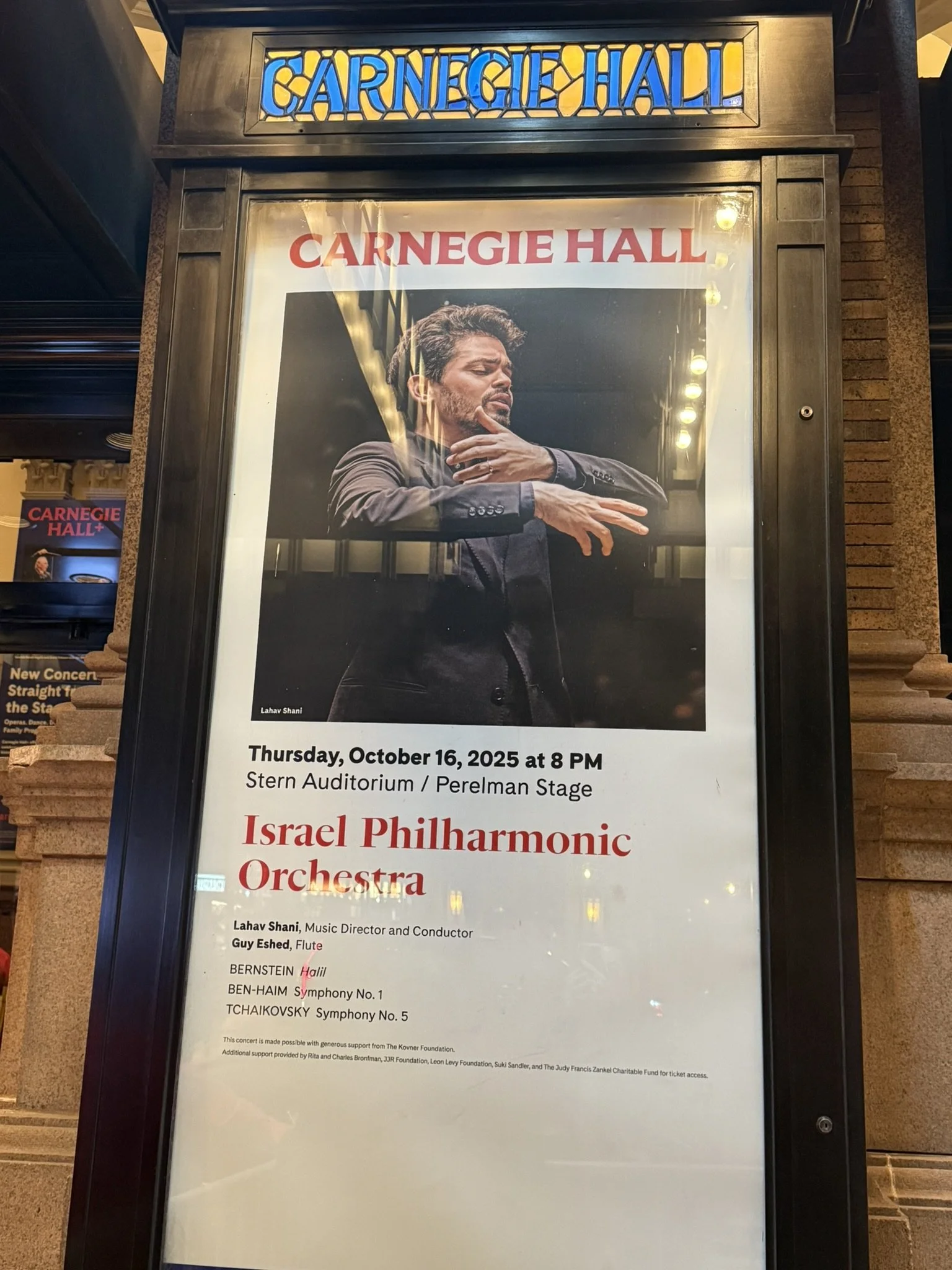

On October 16, the second night of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra and Lahav Shani at Carnegie Hall took place.

The first piece was Leonard Bernstein’s Halil (1981), written in memory of a 19-year-old flutist who lost his life in the war. Halil means “flute” in Hebrew.

The performance opened with a solo by principal flutist Guy Eshed. From the very first notes, an extremely faint, scraping sound became audible, leaving a slightly uncomfortable impression. The same phenomenon recurred at various points throughout the piece.

In the middle section, the music evoked Hindemith and Berg’s atonality, as well as postwar American classical idioms and even hints of Korngold’s lush harmonic world. Bernstein moves fluidly between tonal and atonal language, portraying threat and hope for life, love of art, and a prayer for peace.

At one point, the opening theme is taken up by flutes at the back of the stage and other instruments, as if the young flutist’s soul were echoing through the hall. This theme the shadow of consciousness in the production of La Sonnambula at Met Opera.

After the final non-vibrato long tone of the flute solo, the musicians remained still. I, too, offered a silent prayer to the spirit of Halil.

The second piece was Paul Ben-Haim’s Symphony No. 1.

Thirty years ago, I first heard Mahler with this orchestra. And now, I was hearing for the first time Ben-Haim Symphony—who inherited Mahler’s musical language and gave it a distinct Israeli voice. Written well before yesterday’s concerto, this work brims with fresh inspiration.

The opening bursts with destructive energy. The irregular rhythms in the cellos and lower strings instantly connect to Wagner—and made me long to hear Die Walküre performed by this orchestra someday.

Ben-Haim once told a singer from Yemen: “A melody doesn’t simply exist. You must create it yourself. Now it has become my language, shaped by my surroundings.” His First Symphony, I felt, is a direct reflection of the Palestine of his time. Structurally, it closely resembles Mahler, weaving military march figures with Yemeni prayer motifs and Oriental rhythms.

The second movement is simply beautiful. For a fleeting moment, it called to mind the Adagietto of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, yet it remained unmistakably Ben-Haim’s world—an oboe melody supported by harp, and strings that shrouded the sound like mist.

The third movement is a tarantella, reminiscent of Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony. Violist Dmitri Ratush unfolded a brief solo passage. He had also led the viola section yesterday, and together with the cellos, their rich, almost Wagnerian sound made me long even more to hear this orchestra in Wagner.

The second half featured Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5.

In 1888, Tchaikovsky was reportedly exhausted. The symphony begins with the clarinet’s mournful voice. Compared to yesterday’s Tchaikovsky, tonight’s performance was even more unmistakably Tchaikovskian, with a dragging, lingering weight.

In the middle of the third movement, as in Vienna under Muti, the orchestra seemed to wring out the recurring theme with raw intensity—mirroring how Tchaikovsky himself must have wrestled with it when he wrote the work.

From the Allegro vivace in the fourth movement, the tempo quickened and the sound thickened. Then, the brass entered in full force. Their boost never faltered, even through the relentless drive to the end.

10月16日、イスラエル・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団とラハフ・シャニによるカーネギーホール公演の2日目。1曲目は、バーンスタインが1981年に、19歳で戦争により命を落としたフルーティストのために書いた作品《ハリル(Halil)》だった。「ハリル」はヘブライ語で「フルート」を意味する。冒頭、首席フルート奏者ギィ・エシェドのソロから始まる。演奏が始まった瞬間、超かすかな何かが擦れるような音がして、少し不快に感じた。同じ現象は曲のさまざまな箇所でも耳に残った。途中には、ヒンデミットやベルクの無調、さらにはいわゆるアメリカ戦後のクラシック音楽の語法やコルンゴルトの響きを思わせる部分がある。バーンスタインはこの曲で、調性と無調のあいだを行き来しながら、脅威と生への希望、芸術への愛、そして平和への祈りを描いた。中盤、同じテーマが後方のフルートや他の楽器に受け継がれていくことで、この若きフルーティストの魂のこだまが響いているかのように感じられた。この作品のテーマは先月メトロポリタン歌劇場で観たアメリカ・オペラ《カバレリア&クレイ》の中にも見て取れた。フルートのテーマのこだまは《夢遊病の娘》の演出で見た、娘の意識の影を思いださせた。最後のソロフルートのノンビブラートのロングノートの後、彼らはじっと動かなかったので、私もハリルの魂に黙とうをささげた。

2曲目はベンハイムの交響曲1番だ。30年前にマーラーをこのオーケストラで初めて聴いた。そして、今、マーラーの語法を受け継いで、イスラエルの音楽を書いたベンハイムを初めて聴いた。昨日の協奏曲よりずっと前に書かれていて、ハイムのインスピレーションが新鮮だった。冒頭は破壊のエネルギー。チェロと低減の不規則なリズムはすぐにワーグナーに結び付く。いつかワルキューレをこのオーケストラで味わってみたくなる。ハイムはイエメン出身の歌手に「メロディーは実際にあるのではなく、自分で作り出すのです。今では、周囲の環境に影響を受けた私の言語となっている。」と語ったそうだ。ハイムの1番は、彼が見た当時のパレスチナその物だと思った。構成はマーラーとよく似ていて、ミリタリーマーチの音型に、イエメンの祈祷のテーマやオリエンタルなリズムが織り込まれている。2楽章はただ美しく、マーラー5番のアダージェットがすごく一瞬頭を過るが、やっぱりハイムの世界だった。オーボエのメロディにハープの伴奏。霧の様な弦楽器の音のまく。3楽章のタランテラ。メンデルスゾーンのイタリアによく似ている。ヴィオラのDmitri Ratushが短いソロパッセージを展開させる。昨日もビオラをリードしていたが、チェロと同じく、ワーグナーをこのオケでぜひ体験してみたくなる悪い音色だ。

後半はチャイコの5番。1888年にチャイコフスキーはとてもお疲れだったらしい。冒頭もクラリネットの嘆きから始まる。昨日のチャイコよりもより、チャイコらしく、ひきずるような後の残る演奏。3楽章、中間部。ウィーンもそうだったが、ムーティから揺さぶられて、同じテーマを振り絞る姿。チャイコが振り絞って書いた5番。4楽章のアベブレーベからテンポが上がり音の密度があがる。そして、いよいよブラスがドーンと登場。彼らのブーストはキリキリ演奏する終盤にも衰えなかった。