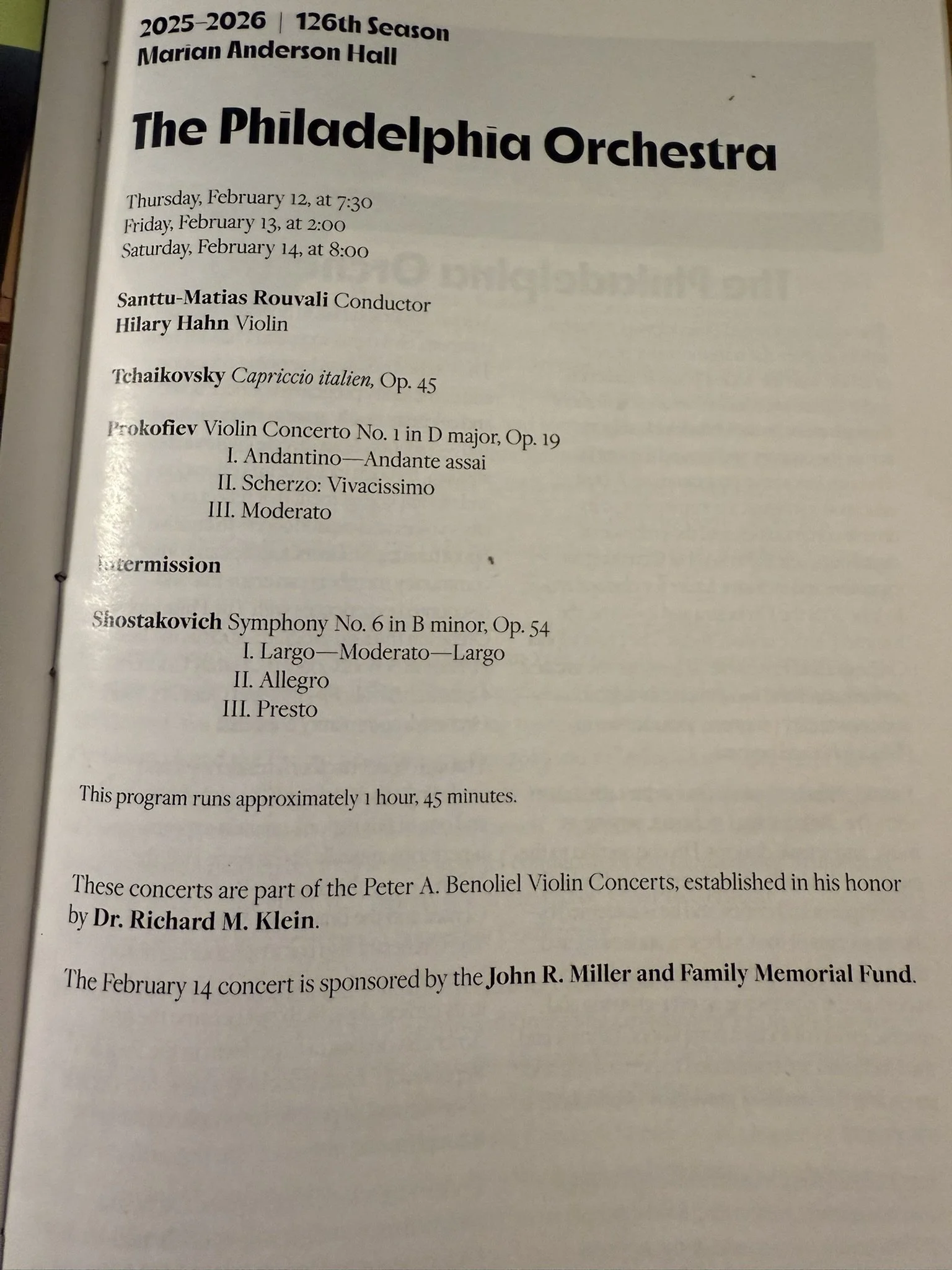

The shaggy-haired conductor Santtu-Matias Rouvali made his Philadelphia Orchestra debut. I attended the third performance on 2.14.2026. American violinist Hilary Hahn also made a long-awaited comeback. When Rouvali appeared on stage, he politely greeted concertmaster Kim, showing respect as a seasoned leader.

The first piece was Tchaikovsky’s Italian Capriccio, composed during his 1880 trip to Italy. It was a work by a man from a cold climate, inspired by the warm Mediterranean breezes, local scenery, and people. At this time, Tchaikovsky was free from the stresses of a troubled marriage, and the music lacked the inner tragedy or fervent, unrequited love that often characterizes his other works. The orchestra’s playing captured this light, dreamy quality, though at times the performers’ own sense of involvement felt intentionally raw. The audience members beside me were charmingly commenting to each other throughout, which added to the amusement.

The second piece was Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No. 1, composed in 1918 and premiered in Paris in 1923, with Hahn as the soloist. Due to a pinched nerve—a condition I also experience—Hahn canceled her planned 2024 performance of the Korngold Concerto with the Berlin Philharmonic and her upcoming recital with Lang Lang. I do not recall the last time I saw her, but her first album was released in 1997, which I bought and listened to immediately. I still have that album in Japan.

This was Hahn’s third performance in this program, and it felt like she was carefully gauging the acoustics of the venue and the audience, much like an F1 driver in a time trial. For the first encore, she played a contemporary solo piece I did not recognize—it was simply marvelous. Everyone stood and applauded, cheering, “Welcome back, Hilary!” The second encore was the Sarabande from Bach’s Partita No. 2. Apparently, this was the only performance across the three-day run in which she played two encores.

Hahn has consistently held the pole position among American violinists, earning countless accolades. Her music-making emphasizes faithful shaping of tone and sound rather than overt emotion, and the harmonics and rhythmic gestures highlight Prokofiev’s unique, straightforward character, unaffected by the political upheavals of post-revolutionary Russia. Rather than indulging in free interpretation, the performance clearly demonstrated her attention to musical structure and clarity. The orchestra’s principal members had rotated, resulting in a dreamy, mellow accompaniment reminiscent of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Different timbres, particularly the flute played by someone other than the virtuoso Geoffrey, offered fresh colors and charming idiosyncrasies.

In the second half, Rouvali conducted Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 6. The opening tutti recalled the sound of Sibelius or Wagner. Shostakovich’s signature irony was not strongly felt; playing the Philadelphia Orchestra in this manner gave the impression that each section was performing its own Shostakovich passage. Perhaps Rouvali aimed to draw out the rhythms and timbres without imposing a personal interpretation. The ensemble played with a freedom that suggested they had only just received the score. It was as if Shostakovich had carefully selected elements from other composers, and each section expressed these passages with its own flavor. While the polished performance I had heard with the Philharmonia at Carnegie Hall in the fall was fascinating, experiencing this raw, natural approach was uniquely rewarding.

The concert ended with thunderous applause. The Philadelphia audience is open, warm, and always engages with live music with respect and affection. I believe debuting performers, like the orchestra members, must feel fortunate. The audience member seated next to me has been familiar with the Philadelphia Orchestra since the days of Ormandy. It was truly an honor to share a seat with them and witness both Rouvali’s debut and Hahn’s comeback.

After listening to the program in its entirety, the first thing I realized was that Prokofiev is far freer, more original, and more eccentric than Shostakovich, who composed under the regime's watchful eye. His music may seem simple, repetitive, and straightforward, but even today it retains a remarkably distinctive character. Experiencing the three pieces in sequence revealed this not because of highly polished performances, but because each performer conveyed their genuine interests in a raw, natural way, all within the warmth of an attentive audience.

The Philadelphia Orchestra

Santtu-Matias Rouvali Conductor

Hilary Hahn Violin

Program

Tchaikovsky

Capriccio italien

Prokofiev

Violin Concerto No. 1

Shostakovich

Symphony No. 6

The shaggy-haired conductor Santtu-Matias Rouvali made his Philadelphia Orchestra debut. I attended the third performance on 2.14.2026. American violinist Hilary Hahn also made a long-awaited comeback. When Rouvali appeared on stage, he politely greeted concertmaster Kim, showing respect as a seasoned leader.

The first piece was Tchaikovsky’s Italian Capriccio, composed during his 1880 trip to Italy. It was a work by a man from a cold climate, inspired by the warm Mediterranean breezes, local scenery, and people. At this time, Tchaikovsky was free from the stresses of a troubled marriage, and the music lacked the inner tragedy or fervent, unrequited love that often characterizes his other works. The orchestra’s playing captured this light, dreamy quality, though at times the performers’ own sense of involvement felt intentionally raw. The audience members beside me were charmingly commenting to each other throughout, which added to the amusement.

The second piece was Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No. 1, composed in 1918 and premiered in Paris in 1923, with Hahn as the soloist. Due to a pinched nerve—a condition I also experience—Hahn canceled her planned 2024 performance of the Korngold Concerto with the Berlin Philharmonic and her upcoming recital with Lang Lang. I do not recall the last time I saw her, but her first album was released in 1997, which I bought and listened to immediately. I still have that album in Japan.

This was Hahn’s third performance in this program, and it felt like she was carefully gauging the acoustics of the venue and the audience, much like an F1 driver in a time trial. For the first encore, she played a contemporary solo piece I did not recognize—it was simply marvelous. Everyone stood and applauded, cheering, “Welcome back, Hilary!” The second encore was the Sarabande from Bach’s Partita No. 2. Apparently, this was the only performance across the three-day run in which she played two encores.

Hahn has consistently held the pole position among American violinists, earning countless accolades. Her music-making emphasizes faithful shaping of tone and sound rather than overt emotion, and the harmonics and rhythmic gestures highlight Prokofiev’s unique, straightforward character, unaffected by the political upheavals of post-revolutionary Russia. Rather than indulging in free interpretation, the performance clearly demonstrated her attention to musical structure and clarity. The orchestra’s principal members had rotated, resulting in a dreamy, mellow accompaniment reminiscent of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Different timbres, particularly the flute played by someone other than the virtuoso Geoffrey, offered fresh colors and charming idiosyncrasies.

In the second half, Rouvali conducted Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 6. The opening tutti recalled the sound of Sibelius or Wagner. Shostakovich’s signature irony was not strongly felt; playing the Philadelphia Orchestra in this manner gave the impression that each section was performing its own Shostakovich passage. Perhaps Rouvali aimed to draw out the rhythms and timbres without imposing a personal interpretation. The ensemble played with a freedom that suggested they had only just received the score. It was as if Shostakovich had carefully selected elements from other composers, and each section expressed these passages with its own flavor. While the polished performance I had heard with the Philharmonia at Carnegie Hall in the fall was fascinating, experiencing this raw, natural approach was uniquely rewarding.

The concert ended with thunderous applause. The Philadelphia audience is open, warm, and always engages with live music with respect and affection. I believe debuting performers, like the orchestra members, must feel fortunate. The audience member seated next to me has been familiar with the Philadelphia Orchestra since the days of Ormandy. It was truly an honor to share a seat with them and witness both Rouvali’s debut and Hahn’s comeback.

After listening to the program in its entirety, the first thing I realized was that Prokofiev is far freer, more original, and more eccentric than Shostakovich, who composed under the regime's watchful eye. His music may seem simple, repetitive, and straightforward, but even today it retains a remarkably distinctive character. Experiencing the three pieces in sequence revealed this not because of highly polished performances, but because each performer conveyed their genuine interests in a raw, natural way, all within the warmth of an attentive audience.

フィラデルフィア管弦楽団に指揮者でもじゃもじゃ頭のサントゥ=マティアス・ローヴァリ、Santtu‑Matias Rouvaliがデビューした。私は3回目の2月14日に聴きに行った。そして、アメリカのバイオリニスト、ヒラリー・ハーンも久々に復活した。ローヴァリがステージに現れると、先輩に胸を借りるように、コンサートマスターのキムに丁寧にあいさつしていた。一曲目はイタリア奇想曲。チャイコフスキーが1880年にイタリア旅行した時に書いた曲だ。寒い土地の人が温かい地中海の風や土地の風土や人を感じて書いた曲だ。この頃のチャイコフスキーは地獄の結婚生活など、ストレスから解放され、内から湧き出る悲壮感や誰かに片思いの熱々のロマンスを感じない、とんでもなく白々しい曲で、演奏する方々も気持ちの入れ方が中途半端で生々しくて面白かった。隣の客もすごくチャーミングに文句を仲間と言い合っていて面白かった。

2曲目のプロコフィエフのバイオリン協奏曲は1918年に20代の時に作曲され、1923年にパリで初演された。ソロをハーンが弾いた。ハーンは、私も患っている神経圧迫で2024年のベルリン・フィルとのコルンゴルトの協奏曲をキャンセルし、今シーズン予定されていたラン・ランとの公演もキャンセル。前回見たのは覚えていないが、彼女のファーストアルバムは1997年に発売され、当時、早速買って聴いていた。今でも日本の実家にある。この公演は3回目だが、F1のタイムトライアルのようにじっくりべニューと聴衆の感触を確かめるような演奏だった。アンコールに知らない現代曲をソロで演奏してくれた。すばらしい演奏だった。みんな総立ちでヒラリーおかえり拍手喝采。そして2曲目のアンコールはバッハのパルティータからサラバンドを演奏した。3日間の同じプログラムで、今回だけ2曲アンコールを演奏したそうである。ハーンはアメリカのバイオリニストではポールポジションを取り続けてきて、優勝を重ねてきたようなバイオリニストだ。実態のある、感情よりも音の形や音色を忠実に重ねて音楽を形作り、そのハーモニクスやリズムの動きがプロコフィエフのロシア革命後の影響を受けていない独特の素直な個性を引き立てている。自由な解釈よりも、彼がアメリカやパリで就職活動を行うポートフォリオとしての特徴をよく示した演奏だった。オーケストラの首席メンバーも入れ替わっていて、とてもドリーミーで、ディズニーの白雪姫や七人の小人などのファンタジーを思わせるメロウなオケの伴奏だった。違う音色、特にフルートが名手ジェフリーでない方で、違う音色やくせを楽しんだ。

後半はローヴァリがショスタコーヴィチの交響曲6番を振った。この曲は、ショスタコが体制下で、一見聴衆受けするように書かれ、実は抑圧や恐怖などを歌った曲だ。冒頭のトゥッティはシベリウスかワーグナーのようだった。ショスタコ独特の皮肉をあまり感じなかった。解釈を入れずフィラデルフィアを鳴らすと、それぞれのセクションが自分たちのショスタコを演奏しているような、ローヴァリは解釈を入れずリズムや音色を引き出していたのかもしれない。アンサンブルはまるで今日楽譜をもらったかのようにずっと自由だった。まるでショスタコーヴィチがどの作曲家のどの曲からその部分を取り出したかがわかるようで、それぞれのセクションがそれぞれの味付けで演奏しているように聴こえた。秋にカーネギーで聴いたフィルハーモニアとのよく仕上がった演奏も面白かったが、今回の様に、限りなく生の状態でお互い知り合うのは、恰好をつけない自然児の指揮者ならではだ。

終わるとまた盛大な拍手大喝采で、フィリーの聴衆はオープンで温かく、どんな時もこのライブの機会を敬意と愛情で楽しんでいる。オーケストラもそうだが、デビューした演奏家はとても幸せだと思う。隣のお客さんはオーマンディの頃からフィラデルフィア管弦楽団に親しんでいるそうだ。そんな方と席を並べられて、ローヴァリのデビューとハーンの復活に立ち会えたことは光栄なことだと心から思う。

最後まで聴いて一番初めに思ったのは、プロコフィエフは、体制を気にして作曲されたショスタコよりもずっと自由で独特で変態だということに気が付く。単純で単調でシンプルそうだが、今の感覚と照らし合わせてもかなり独特だ。3曲並べて聴いてそのことに気が付くのは、高度に仕上がった演奏よりも、このような生々しい彼らのそれぞれの興味が示され、しかもこの暖かな聴衆の中で体験できたからだと思う。