John McCracken

AKADEMIE X LESSONS IN ART + LIFE - lesson 26

TUTOR: Raqs Media Collective

Page 248

The Third Lesson: Time for Wine

The third lesson is about time. Sometimes, to learn this lesson, we have to prepare a feast - a feast with no food, but with a lot of wine and many notes. One of the forms this has taken is a symposium on time, which was first produced in the Wide Open School at the Hayward Gallery, London, in the summer of 2012. The form is simple and remains durable.

Fifteen or so participants sit in a large table, each with a plate and a wine glass in front of them. A set of carefully chosen notes on time printed on index cards appear on the plates, in the form of ‘courses’. Each ‘guest’ reads the ‘portion’ on his/her plate and everyone drinks, and after a round of readings (a course) the ‘table’ has a conversation. The idea is to let thinking, conversation and the requisite amount of wine do its job to add up to a stimulating consideration of time. Time itself is physically present. The cumulative, incremental effect of wine, factored through time, tranforms the experience into being enveloped inside a dilating fold. ‘Students’ cease to be students, and process elaborate theories. The reticent blossom into the loquacious, and the shy become bold. Once, at the end of the feast, people burst into song, and tears. Invariably, there has been laughter. The length of time this takes is a minimum of three hours, about the duration of a well-paced meal. As the courses gather momentum, an intensification of ideas and images, of associations and possibilities, takes hold, and we begin to get a grip on the qualia of time itself. We understand the relationship between, the presence of art. and the intensification of experience: of a different sense of time.

AKADEMIE X LESSONS IN ART + LIFE

AKADEMIE X LESSONS IN ART + LIFE

LESSON 23

TUTOR: Carrie Moyer

Page 220

Sharpen your visual intelligence by looking at art in person - Close looking is a means of gathering information in order to analyse a work of art within the parameters set by its maker. Through careful examination the object reveals its materials, size, scale; the processes and methods of its facture; the identity of the maker; its relationship to the history of the medium and genre as well as to the world at large. using this form of connoisseurship to decide if art is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ would defeat the purpose. It’s more like being a scientist and learning how to analyse and identify what you’re looking at.

Curation Fair - Tokyo

Introduction by Robert Motherwell, page 10, Dialogs with Marcel Duchamp, Pierre Cabanne

An artist must be unusually intelligent in order to grasp simultaneously many structured relations. In fact, intelligence can be considered as the capacity to grasp complex relations; in this sense, Leonardo’s intelligence, for instance, is almost beyond belief. Duchamp’s intelligence contributed many things, of course, but for me its greatest accomplishment was to take him beyond the merely “aesthetic” concerns that face every “modern” artist - whose role is neither religious nor communal, but instead secular and individual. This problem has been called “the despair of the aesthetic:” if all colors or nudes are equally pleasing to the eye, why does the artist choose one color or figure rather than another? If he does not make a purely “aesthetic” choice, he must look for further criteria on which to base his value judgments. Kierkegaard held that artistic criteria were first the real of the aesthetic, then the ethical, then the realm of the holy. Duchamp, as a nonbeliever, could not have accepted holiness as a criterion but, in setting up for himself complex technical problems or new ways of expressing erotic subject matter, for instance, he did find an ethic beyond the “aesthetic” for his ultimate choices. And his most successful works, paradoxically, take on that indirect beauty achieved only by those artists who have been concerned with more than the merely sensuous. In this way, Duchamp’s intelligence accomplished nearly everything possible within the reach of a modern artist, earning him the unlimited and fully justified respect of successive small groups of admirers throughout his life. But, as he often says in the following pages, it is posterity who will judge, and he, like Stendhal, had more faith in posterity than in his contemporaries. At the same time, one learns from his conversations of an extraordinary artistic adventure, filled with direction, discipline, and disdain for art as a trade and for the repetition of what has already been done.

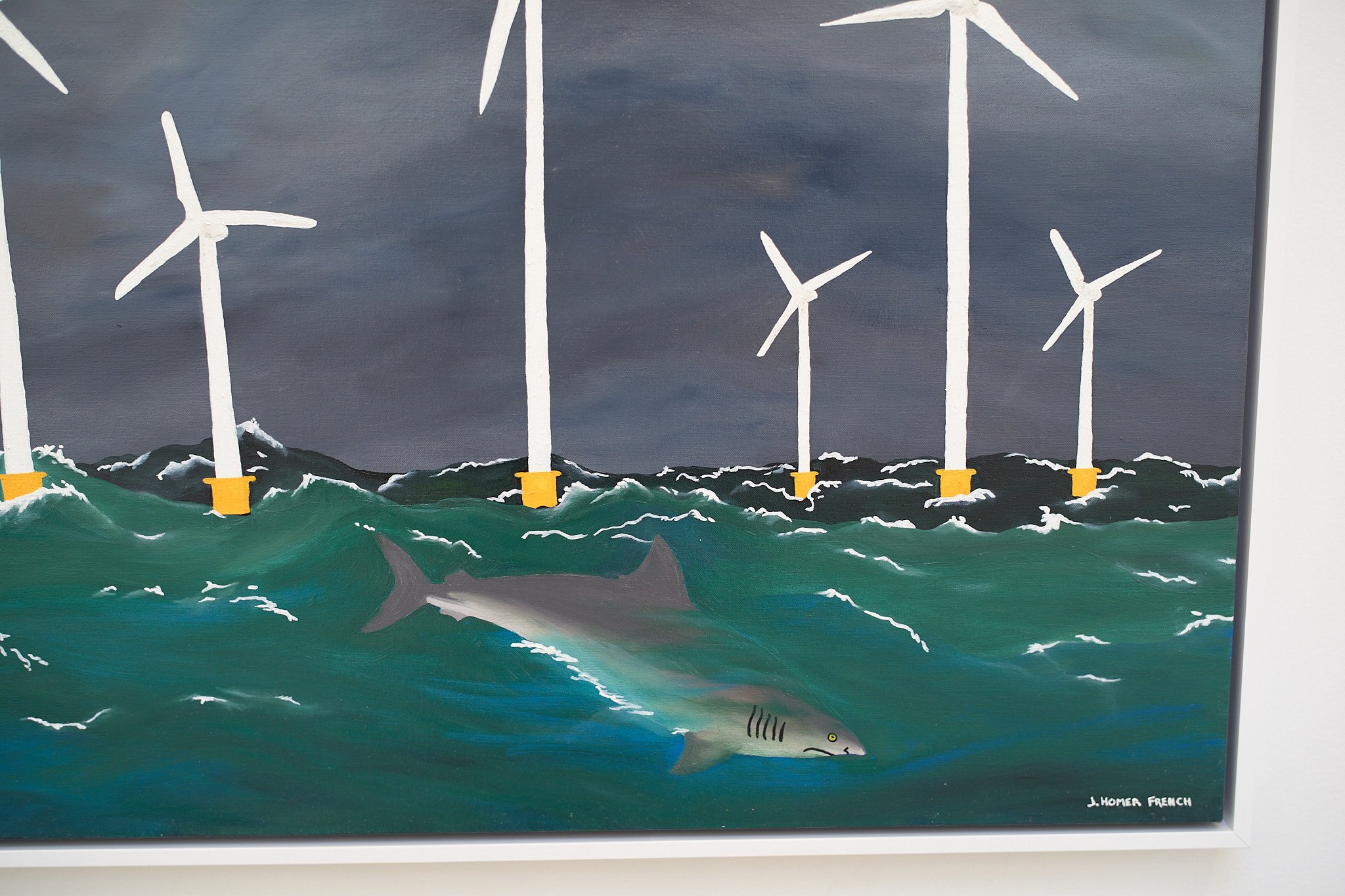

Jessie Homer French - Normal Landscapes

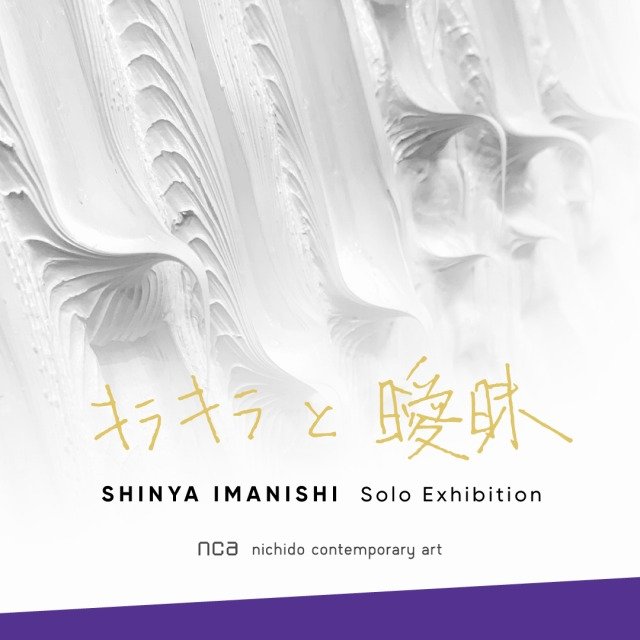

Shinya Imanishi: Twinkles / Out of focus

Daniel Brush - Thinking about Monet

21_21 DESIGN SIGHT Gallery 3

9-7-6 Akasaka, Minato-ku

107-0052 Tokyo

Exhibition Period:

2024 Jan 19 (Fri) - Apr 15 (Mon)

*Closed on: Jan 30 (Tue), Feb 13 (Tue), March 11 (Mon)

DAVID KORTY Greensleeves

BEN TONG The Violet Hour

Marina Perez Simão Solanaceae

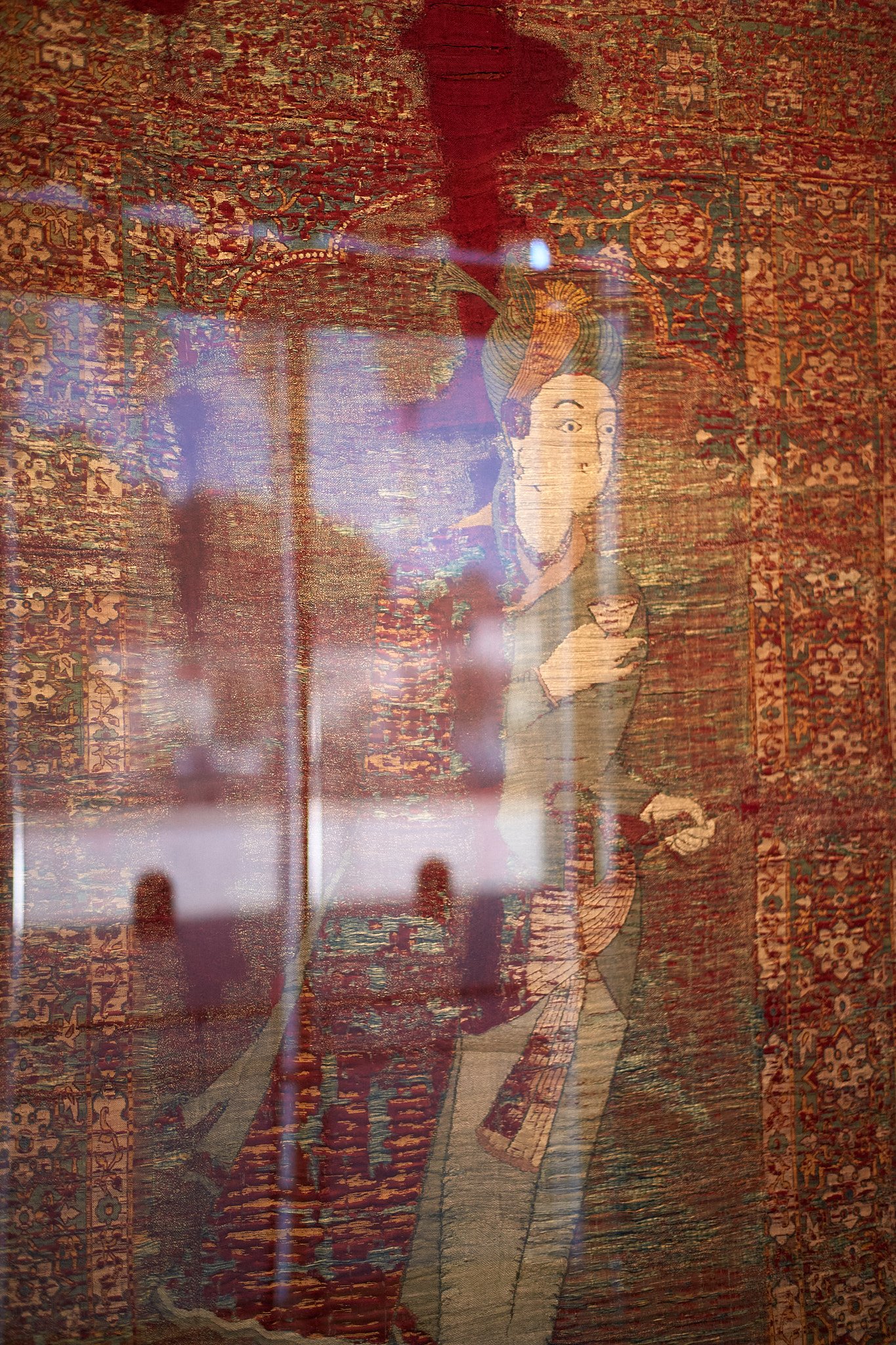

The World Made Wondrous: The Dutch Collector’s Cabinet and the Politics of Possession

Thirty Years: Written with a Splash of Blood

AKADEMIE X LESSONS IN ART + LIFE - TUTOR: THOMAS LAWSON

AKADEMIE X LESSONS IN ART + LIFE

LESSON 19

TUTOR: Thomas Lawson

Page 178

Artists notice stuff - the way things come together or fall apart, the telling detail or overlooked ruin, the tell-tale gesture. To be an artist, you have to train yourself to pay attention to the world in which you live, constantly looking for clues, always aware of your surroundings. Make notes, try observational drawing or taking photographs, study how things are made. There is no one method here. The task is to find a way to notice the details that make sense to you, the details that will open your eyes to content.

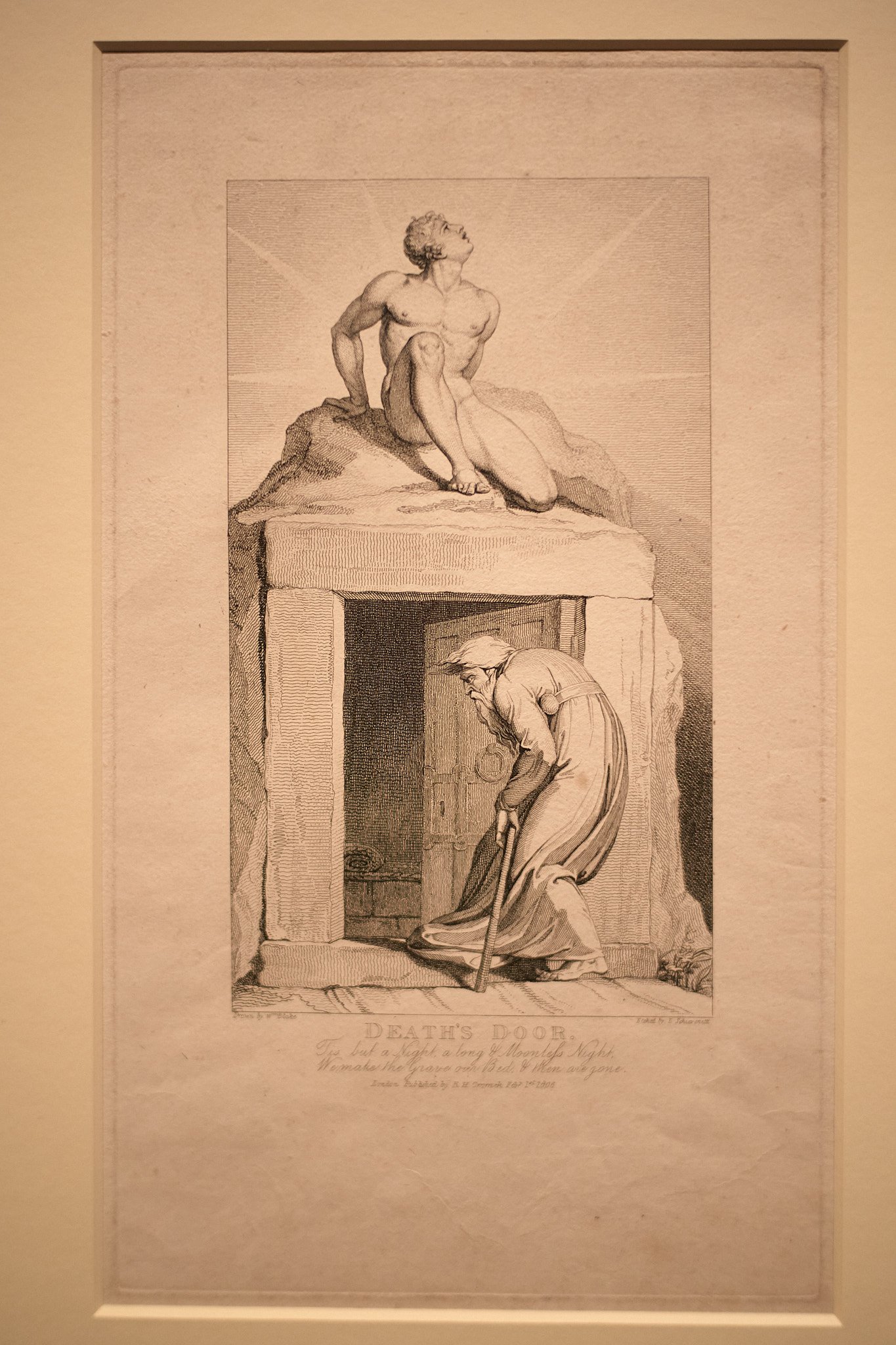

William Blake

Wagner - Das Rheingold

Composed: 1854

Length: c. 150 minutes

Orchestration: piccolo, 3 flutes, 3 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 8 horns (5th and 6th=tenor Wagner tubas, 7th and 8th=bass Wagner tubas), 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, bass trombone, contrabass trombone, tuba, 2 timpani, percussion (anvils, cymbals, hammer, tam-tam, triangle), 7 harps, strings, and vocal soloists

https://www.laphil.com/musicdb/pieces/6767/das-rheingold