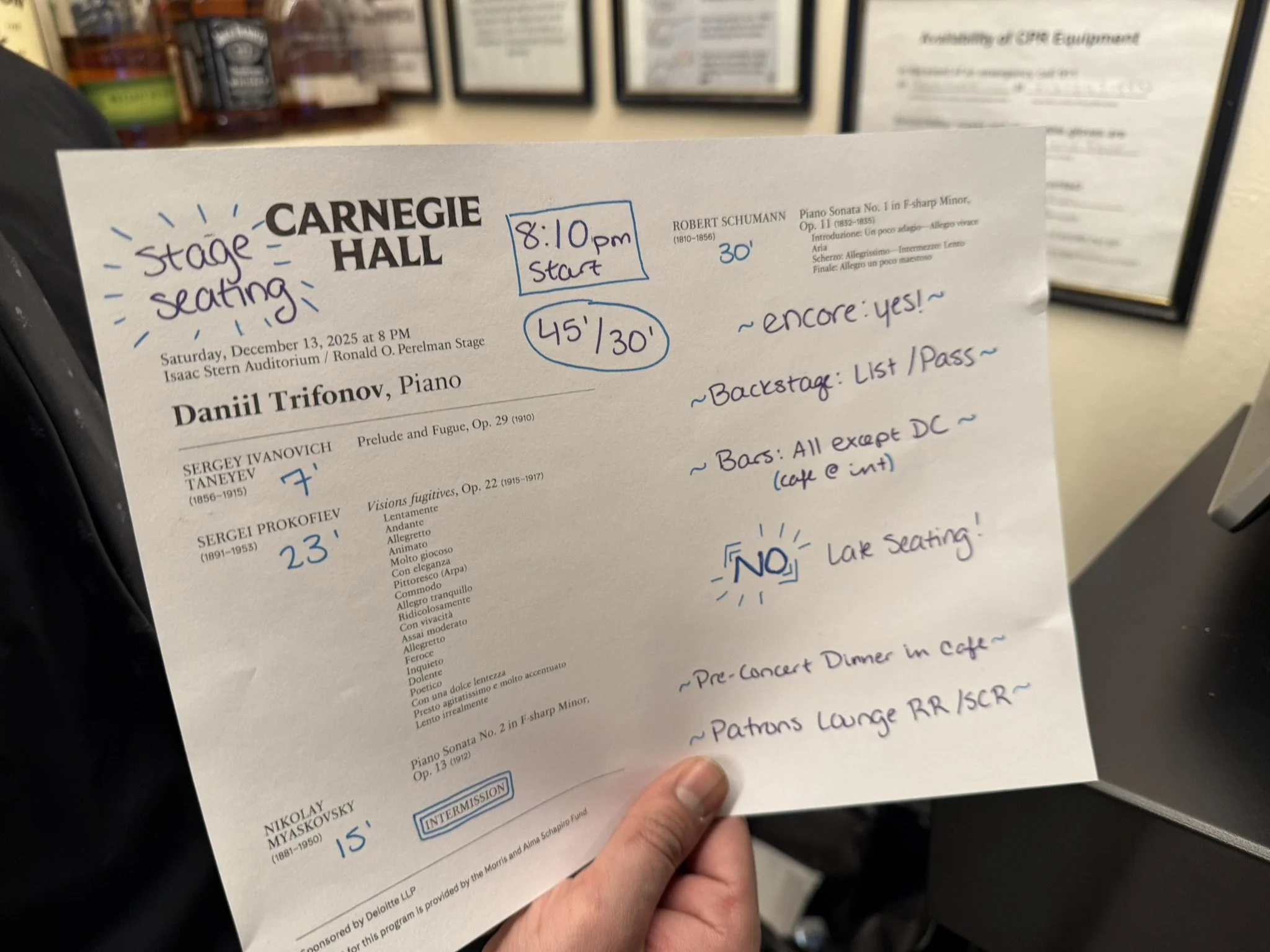

Daniil Trifonov, Piano, had a solo recital at Carnegie on 12.13.2025

TANEYEV Prelude and Fugue

PROKOFIEV Visions fugitives

MYASKOVSKY Piano Sonata No. 2

R. SCHUMANN Piano Sonata No. 1

Encores:

TCHAIKOVSKY "Little Red Riding Hood and Wolf" from Suite from The Sleeping Beauty (arr. Mikhail Pletenv)

TCHAIKOVSKY "Sweet Dreams" from Children's Album, Op. 39, No. 21

TCHAIKOVSKY "Lark Song" from Children's Album, Op. 39, No. 22

Taneyev’s Prelude and Fugue, Op. 29 is a work that fuses the rich musical language of the Russian Romantic school with contrapuntal techniques learned from Bach. Taneyev was a student of Tchaikovsky and Nikolai Rubinstein, and later taught Rachmaninoff and Scriabin. In the Prelude, flowing melodies and complex harmonic progressions convey profound emotion, combining lightness with serenity. The Fugue, on the other hand, demonstrates rigorous formal beauty through advanced counterpoint, with intertwining and developing themes that create both logical and musical tension for the listener. Rooted in a disciplined absorption of Western counterpoint rather than nationalism, this work exemplifies the depth and precision of polyphonic music appropriate to the 20th century, achieving a high level in both technique and expression.

Trifonov emphasizes clarity and the inner voice in his performance of this work. In the Prelude, he unfolds the music with restrained lyricism, allowing rhapsodic gestures to arc. The Fugue is transparent, with intertwining chromatic lines that bring Taneyev’s modern polyphony into sharp relief. When the Prelude’s theme returns at the climax, an inner tension fused with joy emerges, revealing a breath of 20th-century Russian music that transcends the Baroque.

Sergei Prokofiev’s Visions fugitives, Op. 22 (1915–1917) is a set of twenty short pieces composed during a period of political turmoil, in which he withdrew to his home to capture fleeting “visions” in music. The world of these miniatures combines the lightness of Impressionism, sharp harmonies and chromaticism, and Prokofiev’s characteristic incisive humor and detachment. Many of these pieces were performed by Prokofiev as encores in recitals. Trifonov, leaning close to the keyboard, imbued each piece with a unique delicacy. It was a new calling card from an artist exquisitely sensitive to nuance.

Nikolai Myaskovsky’s Piano Sonata is a profound work in a single-movement form. Incorporating the medieval Dies irae motif, it creates a solemn, somber atmosphere throughout. Its dense harmonies and technically demanding passages merge rhythmic drama with explorations of tonal fantasy, requiring both technical skill and intense concentration. In contrast to Prokofiev’s Visions fugitives, it presents a sound world filled with inner tension and shadow, balancing symphonic scale with introspection. Trifonov depicts the dense textures, recurring shadows, and soaring climaxes with masterful pacing and rich tonal color. Even the most violent passages retain a controlled expressiveness, and quotations of the Dies irae are seamlessly integrated into the musical structure. Streams of scales and octave passages are executed with precision, conveying the sonata’s inner conflicts and continuous narrative. Like Prokofiev, Myaskovsky studied under Rimsky-Korsakov and embodies both Russian modernism and tradition.

Robert Schumann’s Piano Sonata No. 1, Op. 11, composed between 1832 and 1835 during the early stages of his relationship with Clara Wieck, interweaves the contrasting characters of Florestan and Eusebius. Lively Allegro vivace passages, dreamy arias, dance-like scherzos, and a free-spirited finale convey the emotions of romance, blending improvisation and poetry—the quintessential Romantic piano music.

Schumann’s works were highly regarded in Russia, serving as models of inner expression and psychological depiction for composers such as Taneyev and Myaskovsky in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Schumann’s sonatas and miniatures frequently appeared in piano recital programs organized by the Moscow Conservatory and the St. Petersburg Musical Society, becoming study material for young pianists and composers. Newspapers and critics placed him alongside Liszt and Chopin, and his works were popular in concert settings.

Persistent rhythmic motifs clash with expansive lyrical movements, unsettling inner balance. In the first movement, Trifonov accumulates nervous energy without exploding it; in the aria, he delivers focused cantabile; the third-movement scherzo is agile and sharp; the finale integrates diverse episodes.

Three encores were performed. David Wright’s review notes, “Responding to the audience’s long and hearty applause, Trifonov played three short encores. While he bowed politely to the fans in the hall and on stage, his frustration during this portion was clearly palpable.”

Whether or not to perform encores is entirely the performer’s decision. Audience applause and cheers are expressions of gratitude and genuine emotion, not demands for additional performance. The audience cannot know if the performer is fatigued or uncomfortable with stage conventions.

He may be an introverted genius, most eloquent through the piano, and potentially finding public rituals distressing. This is understandable, but it is a personal matter, and it is not the audience’s responsibility to accommodate it. If he chooses not to play an encore, he has every right to return to the stage, bow, and leave. The freedom to conclude a performance lies solely with the performer.

The program itself was superb. The first half traced the development of Russian modern music, showing how it absorbed Western systems while cultivating its own national character. The second half combined these elements with Schumann, who had been received in Russia independently of Mozart or Beethoven. Schumann’s performance was astonishingly individual. His refined technique and acute live sensitivity were more than enough to move the audience deeply.

Audience applause, arising from genuine emotion, should be considered independently of the performer’s personal state or critics’ interpretations. In live performance, applause is not a matter of theory or etiquette but a spontaneous, physical reaction to having been touched by the music.

Team Sergey, a Trifonov enthusiast and friends

Pack to the end of the row Q on Balcony

Good job Sergey!

タネーエフの前奏曲とフーガ Op. 29は、ロシア・ロマン派の豊かな音楽語法とバッハに学んだ対位法を融合させた作品。タネーエフはチャイコフスキーとニコライ・ルービンシュタインの弟子であり、ラフマニノフやスクリャービンの師でもあった。前奏曲では流れるような旋律と複雑な和声進行によって深い情感が表現され、軽やかさと落ち着きを兼ね備えている。一方フーガでは高度な対位法により厳格な形式美が示され、旋律の交錯と展開が聴き手に論理的かつ音楽的な緊張感を与える。ナショナリズムよりも西洋の対位法を規律正しく吸収することに根ざした、20世紀初頭にふさわしい多声音楽の深みと精密さを追求し、技巧と表現の両面で完成度が高い。

トリフォノフはこの作品を明晰で内的な声を重視し、前奏曲は控えめな叙情で展開され、ラプソディックなジェスチャーがゆったりと弧を描く。フーガは透明で、半音階の旋律が絡み合う。タネーエフの現ポリフォニーが明瞭に浮かびあがる。前奏曲の主題が再び現れるクライマックスでは、内に広がる緊張と歓喜が融合し、バロックを越えた20世紀ロシアの新たな息吹が感じられた。

セルゲイ・プロコフィエフ:束の間の幻影 Op. 22 Visions fugitivesは、1915-1917年に作曲された20の短い小品集で、政治混乱を避け、自室にこもって音楽の「幻影」を記録した世界は、印象派の軽やかさ、鋭い和声・半音階、プロコフィエフ特有の冷徹でユーモラス。その多くはプロコフィエフがリサイタルでアンコールで演奏した。

トリフォノフは鍵盤に身をかがめ、それぞれの曲に独自の繊細な個性を吹き込んでいった。冒頭のレントメンテの謎めいた雰囲気から、第10曲リディコロサメンテのコミカルな玩具の行進曲、捉えどころのない終曲レント・イレアルメンテまで、すべてが彼ならではの表現だった。それは、ニュアンスに極めて敏感なアーティストによる、全く新しい名刺代わりの演奏だった。

ニコライ・ミャスコフスキーのピアノ・ソナタは、一楽章形式で書かれた深遠な作品。中世の「Dies irae」のモチーフが用いられ、全体に厳粛で陰鬱な雰囲気をもたらす。凝縮された密度の高い和声と技巧的なパッセージは、リズミカルで劇的な表現と幻想な調性探索が融合し、技巧と精神集中が要求される。プロコフィエフの束の間の幻影とは対照的に、内的な緊張と陰影に満ちた音の世界が展開され、交響曲のスケールと内省が共存している。トリフォノフは密度の高いテクスチャーと繰り返し現れる影や高揚するクライマックスを巧なテンポと豊かな色彩で描き出す。激しいパッセージも抑制された表現を保ち、「ディエス・イレ」の引用も音楽の構造に溶け込ませた。音階の急流やオクターブのパッセージは精緻に、ソナタの内面葛藤と連続する物語を明瞭に伝えていた。ミャスコフスキーはプロコフィエフと同じくリムスキー=コルサコフの弟子であり、ロシアのモダニズムと伝統を兼ね備えている。

1832年から1835年にかけて、クララ・ヴィークとの交際初期に生まれたロベルト・シューマン:ピアノ・ソナタ第1番 Op. 11。フロレスタンとオイゼビウスの人格、活発なアレグロ・ヴィヴァーチェ、夢想的なアリア、舞曲風のスケルツォ、自由奔放なフィナーレが織り交ざる恋愛感情を込めた作品で、即興と詩が共存するロマン派ピアノ音楽の典型。

シューマンの作品はロシアでも高く評価され、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて活躍したタネーエフやミャスコフスキーにとっても内面表現や心理描写の手本とされた。また、シューマンはモスクワ音楽院やサンクトペテルブルクの音楽協会主催の演奏会では、ピアノリサイタルのプログラムにソナタや小品が頻繁に組み込まれ、若手ピアニストや作曲家の練習・研究対象となっていた。新聞や批評でも、リストやショパンと並ぶ評価を受け、演奏会でも人気だった。

執拗なリズムのモチーフが壮大な叙情楽章と衝突し、内的均衡を揺さぶる。第1楽章は神経質な推進力を持ちながらも、トリフォノフはエネルギーを爆発させることなく蓄積させ、アリアでは集中力あるカンタービレが、スケルツォの第3楽章は敏捷で鋭い表現が、終楽章は多彩なエピソードを統合する。

アンコールは3曲演奏された。デビッド・ライトのレビューでは、「聴衆の長く大きな拍手に応え、トリフォノフは短いアンコールを3曲演奏した。客席と舞台上のファンに丁寧に頭を下げたものの、この部分に対する彼の苛立ちがはっきりと感じられた」と書かれていた。

アンコールを演奏するかどうかは、完全に演奏家自身の判断に委ねられている。聴衆からの拍手や歓声は、演奏に対する感謝と純粋な感動の表現であり、決してさらなる演奏を求める要求ではない。聴衆は、演奏家が疲れているのか、あるいは舞台上の慣習に不快感を抱いているのかを知ることはできない。

トリフォノフは内向的な天才なのかもしれない。ピアノを通して最も雄弁に自己表現し、公の儀式を苦痛に感じるタイプなのかもしれない。それは理解できる。しかし、それは個人的な問題であり、聴衆が察したり、配慮したりする責任ではない。もし彼がアンコールを演奏したくないのであれば、舞台に戻り、拍手に応え、お辞儀をして退場する権利は完全に彼にある。演奏を終える自由は、すべて彼自身にあるのだ。

プログラム自体は素晴らしかった。前半は、ロシア近代音楽が西洋の音楽体系を取り入れながら、独自の国民的な音楽性を培っていく過程を辿った。後半では、これらの要素がモーツァルトやベートーヴェンではなく、ロシアで独自に受容されたシューマンと組み合わされた。そして、シューマンの演奏は驚くほど個性的だった。トリフォノフの研ぎ澄まされた技巧と、鋭敏なライブ感は、聴衆を深く感動させるのに十分すぎるほどだった。

聴衆が純粋な感情から拍手をする自由は、演奏家の個人的な状況や批評家の解釈とは切り離して考えるべきだ。生演奏において、拍手は理論やマナーの問題ではなく、演奏に触れたことに対する身体的で自発的な反応なのである。