvesting time, weather, and all that. They're so incredibly smart in this regard. Maybe we can channel or utilize their current skill set, but maybe in a different environment where they don't have to cut down the forest. If we were able to maybe use less land with vertical farming, move them indoors, find ways to get donors or sponsors. Because my boss at the time, that was kind of his idea was we can get donors or sponsors to help the farmers here. But then I was like, "We'll help them, how?" We got to have a direction and a direction to go towards. You're just asking for donations, people, "What's my money going to go towards?" Well, helping the farmers, helping the people, we'll help them, how?

So in my head, I'm like, well, one way would be we could build little warehouse spaces where they can do large scale vertical farming. They can come together collectively, bargain and all that, pool their knowledge and their resources together and do farming what they already know how to do, but in an indoor setting. So then I started, when I came back, I was like, you know what? This has really inspired me to try to figure out what the challenges are. I'd never really grown things before. I had grown basic things, basil before. I just threw the seed out there, it grew, oh wow. It grew. Oh my gosh, this is incredible. But I didn't really think of it beyond that.

But after seeing these people working the land, I'm like, man, okay, this is mind-blowing to me, man. Got little Asian ladies that are basically propagating an entire mountainside of hillside rice one at a time. And I'm up there and you look, the whole mountain is rising. I'm like, this one lady did all of that herself in this near vertical slope. I'm standing up there, I might slip and fall myself, and she's doing this. It is no big deal. Oh my gosh. Holy cow. These people are so resilient.

So then I started, I came back and I was like, man, I want to find ways to really understand better and do it myself because I went to Cal Poly. The motto for both of them was learn by doing. And they're very hands-on in that regard, so that's how I really kind of started. I found that what I learned best also was hands-on. So then I came back, I was like, you know what? I'm inspired now. Let's see what I can do here. I started doing aquaponics, which is combining fish and plants. So the fish-

Balse:

Oh, the definition of aquaponics has a fish side.

Jon:

Exactly.

Balse:

I forgot about that.

Jon:

Aquaculture would be just fish farming, just raising fish. And then hydroponics would be growing plants without soil.

Balse:

You combine the two is aquaponics.

Jon:

Aquaponics, exactly. So now you use fish, the fish will poop and pee in the water.

Balse:

They'll create an ammonia cycle.

Jon:

Exactly. You basically take the natural system and kind of put it in a more man-made controlled system in a way. So the fish will basically poop and pee in the water, create ammonium in the water, and then you have nitrogen fixing bacteria in the water. So those bacteria will convert the ammonium to nitrate, which is the usable form of nitrogen for plants. So then those bacteria microorganisms will convert the right ammonium to nitrate, send that water to the plants, and the plants will then clean that water, send it back to the fish. So it's a closed loop system of cycles. And to me, conceptually, I was like, this is incredible. Oh my gosh, this is the future.

And I started doing it and I'm like, man, this is challenging. Not only do I have to worry about the plants, I have to worry about the fish. The water temperature gets too low, the fish will die. It gets too hot, they'll die. pH water balances get up, they'll die. I find myself to keep adding different, supplementing the water. I don't expect these villagers or farmers or people who are affected by this farming crisis in a way to really-

Balse:

It's not manageable.

Jon:

... uptake water quality and water chemistry even. That's what I studied. I'm like, man, I had to go through school for this. Do really formal education to understand the alkalinity in the water, pHs and all that. This is probably going to go over the heads of most of these people. They're going to be like, you know what? Why am I going to do all this extra stuff when what I'm doing now is not great, but it's working okay.

Balse:

So you did initially the ideal goal was do the aqua-

Jon:

Aquaponics.

Balse:

... ponics, but you kind of quickly found out that it was too complex, not feasible, it's unmanageable-

Jon:

And trying to scale it to...

Balse:

... scale.

Jon:

You have to have huge water tanks, copious amounts of nitrogen fixing bacteria, membrane filters, and all that. This is technically, it's amazing, but practically it's...

Balse:

Conceptually it's great. It is a wonderful but utopian kind of...

Jon:

Exactly, yeah. Not to say it can't be done. It comes with a lot of challenges, a lot of a very high initial startup investment. And then also for me, I didn't really have a whole farming background. I started growing in my system. I had bok choy, gai lan, all these different Asian vegetables, and they started well at first. And then once I found out that spring's coming, the caterpillars and the bows that come out one day just caterpillars everywhere. I'm like, oh my gosh, I just waited like five, six weeks to get to this point, and now everything I've done is now null, basically trashed. And I'm like, oh my gosh.

So there must be a way other plants that can grow quicker that don't need as much time maybe, that maybe will not be as prone to this pest issue. I don't want to be spraying things to kill the caterpillars. And initially it was kind of cool. I was like, oh, caterpillar here, feed it to the fish, caterpillar, to the fish. I was like, it's totally, totally a closed loop. I don't even have to feed the fish, give them the caterpillars to show up. But over time, it becomes unmanageable with all... As they get bigger too, it's like, man, there's caterpillars everywhere. I've got to see under every single leaf to see caterpillars.

Balse:

I see. Starting to see how quickly...

Jon:

How to scale, it adds up over time. I was like, man, this is a lot of work. So then I stumbled upon microgreens. I'm like, man, what do you mean you can grow things in like 10 days?

Balse:

How did you stumble upon that?

Jon:

I just started doing more research

Balse:

Just online?

Jon:

Yeah, more research and try to find things that instead of aquaponics maybe I'll just do hydroponics now instead, kind of simplify it a little way, keep it simple. And especially if we want people to adopt it widely, the simpler it is, generally it'd be easier and more people are more willing to accept it. We have all these obstacles and all these hurdles in the place. In the beginning they'd be like, you know what? Maybe a cool idea, man, but we'll think about it later. So if I could simplify it in a way, I felt that that would be maybe more digestible. Aquaponics takes a bit more space, too, because you need the fish tanks, the biofilters, the biomembranes and everything and all that.

Balse:

Which means more investment.

Jon:

Investment, exactly. More investment. Exactly.

Balse:

That's technical.

Jon:

I found out about microgreens. I'm like, holy cow, this is incredible. I don't need all the moving bed biofilters or the beads in them and everything. I don't need the fish tanks.

Balse:

But you're doing that here though?

Jon:

I was actually doing that at my parents' house.

Balse:

Aquaponics.

Jon:

Aquaponics. So I had it in our side yard, and it's also super noisy because you have to have an air pump going all the time. I had maybe a one gallon or something. I forget the exact air pump that I had, but you could hear it going all day, all night.

Balse:

So electricity.

Jon:

Exactly. Electricity. A much higher cost, operational cost as well. So then microgreens, I found out what those are, started growing those.

Balse:

Were you actually selling at that time?

Jon:

No, I wasn't selling. I couldn't even get a product too hard because the caterpillars and the bugs and everything, just getting to them before I could even harvest them.

Balse:

So just purely experimental. Recent development phase.

Jon:

Exactly. And then after I shot away from that microgreens I'm like, man, 10 days, 12 days, 14 days. This is incredible. And that's when I started, okay, now I can see something here. There's something here.

Balse:

To grow, from planting the seed to harvest 14, 13, 14.

Jon:

Exactly. Yeah. Depending if it's warm out, you could do 10 to 12 days.

Balse:

That's crazy.

Jon:

As it gets a little colder, maybe 14 days or so, but still much faster than your traditional microgreens in a sense where they're more mature vegetables. And then I started doing more research and I found out that microgreens are actually much healthier, too. So I'm like, man, less water, less time, less land, more benefits. This seems to be the way. And then I started going, now I shifted from aquaponics now fully into microgreens, hydroponics.

Balse:

Hydroponics.

Jon:

So I'm like, okay, this to me seems to be the future, not the only way a subset or an avenue for the future.

Balse:

Well, I think what's fascinating about this story is that I'm sure there are a lot of... I'm sure there are other people who are doing hydroponics and thinking about these things, but you are the ultimate long-term goal of combining the social aspect. To replace, how do you transform the way of life of the people around the world with this technology. Well, the way of agriculture and solving multiple kinds of problems at the same time. And this even the health problems.

Jon:

Yeah, exactly.

Balse:

And I think I personally think, and I'm all for it, and I'm really for all this and really want to support this idea.

Jon:

Appreciate that.

Balse:

I think one of the things I would love to see was this to be really successful and you're like...

Jon:

Appreciate that, thank you.

Balse:

And that success looks like you have more people actually... Basically, I think really, I think you were telling me that eventually you're maybe going back to the consulting and spreading this, doing more presentations and actually implementing this around the world. You might be actually consulting with some governments around the world or-

Jon:

Hopefully, yeah.

Balse:

... environmental organizations or...

Jon:

NGOs, whoever.

Balse:

And local communities, and actually making that transition, which will have a social macro impact.

Jon:

Definitely. Definitely. Exactly. Yeah, I echo those sentiments 100%. And do I have an exact timeline of when that's going to be? No, I think I'm entering the phase where I would consider myself now an expert at microgreens, at least I am growing them. Am I an expert at all the nutritional benefits? What do beta care teams do in the body? No, I'm not there yet.

Balse:

Do you do a blog or something or do you...

Jon:

I do not.

Balse:

You do not. I was thinking-

Jon:

I'm thinking about it.

Balse:

... maybe you should. Well, it's a matter of time but I think a lot of people would be fascinating, myself included-

Jon:

I hope so.

Balse:

... on your daily or weekly, whatever struggles and challenges and how you overcome... I mean, you already have such a hands-on... I'm sure you can go on and on about all the stuff that you've experienced, but that kind of daily small inches.

Jon:

The daily grind.

Balse:

Yeah, daily grind, one step forward, two step back, two step forward, and one step back kind of. It would be fun to see. And I think a lot of people will connect and will be willing to spread the word and support.

Jon:

I hope so. And I've definitely been thinking about that a lot myself. How can I maybe broaden the reach of what I'm trying to do? I bought a camera and obviously it is like, man, I got to figure out how to use a camera. What are good shots? How do I frame this? What kind of lenses do I want to use? I'm like, oh my gosh, this is a whole another rabbit hole for me to go down. I'm sure you understand that being someone who's kind of technically minded, you want to fully understand something before you-

Balse:

The uniqueness of it.

Jon:

Exactly. It's my weakness for sure. I want to fully understand all this. I'm getting into it. What kind of sensor size, a full frame, maybe APSC? Oh my gosh. It's a lot. Exactly.

Balse:

Well, I guess that's just the life of an entrepreneur too, I guess. Definitely a small business to grow, doing everything by yourself. But yeah, so I guess that's also the fun part of it, too.

Jon:

I do find a lot of satisfaction and fulfillment in that, too. How can I learn about different things every day? Maybe they're applied to my business, and I find that maybe that's not the best way to go, but I still learned about what that entails and what that actually is, whether or not it's applicable to me. In this case, maybe not always, but it's still fun to learn about new things. I kind of have that student mentality in that regard, but I just want to learn new things all the time.

Balse:

But anyways I'm just kind of thinking about how would you actually further drive this?

Jon:

That's also the challenge that I've been thinking about, too. I don't really have a good answer yet, but I'm always open to suggestions and other things, too.

Balse:

Because scaling yourself this and there's that side of it, but I think probably from a purely business, actually it's business as well as social impact. It's more kind of like a laboratory, you're actually doing, selling it directly to... You do the farm to table kind of thing.

Jon:

Exactly, yeah.

Balse:

Hands-on, but this scaling it as a company, that production side is one aspect, but I can kind of see it's much more scalable to do consulting or implement that system, spreading that system to the world. Anyways, okay.

Jon:

I think that's kind of what I'm trying to do now. At the beginning, I did have reservations. If I try to scale too fast, bring too many people on, maybe I'll lose the focus or what kind of brought me here in the first place.

Balse:

Yeah, I like that because I can see, it kind of goes back to that at the end where you are really valuing that social aspect of it, and not just kind of this word social. I mean, I guess more how we naturally should live kind of thing. The farmer's market, the world, the day of a farmer's market is truly that. You have this very kind of natural community.

Jon:

Community-based.

Balse:

Whereas immediately if you go to a Ralph's or a large Whole Foods or whatever-

Jon:

It's not intimate.

Balse:

... it's not intimate.

Jon:

You don't know who grew it, where it came from.

Balse:

It is all about efficiency. And it's all about how do you make a profit.

Jon:

Exactly.

Balse:

On the consumer side as well, how do you get in and out as quickly as possible?

Jon:

Exactly. Yeah. Save my time, save money, whatever it is.

Balse:

That's great. So here's the story I experienced on Saturday when I went to Wilson Park. There's this, I guess, a Greek vendor.

Jon:

Greek yogurt?

Balse:

Well, I think dips and stuff.

Jon:

Napa, the lady.

Balse:

No, not that one. There's a guy with a beard. I think he's Persian. Yeah, it's down towards the-

Jon:

The prepackaged side?

Balse:

Okay. Anyways, that's my go-to guy. And as I went there, there was a couple with a really young daughter, a small kid. And the kid was giving the vendor, him, I think it was like a stick honey or something.

Jon:

It was Catherine maybe.

Balse:

Yeah, so cute. And I was kind of patiently waiting, and then it was taking for five minutes so I kind of wandered around, but he noticed me I was kind of wandering and then went back him after. And the man's like, "Oh, thank you, sir, for being..." He knows me. He called me, sir, but, "Thank you for being patient." And I told him, "Well, no, no, no. This is part of the experience in the farmer's market, human connection." It's kind of like...

Jon:

That's my favorite part about the market, too. I really appreciate, and you take the time to get to know the people that come there to support not only me, but the other farmers that show up to try to provide some value to the community.

Balse:

Yes. I think it's a very kind of priceless-

Jon:

Experience.

Balse:

... a beautiful picture of that.

Jon:

Yeah, I would agree. It's definitely, that's my favorite part. I've only been doing it for two years at this point, but it's nice to see a lot of the people that come to support me, that shop with me, that give me their hard-earned money to exchange for what I have to provide. Over the last two years or so, I've definitely seen kids grow over the time and see how they tend to have maybe pique their interest in what farming or growing things entails, and it's very rewarding for me. My Friday market at Mimosa is not a huge market by any means, but that one is a lot of the kids at the school, after they get out of school, they come to the market.

Balse:

Oh really?

Jon:

And some of the parents will tell me, "Yeah, you know what? My child asked me for Christmas this year? They wanted a greenhouse and some grow kits and something." "Oh my gosh, please don't tell me that I had anything to do with that decision." But I can't help but think that maybe I had a little bit of input there. And it's very, to me, it's rewarding in a sense that you could have an impact beyond just the interaction and the exchange of goods and money. You could have an impact on their home life in a way, have them have things to converse about.

I really want to learn how to grow things now, so what do you think it's going to take to grow things? What do you need? Well, I'm going to need seeds and some water and maybe some soil or whatever it is. And it's nice to have that feel like you can impact not only the people directly around you, but also maybe future generations as well. Get them thinking about different things instead of always focusing on all I need is to just fit into a job and that's going to define me for the rest of my life. How can I have things as skills or interests outside of my work? That's why for you, I really respect and appreciate that you have a hobby and maybe something that you're trying to pursue outside of your work.

And that's how I felt too, when I was working before, I was like, man, this job is just defining me my day to day, sitting in traffic, driving up to Santa Monica every day. I like, oh my gosh, you look around you on the freeway. Everybody else is doing the same thing, too. I'm like, oh my God, we're all here on the same mission. Just trying to get the work, go home. I'm like, man, I've got to do this for another 40 years or 50 years? Oh my gosh, get me out of here. I'm just trying to find ways to really maybe get people thinking maybe a little bit outside the box or maybe about things that they may normally wouldn't think about or even consider, so it's nice to see that.

Balse:

What I thought about just now is your actually project name is Ho.listic. So going back to that example of Whole Foods and whatever the big...

Jon:

That's not the poo poo on them either. Exactly. They have a problem. They also provide.

Balse:

I go there all the time, and I appreciate that, too. I think what I thought was holistic versus compartmentalized. So the farmer's market experience is much more holistic and the whole concept is, the whole experience is that, starting with your directly producing agriculture, growing what you're selling. And you're actually seeing and experiencing the difficulty of that and just meeting somebody who's actually growing that for you. Whereas the other way, more urban and contemporary way is kind of dissected. It's grown by somebody and trucked by somebody in a warehouse by somebody, and then it's sold by somebody else. It's so disconnected.

Jon:

It is.

Balse:

You can't really feel, and of course, we're kind of social creatures, natural creatures, so you pick up on those things.

Jon:

100%, yeah. I think that's a big part about why a lot of people do choose to go to the farmer's market, too. That whole intimate experience where it's like, okay, this person grew this here, I get to know them, and you establish maybe some sort of trust within that person. It's kind of a relationship with that person versus what I was saying before, the Ralph's, the Whole Foods, not to doo doo on them, but it is a very kind of robotic experience. You go there, have everything's kind of sectioned off, and you just pick what you want and check it out and go home.

Balse:

It definitely, we do probably need both.

Jon:

We definitely need both. You can't get everything you need at the farmer's market either. And sometimes farmer's markets, you do have to pay maybe a little bit extra, so there also is that financial limitation that some people just can't access either.

Balse:

When I tell these stories to some of my friends, some people think that, okay, that's a very bourgeoisie. The people who can always purchase there, you have to be pretty wealthy.

Jon:

Have to have at least some semblance of disposable income.

Balse:

I totally get that, too. But at the same time, I think similar to what I said about I think what I want to see, what the vision of success for you, I think the vision of a successful society is where we have a much more kind of robust-

Jon:

Balanced, robust, yeah.

Balse:

... farmer's market, actually bustling farmer's market that's like a five times size of our farmers market.

Jon:

Oh, man. That would be wild. Yeah.

Balse:

That would be very exciting to see that kind of society.

Jon:

It would be really exciting to see that, where people take maybe more of an interest into maybe finding things that are maybe locally sourced. I think COVID kind of showed us this, supply chains can be fragile. If something happens, it's like, oh my gosh, we're relying solely on our supermarkets. Then it's like, man, you'll find that sometimes supply chains can be disrupted fairly easily, and then there's a lot of uncertainty around that, too. Not to say that the farmer's market is completely isolated if they're not either, but it's not going to be as bad, I think.

Balse:

It's more kind of like biodiversity. You have a more robust dynamic. If something goes wrong here. It's not the whole system's down, which...

Jon:

That's decentralizing the whole point.

Balse:

That's right. That's right, and that's how it used to be actually, because what some people say that the most robust and dynamic and resilient system is actually a pre-farming, which is hunting and gathering, which is basically you're not actually growing anything. You're actually relying on, what is naturally growing in the local environment.

Jon:

Yeah, we can't have 300 million people in America go out and go hunting for their own food. Maybe there'll be no more animals left. Hold on now, let's slow it down a little bit. Yeah, man.

A lot of things, interesting things to think about.

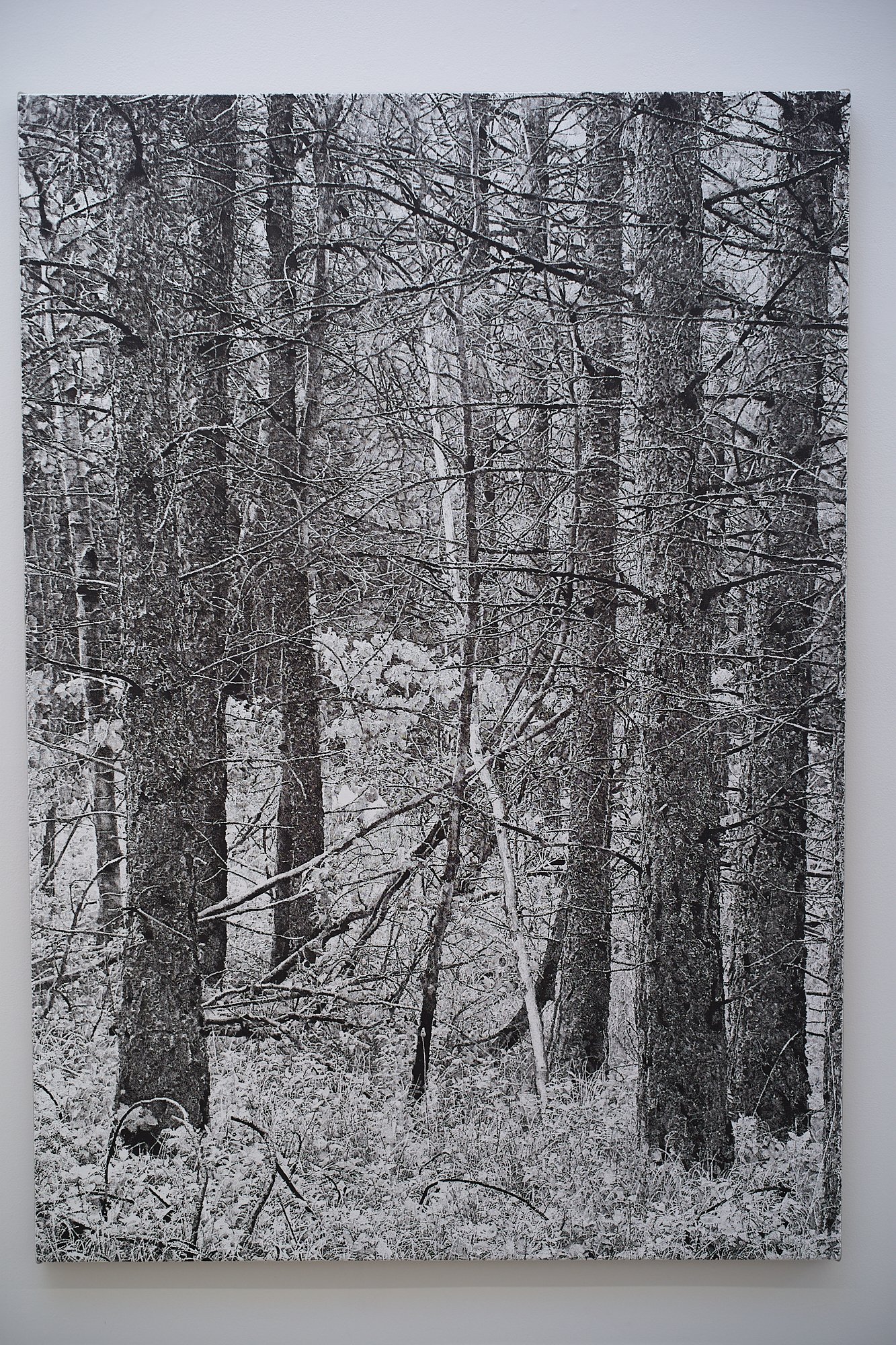

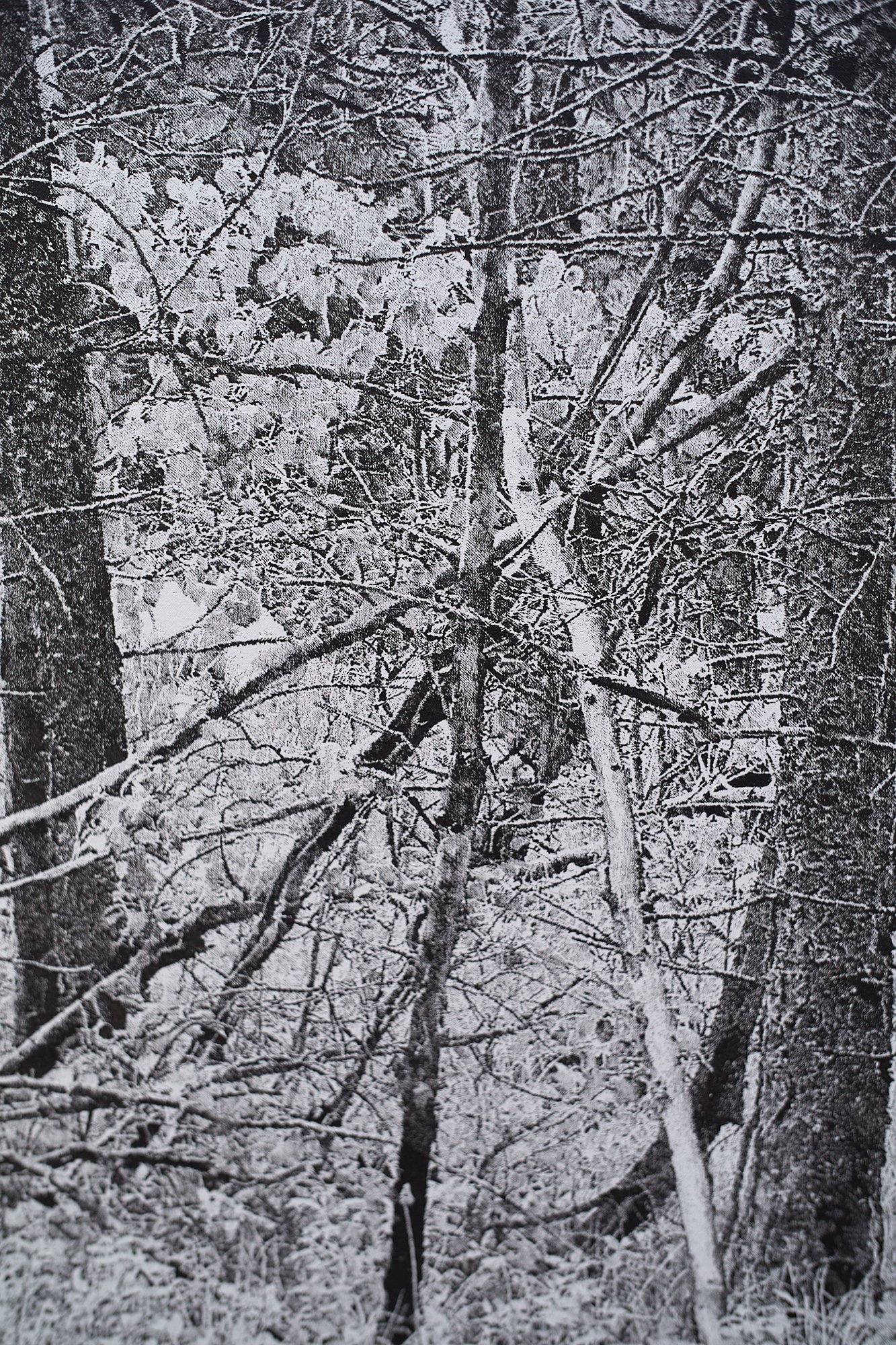

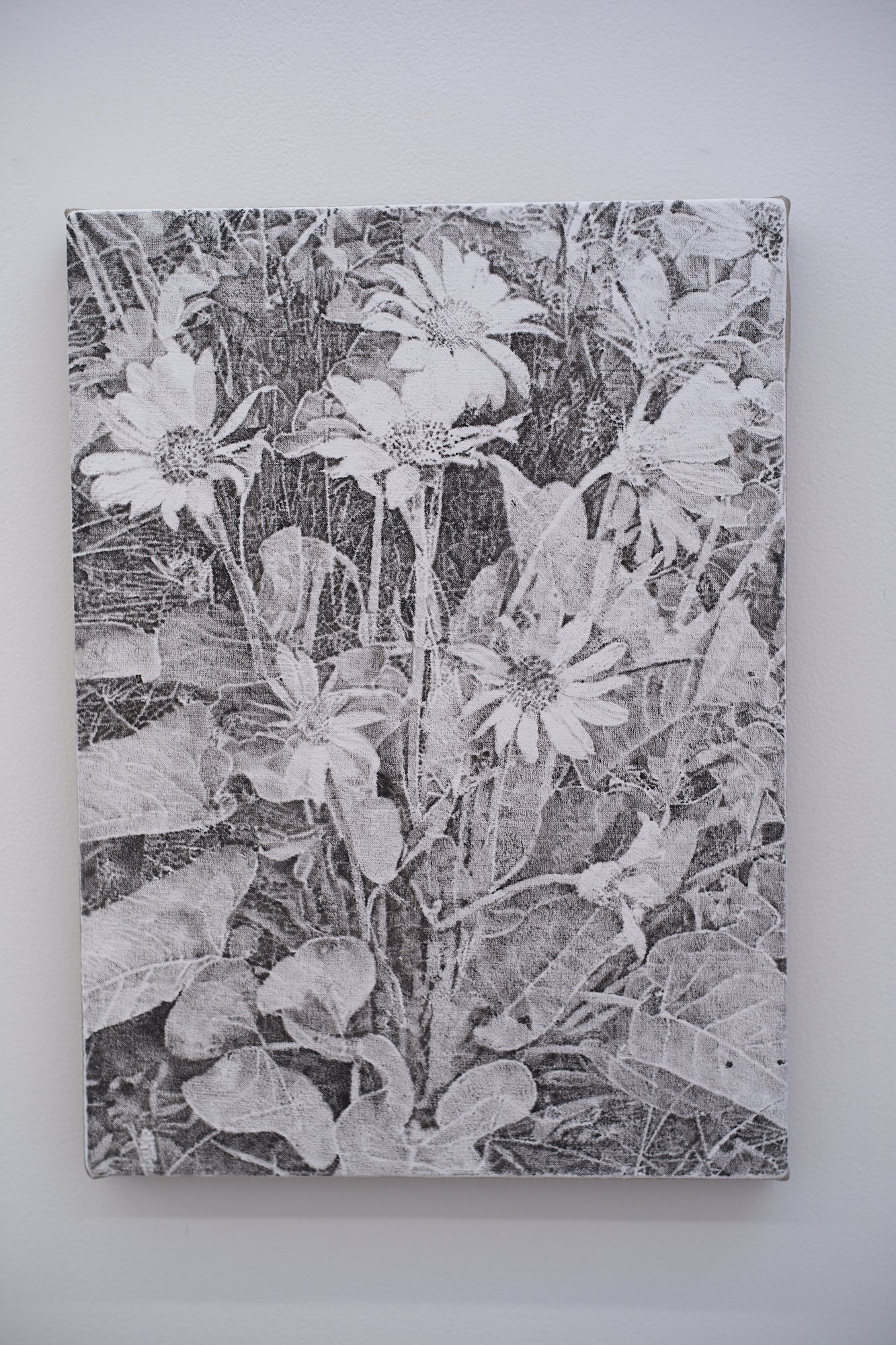

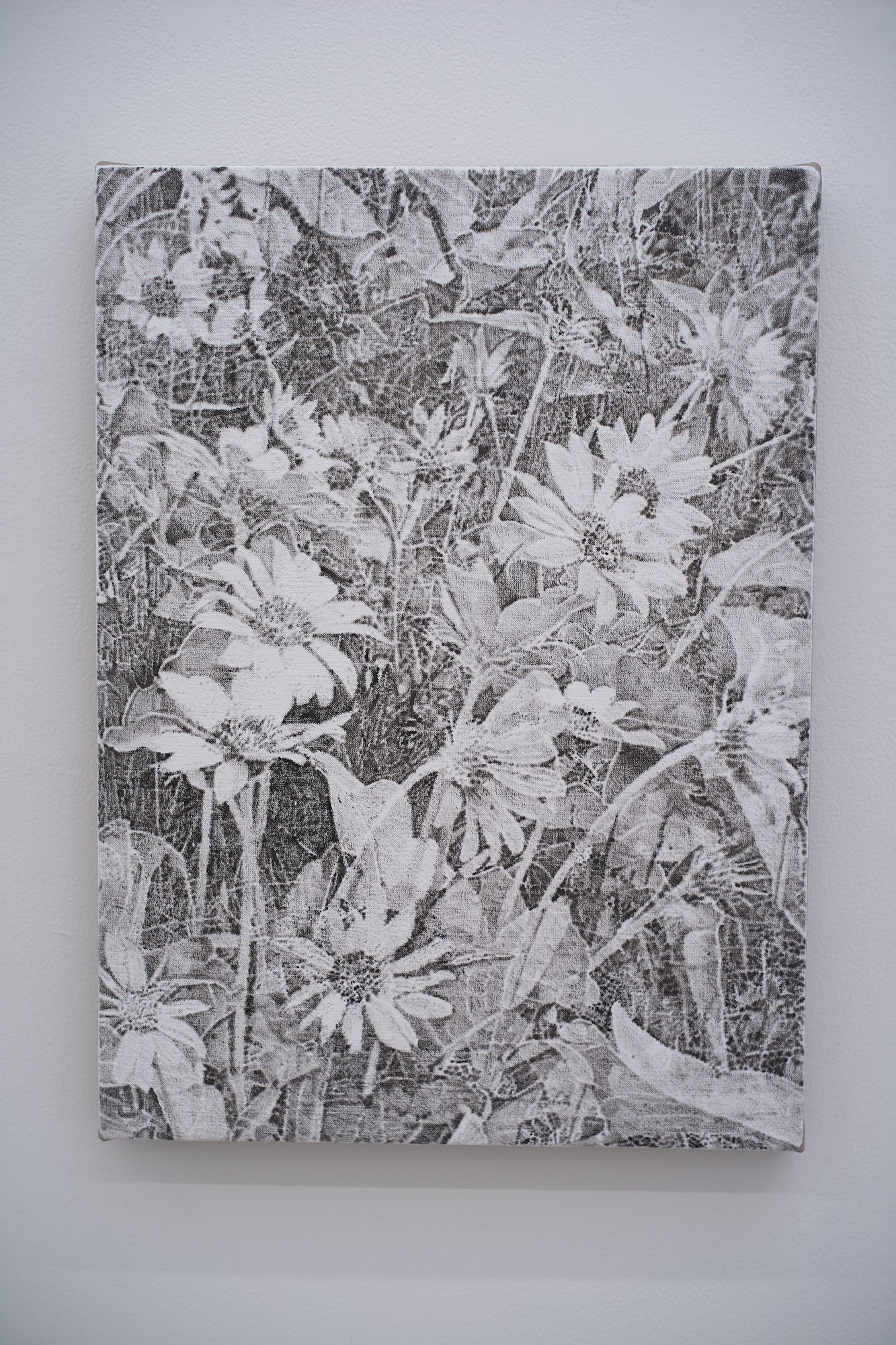

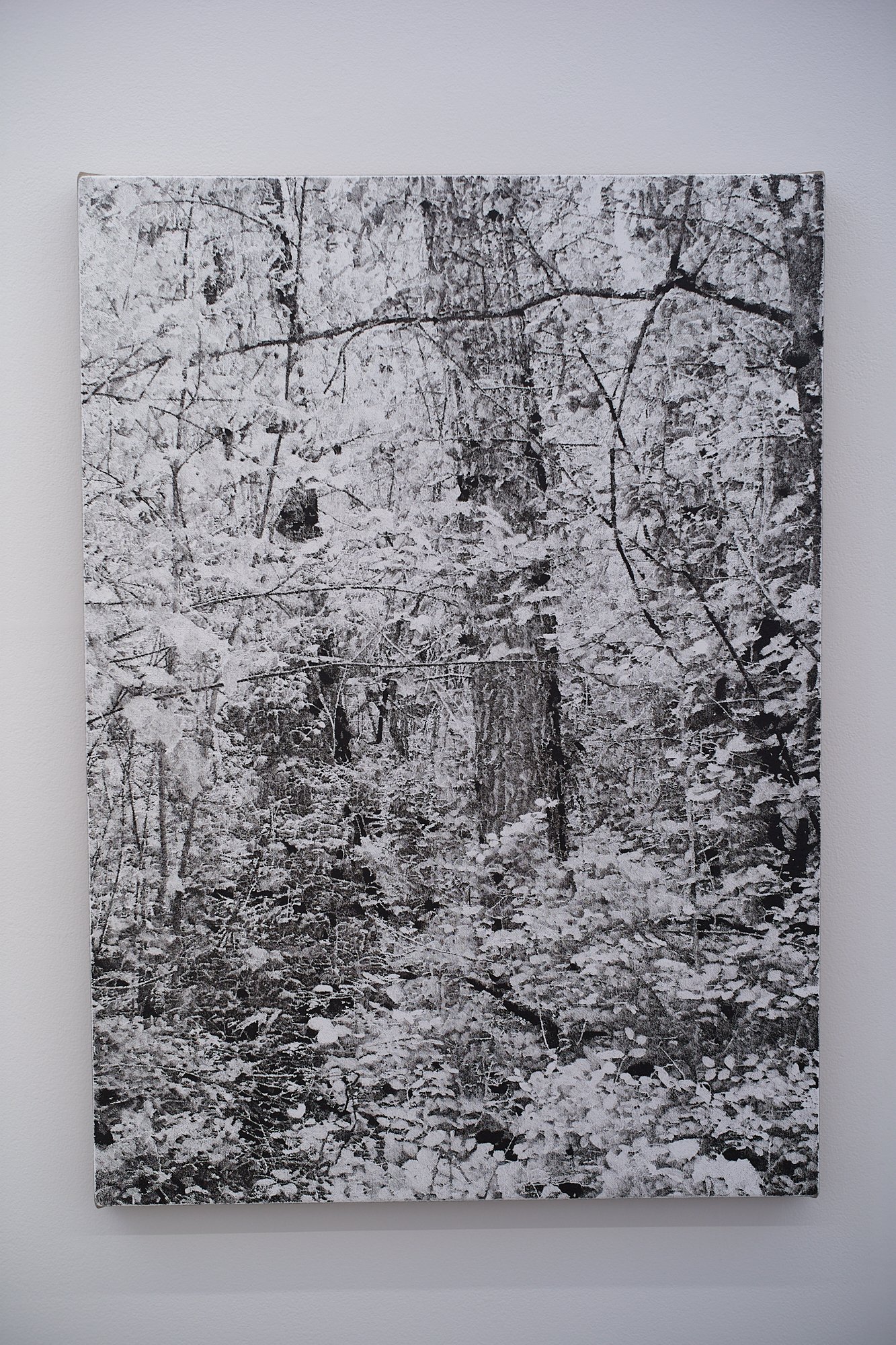

JAMES CHRONISTER

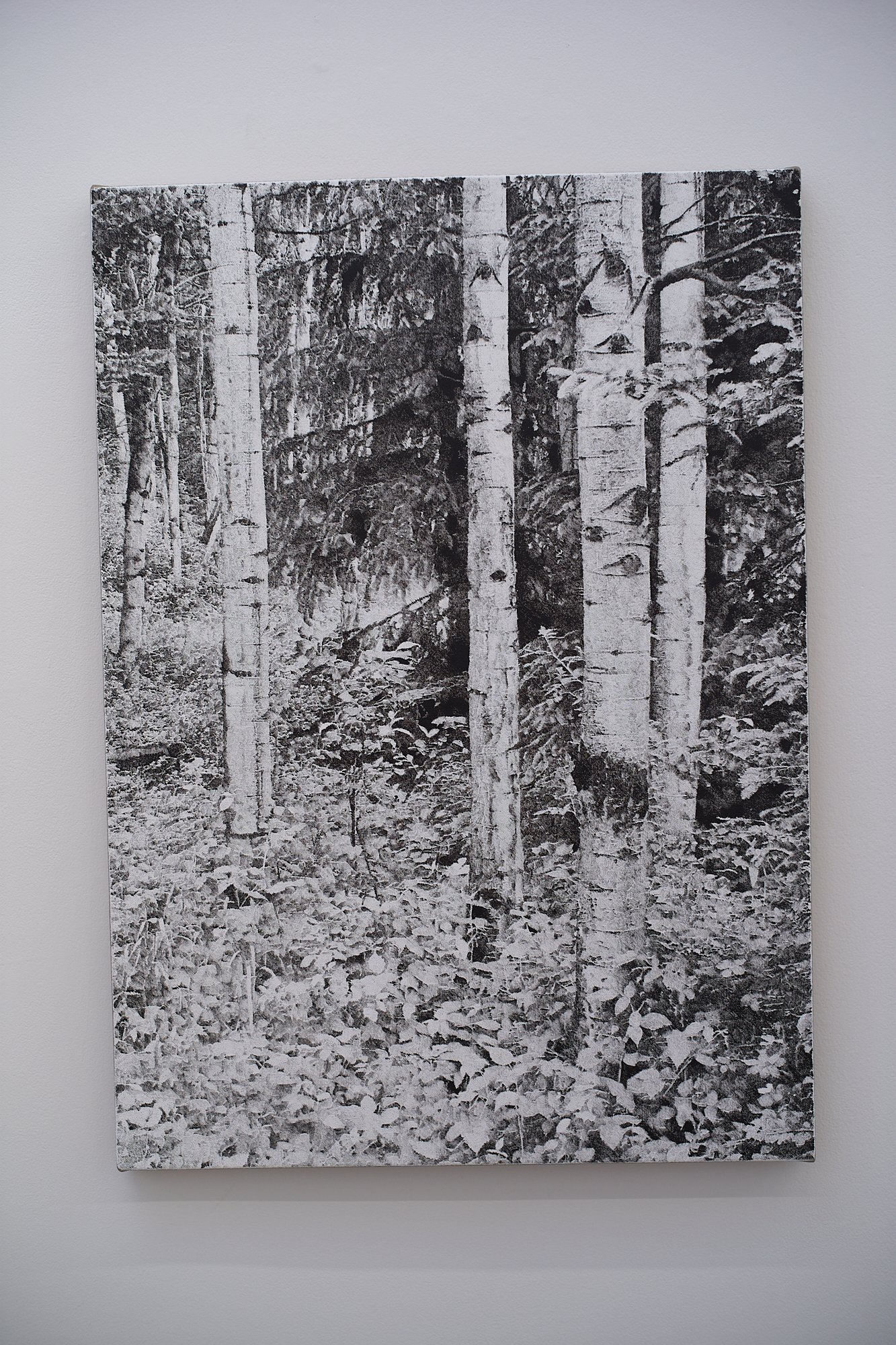

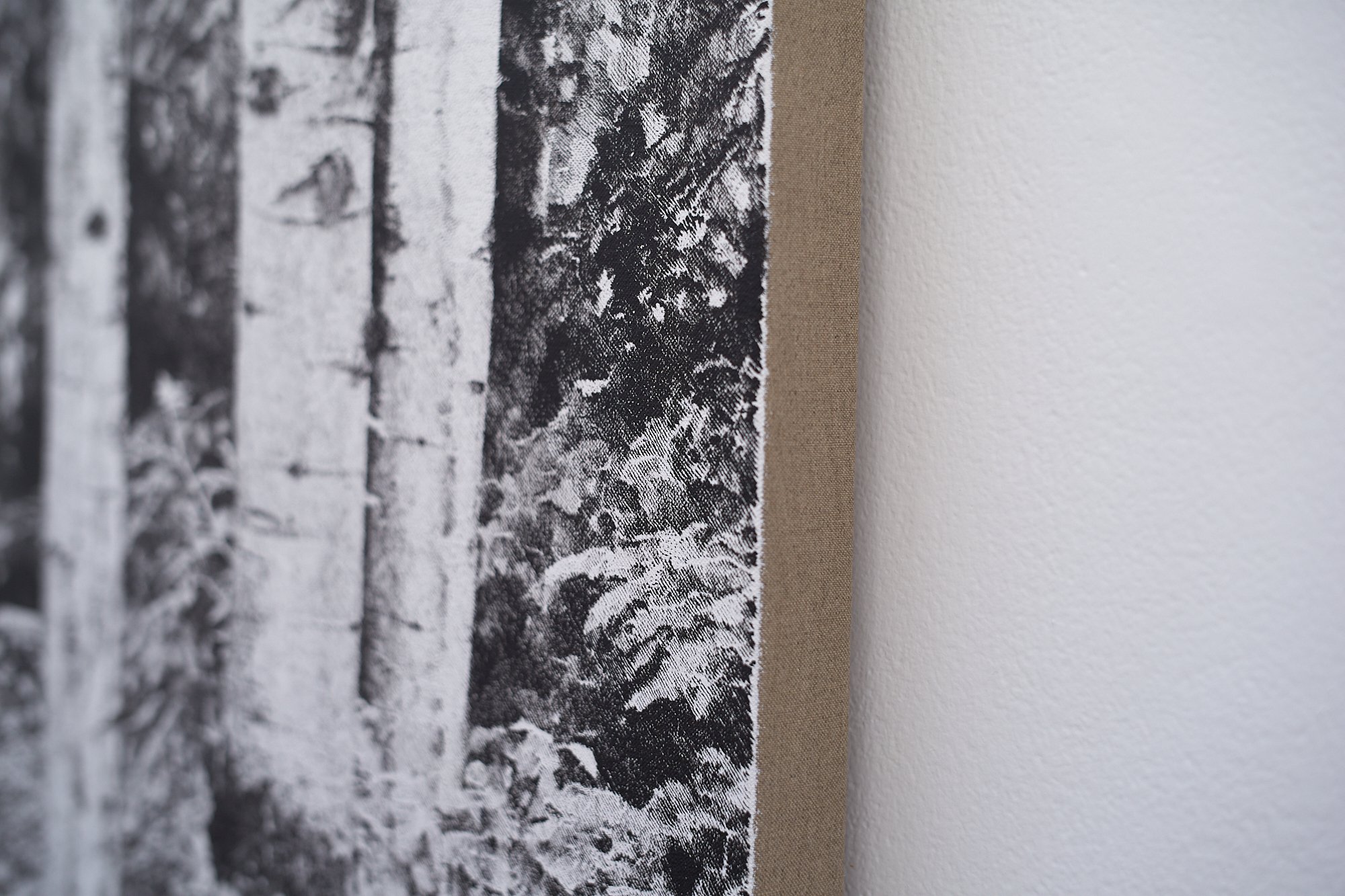

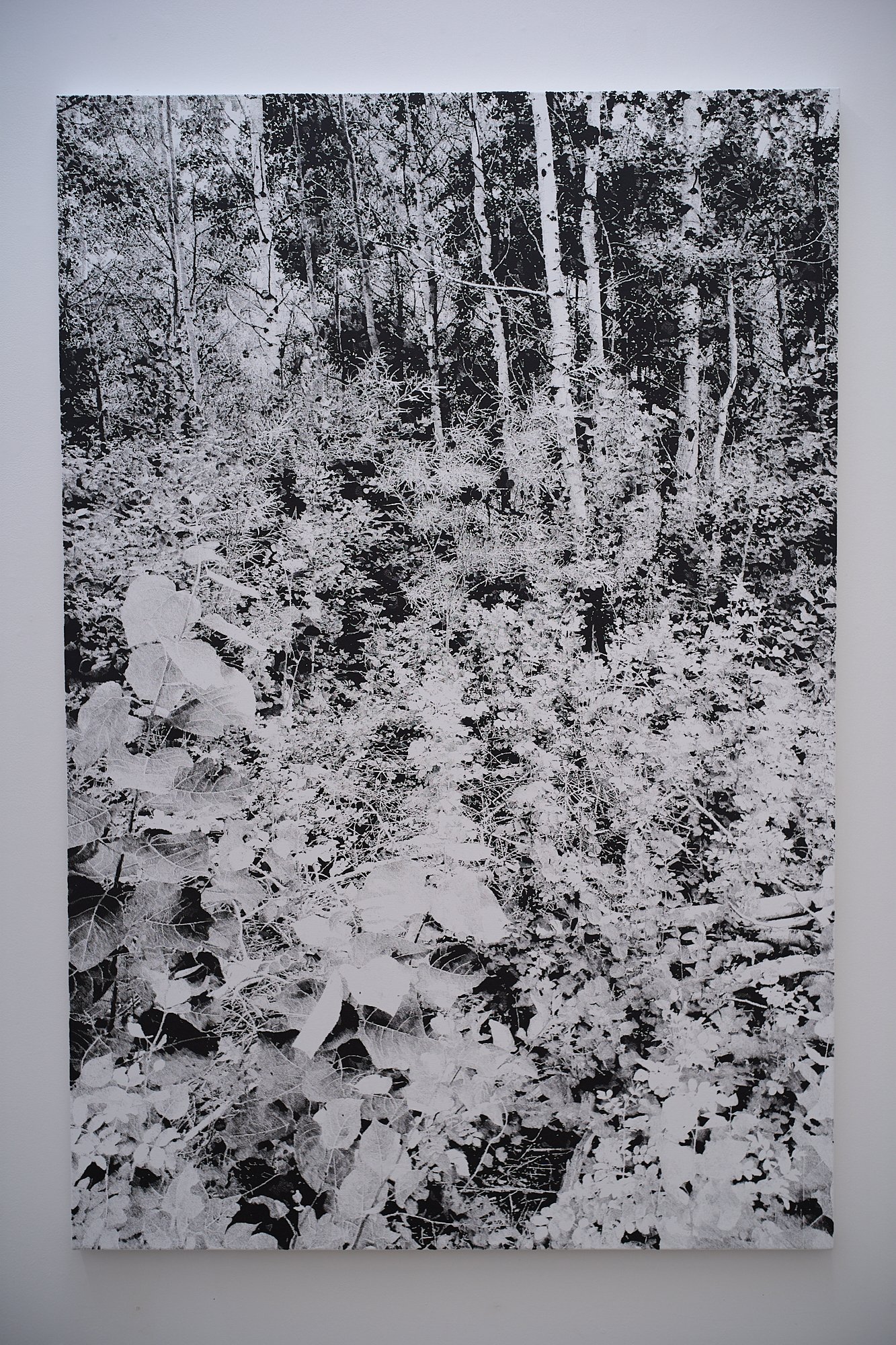

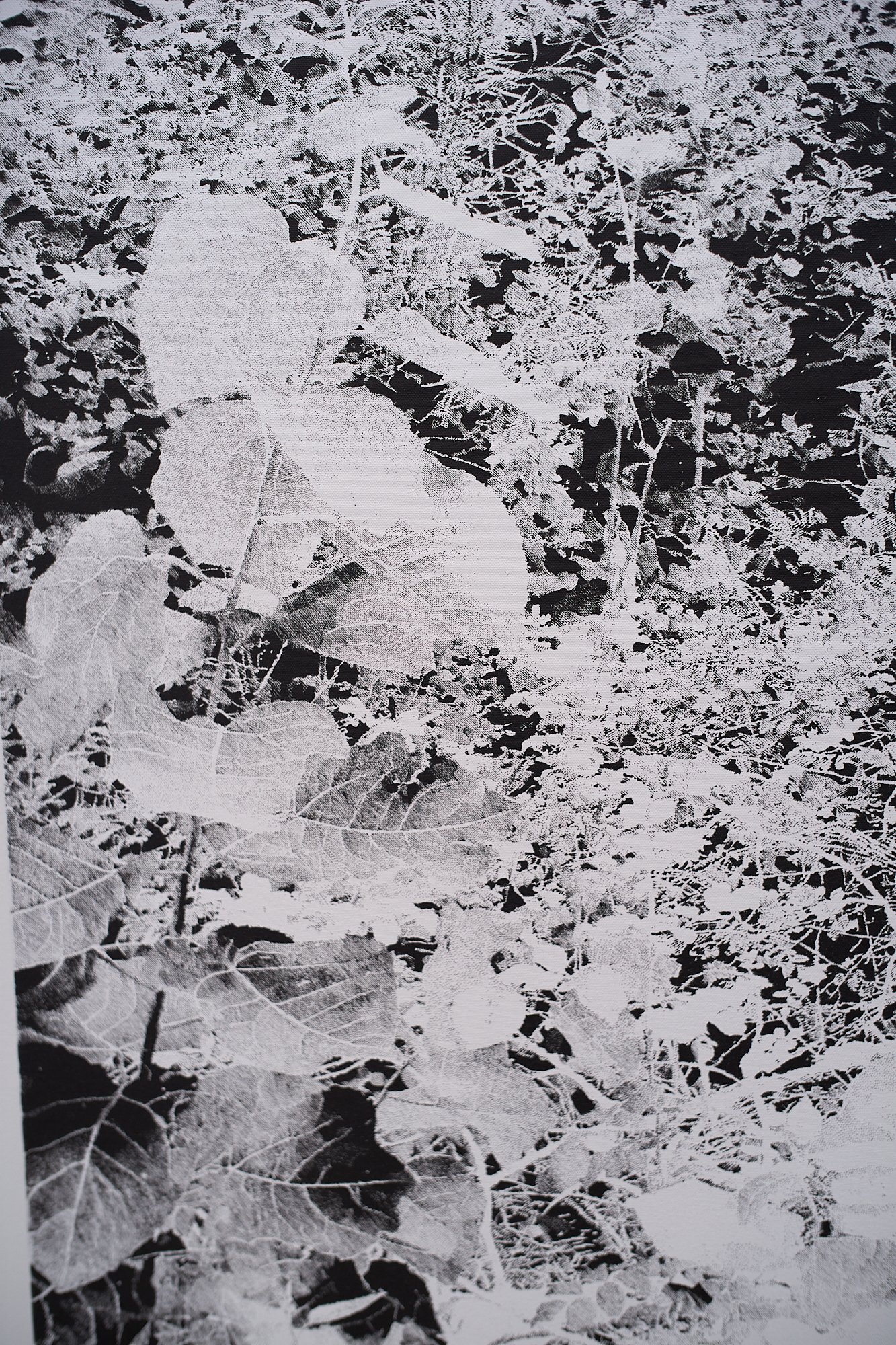

Niklas Asker: The Shroud

NICODIM

Los Angeles Upstairs

July 8 – August 12, 2023

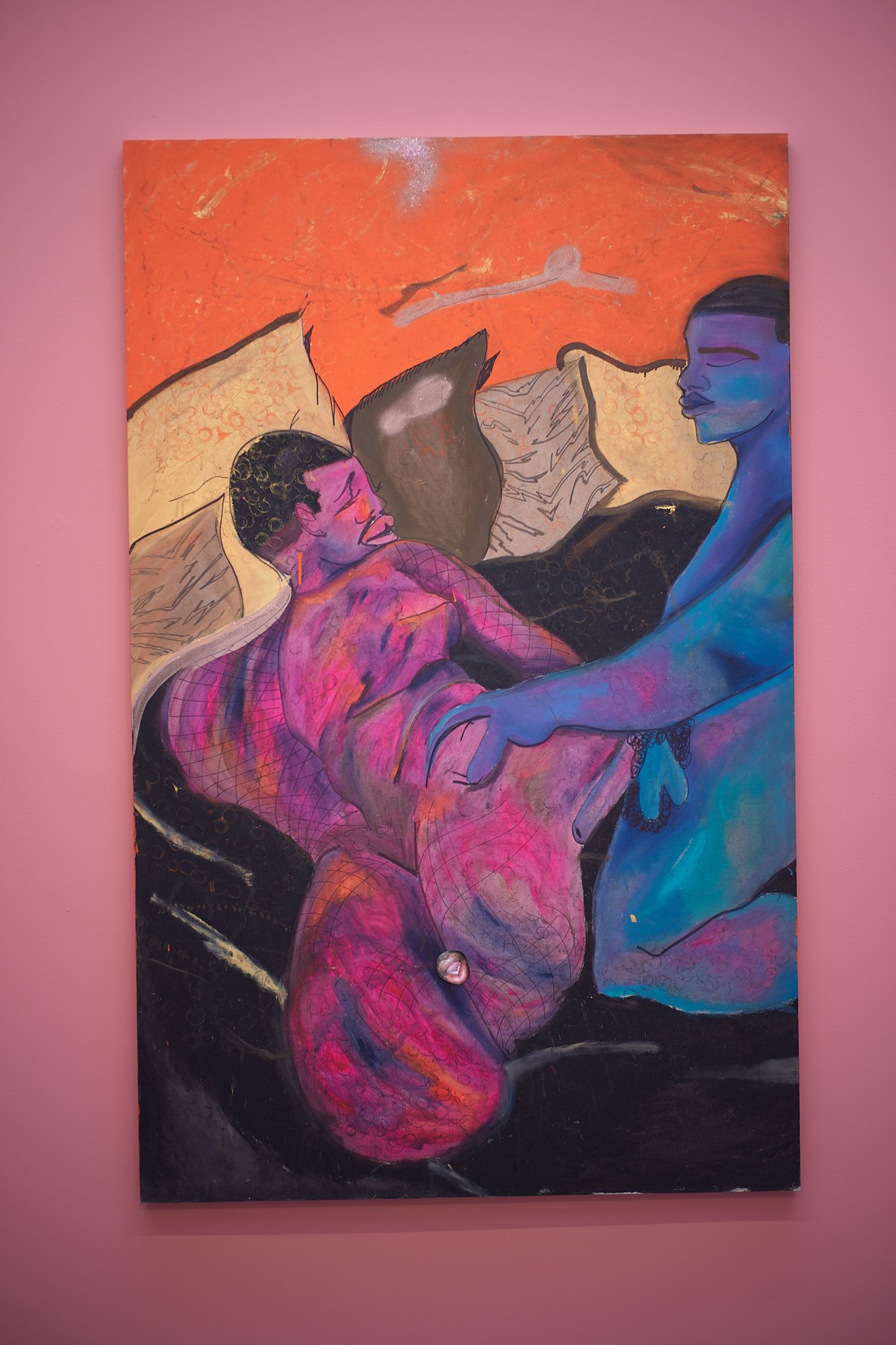

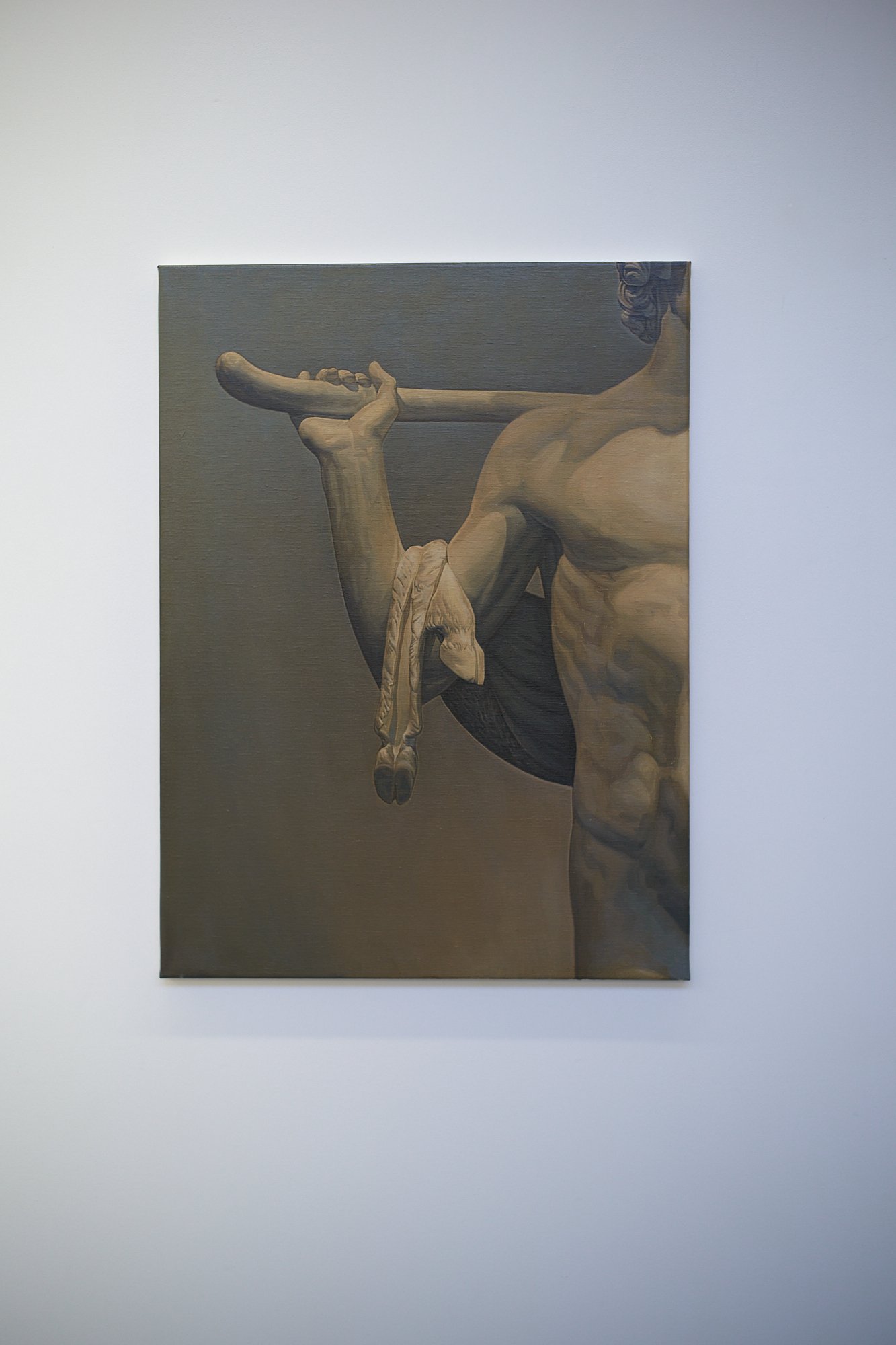

Will Thornton: Hypnagogic Sex Idols

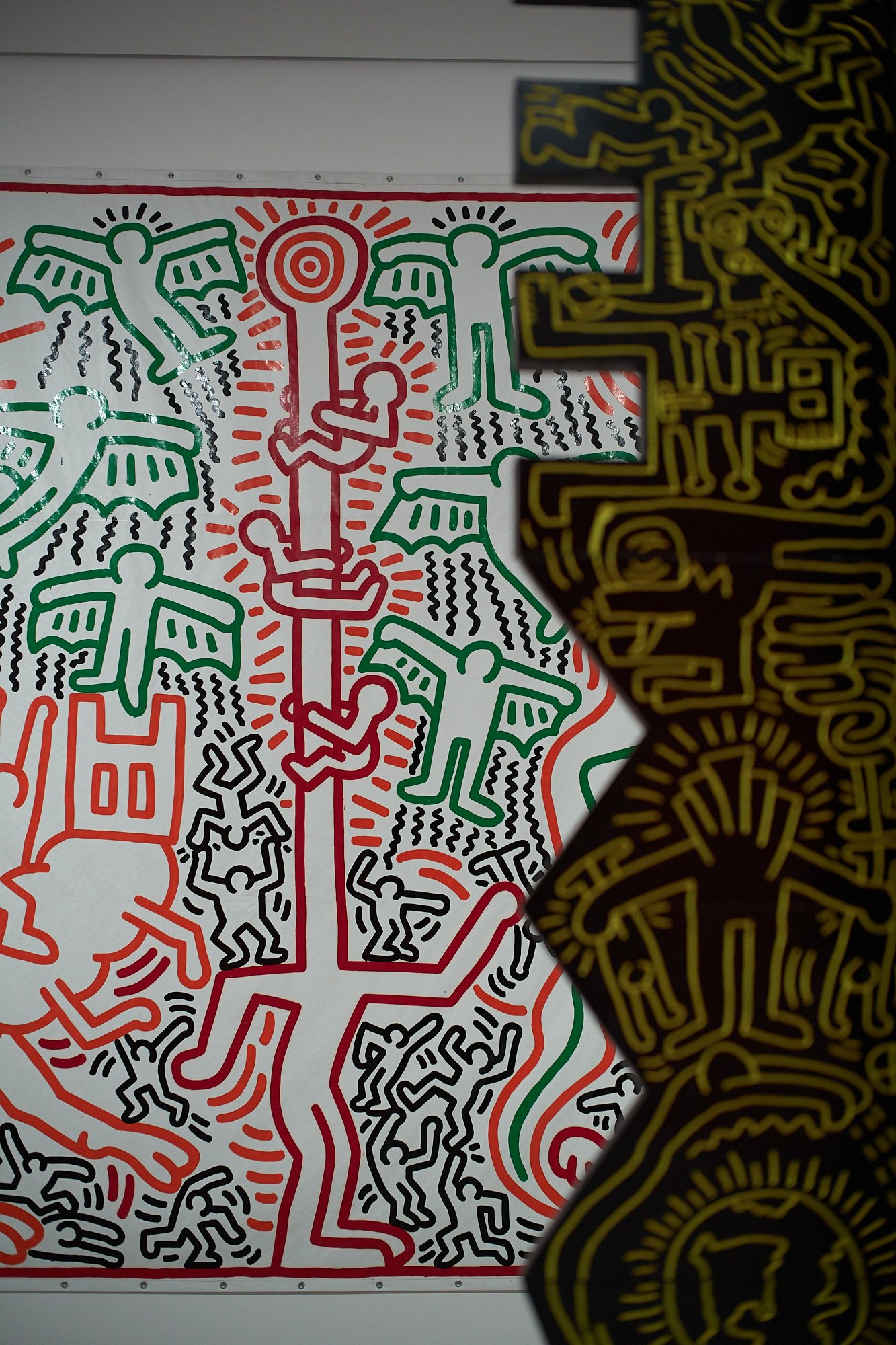

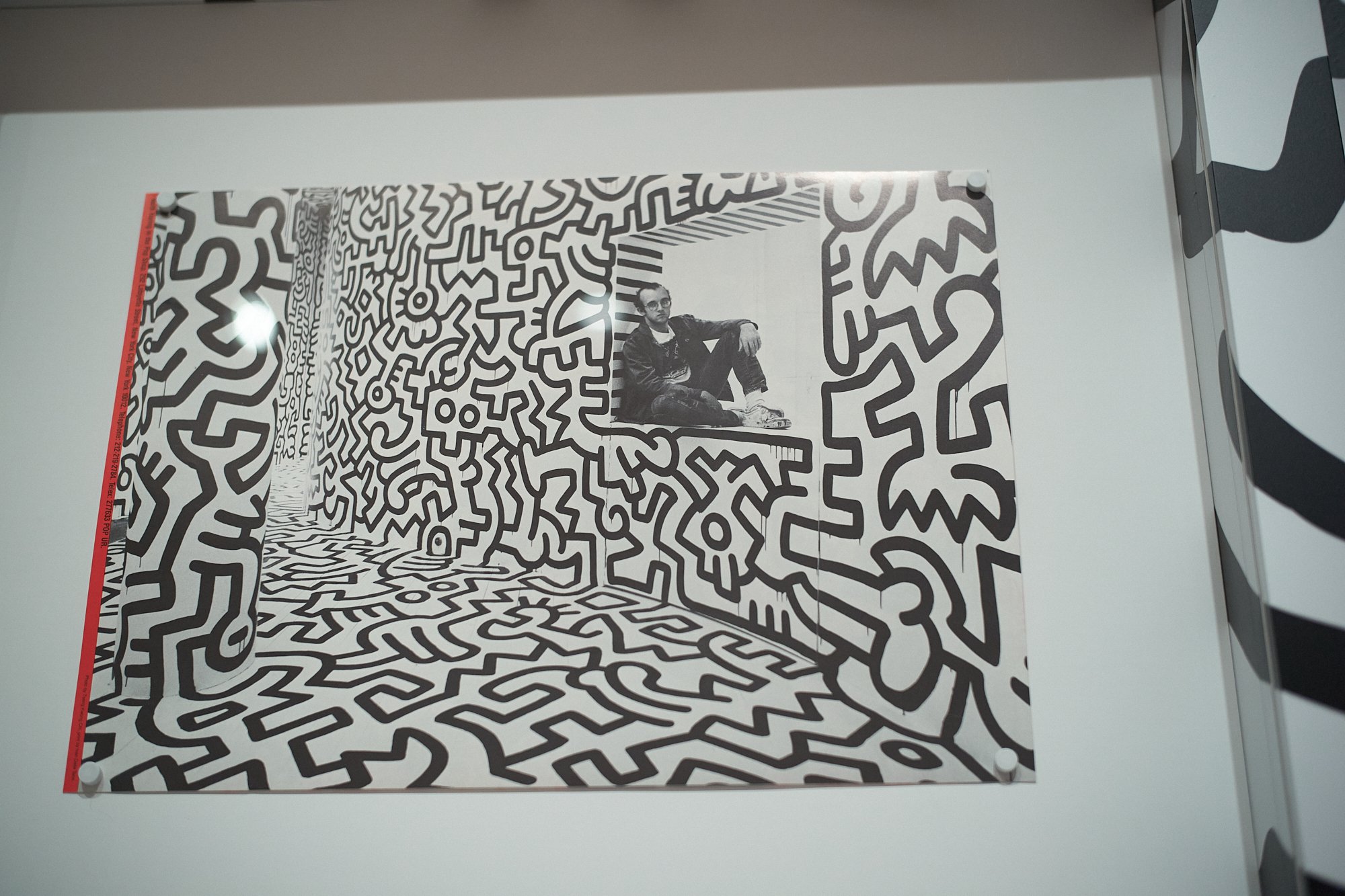

Keith Haring - Art is for Everybody

The Broad, Los Angeles

SPECIAL EXHIBITION

Keith Haring: Art Is for Everybody

May 27 - Oct 08, 2023