I had Bellini’s final opera, I Puritani, on 1.6, 1.10, 1.18 at the Metropolitan Opera. From the very opening, the orchestra scattered sparks and moved into the hunting-horn tutti. The theme was taken up and echoed throughout the orchestra as the male chorus announced the coming of dawn. The string tremors spread outward from both sides, not like gentle morning light, but like the sun scorching the ground. The horn theme drew closer, joined by the bassoon and the timpani's rolling. Snare drums entered from left and right, and the Puritans’ triple-meter march began. Male chorus and orchestra intertwined like a massive concerto. In these first ten minutes, the sheer clarity was overwhelming—I couldn't open my eyes.

A chorale followed, and after the singers’ prayer in the banda concluded, a festive celebration began for the wedding of Elvira and Arturo. The pure choral sound blended seamlessly with exchanges among the woodwinds, including flute and piccolo. Then appeared the Puritan knight Riccardo, singing of his lingering love for Elvira. Artur Ruciński’s voice seemed to defy breath itself; the more he sang, the more time appeared to stretch. He dragged the ends of phrases darkly and heavily, moving into the next phrase without taking a breath. It felt like a single, unbroken signature drawn across the vast space of the Met. This was not written in the score—it was his own expression—and the orchestra, too, seemed to look up toward him.

The orchestra continued to support the voice through rhythmic articulation, harmony, and even shared melody. Upon the repetition of simple rhythmic patterns, the human voice freely traced inner states of mind, memory, and experience. In 1835, when harmony and counterpoint were already fully developed, Bellini created music that resembles a concerto for voice and orchestra. To depict the inner life freely through the human voice—Ruciński’s singing offered a vivid demonstration of the world of bel canto.

Lisette Oropesa’s Elvira in the first act was gentle and innocent; her clear, slightly moist voice, like a whispered secret, transformed purity directly into sound. In the second act, the tempo slowed drastically, and time itself seemed to come to a halt. The middle voices, especially the violas, took on the weight of her anguish, allowing Oropesa’s melodic line to rise effortlessly above them. As the aria was repeated, the emotional depth intensified, and the outline of the final phrase was etched into space like an afterimage. Her voice remained transparent and soft; the storm of emotion was still contained within, revealed gradually through subtle dynamics and vibrato, letting the listener glimpse the trembling of her heart.

The chorus was consistently innocent and transparent. Since Tilman Michael assumed leadership, the chorus has functioned less as a collection of individual voices and more as a single, unified sound. The shaping of vowels, the expansion of overtones, and the clarity of dramatic movement felt newly vivid. The chorus no longer served as mere background; it governed the psychological atmosphere of the drama, powerfully intensifying Elvira’s confusion and anxiety at the end of Act I. That is why the solo voice that follows emerges with such striking clarity.

In Act III, Lawrence Brownlee’s Arturo brought unwavering balance and reassurance to every phrase he sang. In the reunion duet, the voices grasped the listener’s heart directly, love piling upon love without a moment to breathe. In the end, the Puritans’ triple-meter march resounded once more, proclaiming order and victory, while leaving behind a lingering resonance of what had been endured.

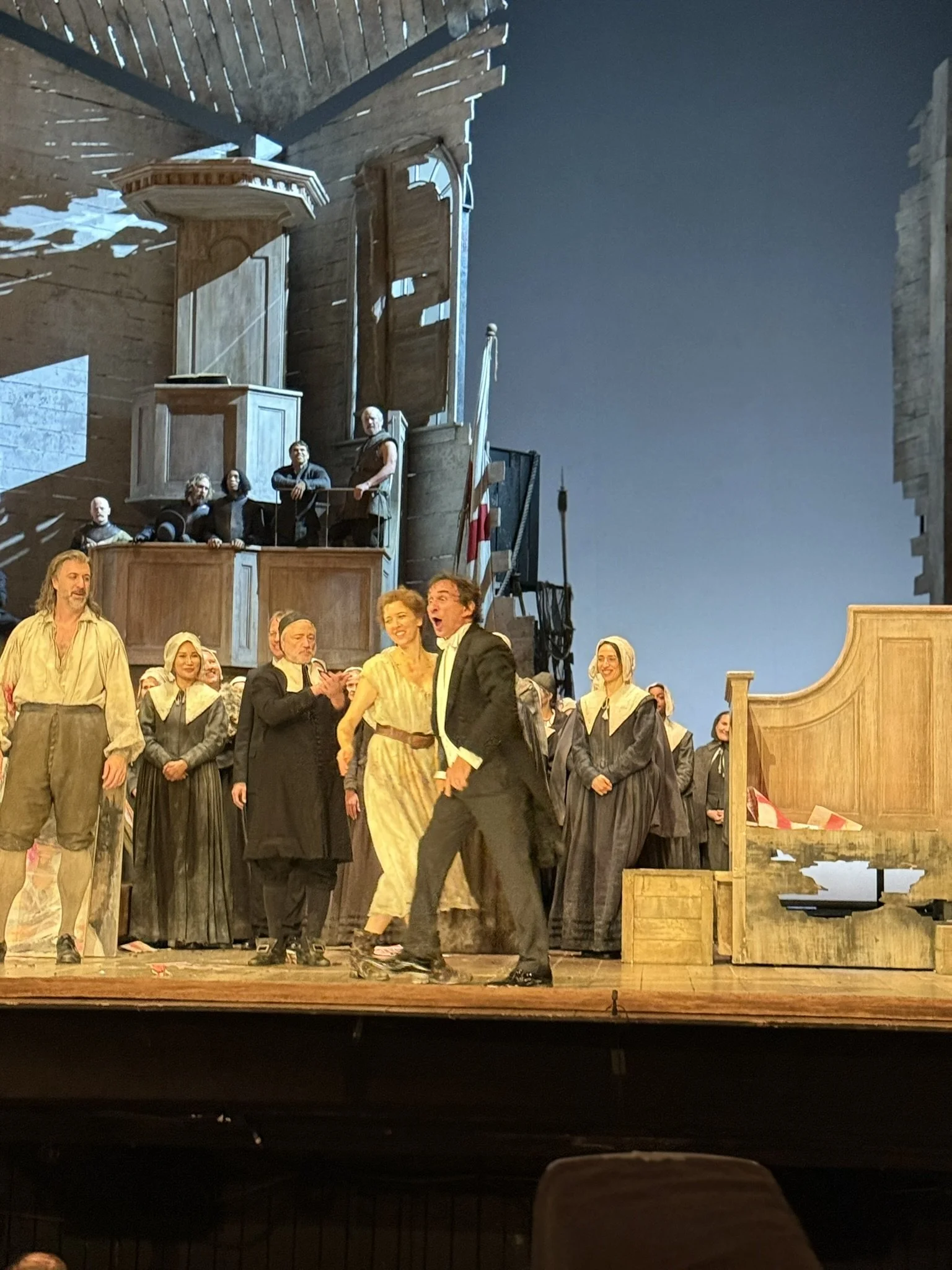

This opera combines simple marches into a structure of remarkable complexity, like a kaleidoscope of sound. Against the singers’ melodic lines, the staging, sets, and lighting each assert themselves strongly, resulting in a degree of visual confusion at present. Yet new productions mature over time—not only on stage, but also in the audience's perception and understanding. I Puritani portrays the purity of the human heart and, at the same time, feels like a mirror reflecting both our present and our future.

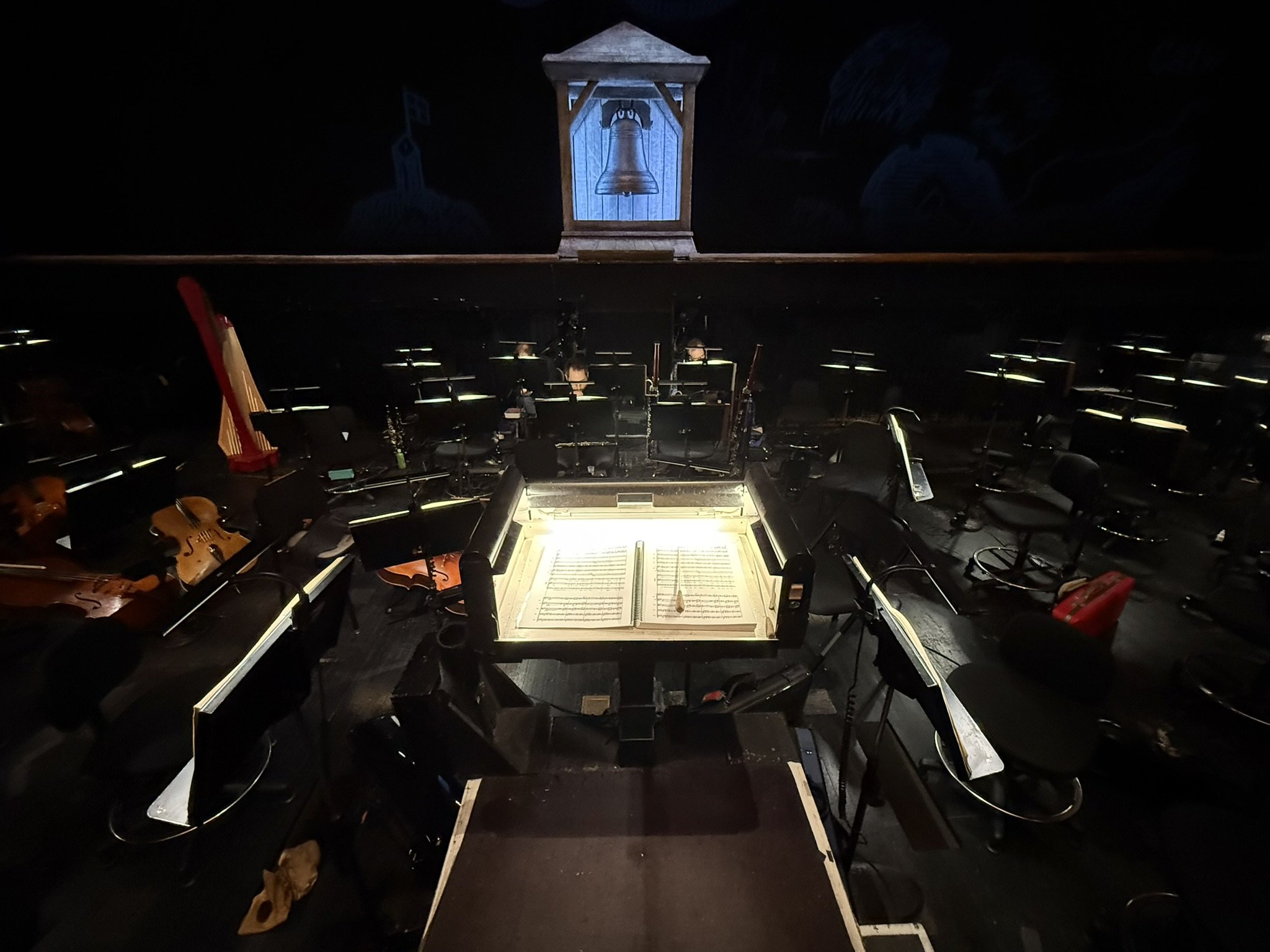

1.18.2026 日曜の午後の最後の清教徒の幕が下りる直前。コンサートマスターのベンジャミンと、ビオラのミラン。そして、奥にはクラリネットのシルビオとバスーンのビリーが見える。指揮台にはマルコ・アルミリアートの指揮棒が2本とマエストロのスコアが閉じておいてある。

ポディウムから正面にベル。ベルカントの象徴のようだ。幕中はこのベルがずっと高く中央に配置されている。

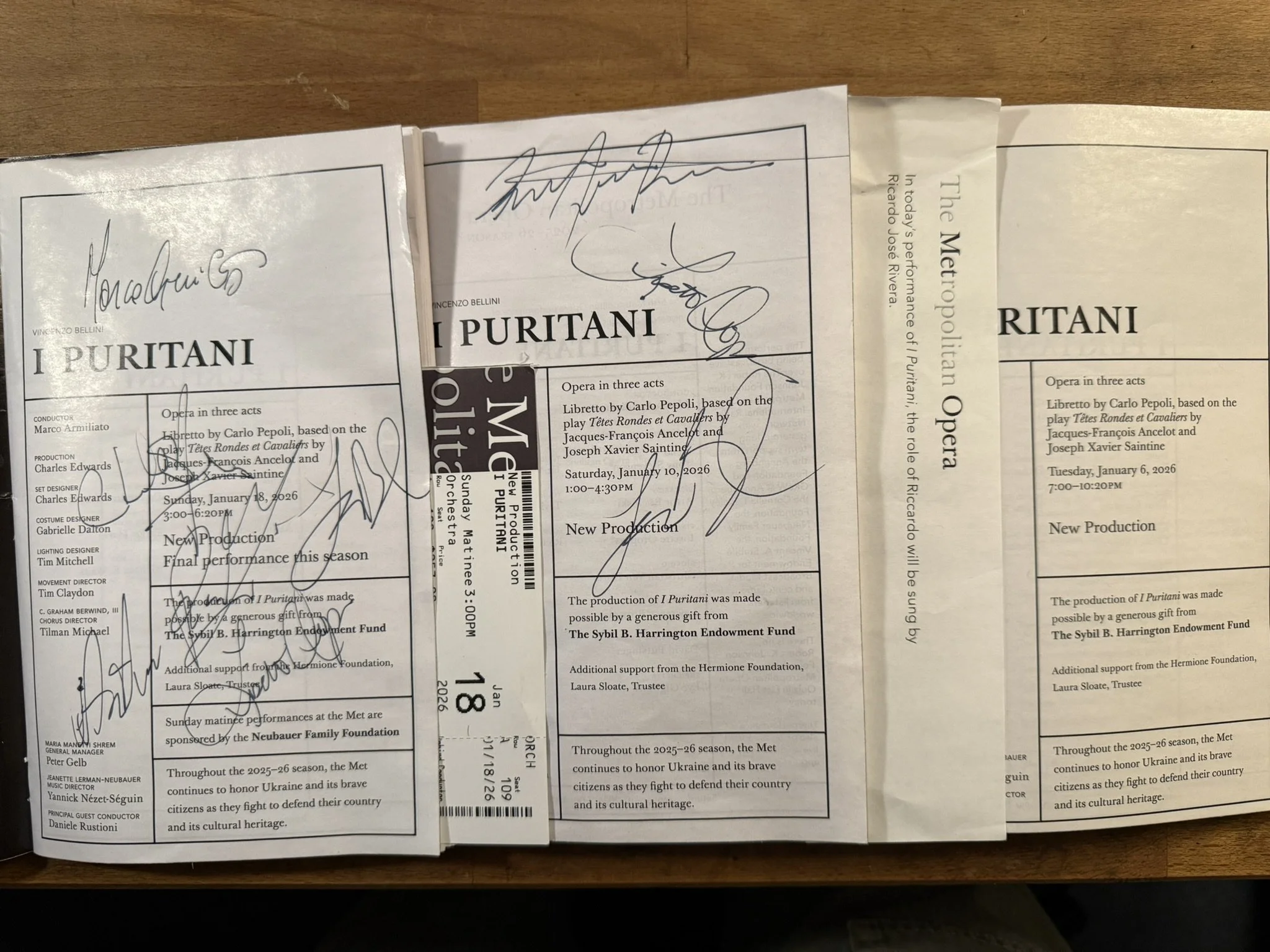

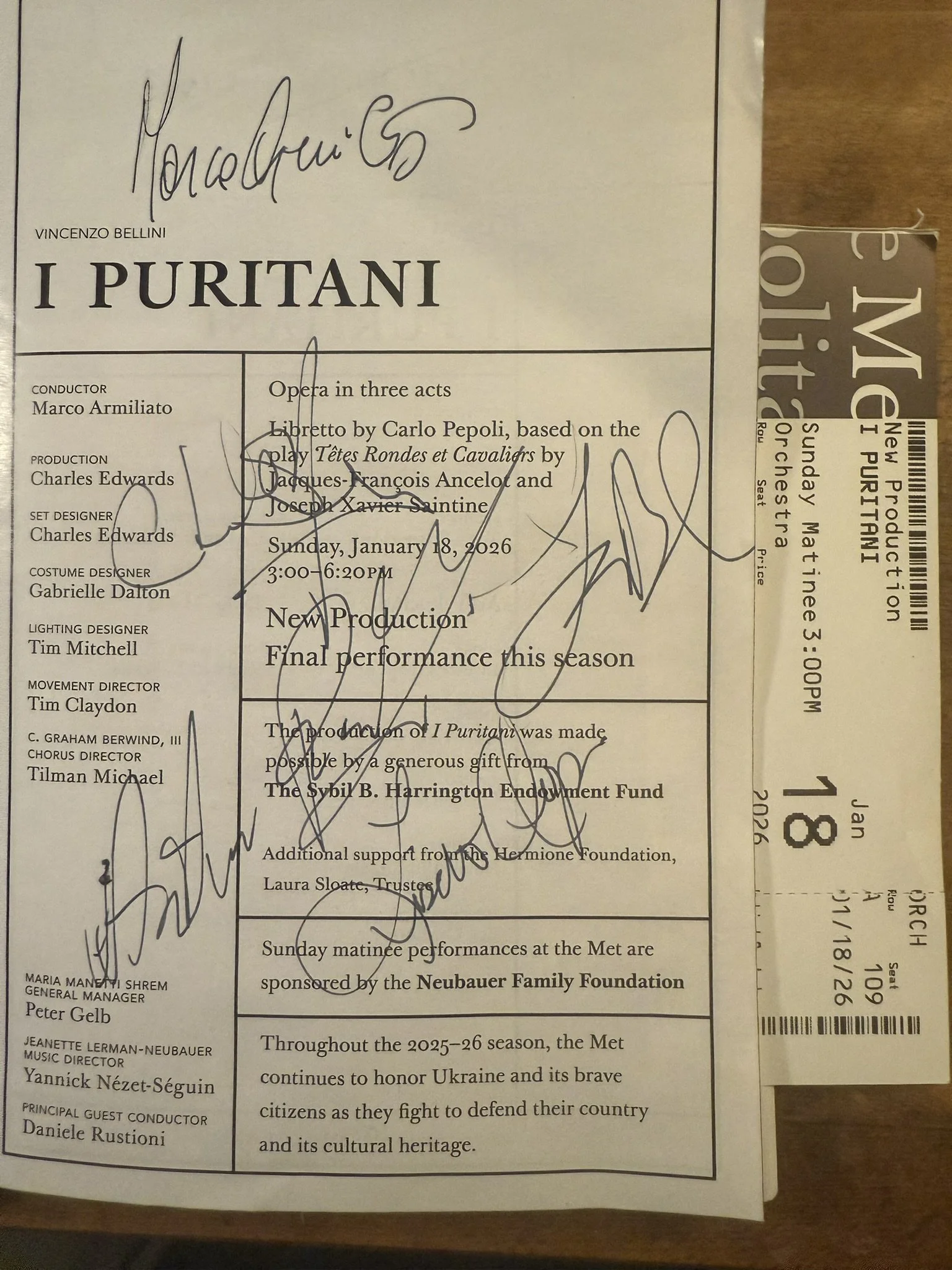

最後の公演のプログラムに全員のサイン。

リセッテ・オロペサ。ベルカントソプラノ。トリフォノフのレンディションの様な精密な歌唱。人の声が楽器のようなビルトゥオージティを魅せる。

チェロ首席夫妻とピッコロのジェニファーとフルートのチェルシー。

マルコ・アルミリアート。前日はバタフライをふった。

合唱がうまかった。

ベッリーニ最後のオペラ、清教徒を、2026年1月6日(火)夜、1月10日(土)午後、1月18日(日)午後の三度、メトロポリタン歌劇場で聴いた。

冒頭、オーケストラが火花を散らすように鳴り響き、やがてハンティング・ホルンのトゥッティへと続く。その主題は管弦に受け渡され、男声合唱が夜明けを告げる。

弦のトレモロは、柔らかな朝の光というより、地面をじりじりと焼く太陽の熱のように、左右から広がっていく。ホルンの主題は次第に迫り、バスーンとティンパニのトレモロがそれを支える。左右からスネアが鳴り、三拍子の清教徒のマーチが始まる。そこへ男声合唱とオーケストラが、まるで巨大なコンチェルトのように絡み合う。ここまで約10分、音の鮮明さに圧倒されて目が開かなかった。

コラールが続き、バンダで歌手たちの祈りが終わると、エルヴィーラとアルトゥーロの結婚を祝う祝祭が始まる。清らかな合唱がフルートやピッコロを含む木管の掛け合いと溶け合って響く。そこに現れる清教徒の騎士リッカルドは、愛するエルヴィーラへの未練を歌う。Artur Rucińskiの声は異様なほどブレスが長く、歌えば歌うほど時間が引き伸ばされるように感じられる。フレーズの終わりを暗く重く引きずり、そのまま息継ぎな しで次のフレーズへ進む歌い方は、メットの空間に一筆書きで描かれたサインのようだった。楽譜には書かれていない、彼自身の表現であり、オーケストラもまた彼を見上げていた。

オーケストラは、リズムのアーティキュレーション、ハーモニー、そして時にはメロディーを共有することで、歌声を支え続けた。シンプルなリズムパターンが繰り返される中で、人間の声は内面の状態、記憶、そして経験を自由に描き出した。1835年、ハーモニーと対位法がすでに十分に発展していた時代に、ベッリーニは声とオーケストラのための協奏曲のような音楽を創造した。人間の声を通して内面世界を自由に表現するルチンスキーの歌唱は、ベルカントを鮮やかに示していた。

エルヴィーラを歌うLisette Oropesaは、第1幕では穏やかで無邪気な歌唱を聴かせ、内緒話をするような湿り気を帯びた声が、純粋さをそのまま音にする。第2幕に入ると、テンポは極端に遅くなり、時間が止まる。中声部、とりわけビオラが胸を締め付ける、そこにオロペサの旋律を見事に浮かび上がらせる。繰り返されるアリアは、感情が深まり、歌い終わりの輪郭を空間に残像のように刻む。声は透明で柔らかく、感情の嵐はまだ内に秘められ、微細なダイナミクスとビブラートによって、心の揺れが少しずつ透けて見えるようだった。

合唱は終始、清らかで透明感に満ちていた。ティルマン・ミヒャエルの合唱は個々の声の集まりというより、一つの統一された響きとして、母音の響き、倍音の広がり、そして劇の明瞭さを鮮やかに示す。合唱はもはや単なる背景ではなく、ドラマの心理を支配し、1幕の終盤のエルヴィラの混乱と不安を増幅させた。そして、続くソロの声が明瞭に響く。

3幕でアルトゥーロを歌うLawrence Brownleeは、どんなフレーズでも揺るがない重心と安心の歌唱。再会の二重唱は、声が聴き手の心をつかみ、息つく暇もなく愛が重ねられていく。最後、清教徒の三拍子のマーチが鳴り、秩序と勝利が残り響く。

このオペラはシンプルなマルチャを組み合わせた、複雑な構造で、音の万華鏡のようだった。歌手たちが描くメロディの空間アートに、演技やセット、照明は主張を持ち、今はまだ混乱もあるが、新しいプロダクションは聴衆の感覚や理解と一緒に成熟していく。清教徒は、人の純粋な心を描く、私たちの現在と未来を映し出す鏡だと感じた。